Abdul Reza Pahlavi

- Kamyar Pahlavi

- Sarvenaz Pahlavi

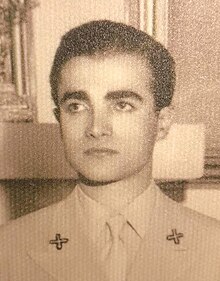

Abdul Reza Pahlavi (Persian: عبدالرضا پهلوی; 19 August 1924 – 11 May 2004) was a member of Iran's Pahlavi dynasty. He was a son of Reza Shah and a half-brother of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Early life and education

Abdul Reza Pahlavi was born on 19 August 1924 in Tehran.[1] His parents were Reza Pahlavi and Princess Esmat Dowlatshahi, the daughter of Prince Mojalal-e Dowleh Dowlatshahi Qajar.[2] She was a member of the Qajar dynasty[2] and the fourth as well as last wife of Reza Pahlavi.[3] They married in 1923.[1] Abdul Reza had three brothers and a sister: Ahmad Reza, Mahmoud Reza, Fatemeh and Hamid Reza Pahlavi.[4] They lived in the Marble palace in Tehran with their parents.[3] During his father's exile he accompanied him in Mauritius and then in Johannesburg, South Africa, from 1941 to 1944. During this period there were rumors that the Allies had been planning to install Abdul Reza as king instead of his elder brother Mohammad Reza.[1]

He studied business administration at Harvard University.[5]

Career and views

During the reign of his half-brother, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Abdul Reza headed different institutions. He was one of the prominent members of the royal court.[6] On 3 September 1949 he was named honorary head of the supreme planning board of Iran's seven-year plan.[7] Following the overthrow of the cabinet of Mohammad Mosaddegh in August 1953 there were proposals to depose the Shah Mohammad and to replace him with Abdul Reza in the post.[8]

Abdul Reza was the head of the planning organization between 1954 and 1955.[7] He served as the chairman of the Harvard-affiliated Iran centre for management studies from 1969 to 1979.[7] He also headed the wildlife conservation high council and international council for game and wildlife conservation. He was also part of the Royal Council that ruled Iran during the international visits of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[7] Following the assassination of a court minister by the Fada'iyan-e Islam in 1949, he suggested that the Shah should crush religious elements as did Reza Shah.[9] He argued that this assassination could be used as a legitimate reason for the adoptation of their father's iron fist policy against them.[9] He also believed that such a strategy is a must for the development of Iran.[9] Prince Abdul Reza was one of the critics of the Shah in the late 1950s.[10]

Abdul Reza also dealt with business, being wholly or partly the owner of factories, mining operations and agricultural firms.[11] In addition, he dealt with environmental affairs during that time.[12] He left Iran before the 1979 revolution together with other relatives.[11]

Hunting and wildlife conservation

Pahlavi was an enthusiastic hunter and sportsman throughout his life.[13][14] He was the founder and president of the International Foundation for the Conservation of Game (IGF) in Paris, a group promoting wildlife conservation and responsible hunting in developing countries.[15]

Pahlavi assisted in the creation of Iran's first game laws and game enforcement agency, and helped establish more than 20 million acres of reserves and parks in Iran. While criticized for promoting trophy hunting for himself and friends, Pahlavi aggressively pursued poachers while head of the Iranian Dept. of the Environment, establishing one of the most extensive and successful big-game management programs in the developing world.[16] He was also responsible for enacting law protecting endangered species such as the gazelle, Caspian tiger, wild ass, cheetah, and the Persian fallow deer from extinction, imposing stiff fines for game law violators.[17] In 1978, he approved the transfer of four Persian fallow deer from Iran to Israel before the fall of the Shah.[18] According to a survey by an Iranian environmentalist, Hoshang Zeaee, overhunting and environmental destruction since 1978 has resulted in the extinction of several species once native to the Iranian plateau, including the Jebeer Gazelle (Gazella Dorcas Fuscifrons), Persian Wild Ass (Equus Hermionus), Alborz Red Sheep (Ovis Ammon Orientaliss), Asian Cheetah (Acinonyx Jubatus), Persian Fallow Deer (Dama Mesopotamica) and Goitered Gazelle (Gazella Subgutturosia).[19]

Awards for hunting

Pahlavi was the recipient of several awards for his hunting-related activities. He was awarded the Weatherby Award in 1962.[18][20] In 1984 the Safari Club International honored him with the Hunting Hall of Fame and in 1988 he received the International Hunting Award.[18]

