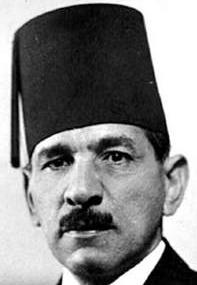

Aly Maher Pasha | |

|---|---|

علي ماهر باشا | |

| |

| 23rd Prime Minister of Egypt | |

| In office 23 July 1952 – 7 September 1952 | |

| Monarchs | Farouk Fuad II |

| Preceded by | Ahmad Najib al-Hilali |

| Succeeded by | Mohamed Naguib |

| In office 27 January 1952 – 2 March 1952 | |

| Monarch | Farouk |

| Preceded by | Mustafa el-Nahhas Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmad Najib al-Hilali |

| In office 18 August 1939 – 28 June 1940 | |

| Monarch | Farouk |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Mahmoud Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Hassan Sabry Pasha |

| In office 30 January 1936 – 9 May 1936 | |

| Monarchs | Fuad I Farouk |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Tawfiq Nasim Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Mustafa el-Nahhas Pasha |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 November 1882 Cairo, Khedivate of Egypt |

| Died | 25 August 1960 (aged 77) Geneva, Switzerland |

| Political party | Ittihad Party |

Aly Maher Pasha (Arabic: علي ماهر باشا; 9 November 1882[1] – 25 August 1960)[2] was an Egyptian political figure during the parliamentary era. He was the brother of Ahmad Maher and the great-uncle to Ali Maher El Sayed.

A lawyer, he joined the Wafd Party in 1919 and was a member of the delegation that negotiated with the Milner Commission.[3] Maher joined the Wafd after its first split, standing by alongside Mustafa al-Nahhas.[4] Though he reached the Central Committee of the Wafd, he ultimately left in 1921.[5] He was a member of the 1922 Constitutional Commission, which drafted the 1923 Egyptian Constitution.[3] He was elected to parliament as an independent in 1924, but later joined the conservative royalist Ittihad Party in 1925, becoming its vice president.[6]

He was the under-secretary of the minister of education in 1924 and later the minister of education from 1925 to 1926, minister of finance (1928-1929) and education and justice (1930-1932).[3][5] Maher was a royalist, seeking to improve the reputation of the king in