Personal life

Pahlavi married Pari Sima Pahlavi (née Zand) in Tehran on 12 October 1950.[21][22] He had two children from this marriage: Kamyar (born 1952) and Sarvenaz Pahlavi (born 1955). His family resided in Florida, the US, and in Paris, France.[18][23]

Death

Abdul Reza Pahlavi died in Florida on 11 May 2004.[1]

Honours

In addition to national honours, i.e., Grand Cross of the Order of Pahlavi, Pahlavi is the recipient of several foreign honours, including:

Knight Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (28 February 1949)

Knight Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance (28 February 1949) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (15 December 1974)

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (15 December 1974) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Supreme Sun (First Class)[citation needed]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Supreme Sun (First Class)[citation needed] Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim (24 November 1970)[citation needed]

Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim (24 November 1970)[citation needed] Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Isabella the Catholic (9 February 1978)[24]

Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Isabella the Catholic (9 February 1978)[24]

References

- ^ a b c d Gholam Reza Afkhami (2008). The Life and Times of the Shah. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA; London: University of California Press. pp. 77, 605. ISBN 978-0-520-94216-5.

- ^ a b "The Qajars (Kadjars) and the Pahlavis". Qajar Pages. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b Diana Childress (2011). Equal Rights Is Our Minimum Demand: The Women's Rights Movement in Iran, 2005. Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7613-7273-8.

- ^ Cyrus Ghani (2001). Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power. London; New York: I.B. Tauris. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-86064-629-4.

- ^ Ali Akbar Dareini (1998). The Rise and Fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty: Memoirs of Former General Hussein Fardust. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publication. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-208-1642-8.

- ^ Fakhreddin Azimi (2009). Quest for democracy in Iran: a century of struggle against authoritarian rule. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-674-02036-8.

- ^ a b c d "Developments of the Quarter: Comment and Chronology". The Middle East Journal. 4 (1): 83–93. January 1950. JSTOR 4322139.

- ^ Ali Massoud Ansari (1998). Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the myth of imperial authority (PhD thesis). SOAS University of London. p. 175. doi:10.25501/SOAS.00028497.

- ^ a b c Aaron Vahid Sealy (2011). "In their place": Marking and unmarking Shi'ism in Pahlavi Iran (PhD thesis). University of Michigan. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-124-92027-6. ProQuest 896366090.

- ^ Arash Norouzi (13 December 2017). ""Lack of Progress" Threatens Shah". Mohammad Mosaddegh Website.

Citing a secret NCS briefing report

- ^ a b "105 Iranian firms said controlled by royal family". The Leader Post. Tehran. AP. 22 January 1979.

- ^ Edgar Burke Inlow (1979). Shahanshah: The Study of Monarchy of Iran. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 91. ISBN 978-81-208-2292-4.

- ^ Craig Boddington (22 August 2012). "Who Was the World's Greatest Hunter?". Hunting. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Charles Levinson (1 February 2010). "How Bambi Met James Bond to Save Israel's 'Extinct' Deer". The Wall Street Journal. Jerusalem.

- ^ His Imperial Higness Prince Abdorreza Pahlavi AfricaHunting.com. Retrieved 30 May 2016

- ^ Iranian Revolution Stifles Big Game Hunting, The Pantagraph, 8 August 1979, Bloomington, Illinois p. 15

- ^ Ecology Falls Prey To Iranian Revolt, The Milwaukee Journal, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 16 May 1980

- ^ a b c d Michael Sand (16 October 2020). "Han Gjorde an Forskel". NetNatur (in Danish). Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Peyman Saloumeh. (Sept. 2005) Environment-Iran: Turning Ancient Forests Into Deserts IPS. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "Previous Winners/ Presenters of the Weatherby Award". Weatherby Foundation. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Augustus Mayhew. "Palm Beach Real Estate Roulette". New York Social Diary. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "Palm Beach Biltmore". Wikimapia. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Darrell Hofheinz (9 June 2015). "Palm Beach Biltmore penthouse fetches $7.4M". Palm Beach Daily News. Palm Beach. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Real Decreto 460/1978, de 9 de febrero, por el el que se concede la Gran Cruz de la Orden de Isabel la Católica a S. A. R. I. el Príncipe Abdur Reza" (PDF) (in Spanish). Boletín Oficial del Estado. 15 March 1978. p. 6160. Retrieved 17 December 2023.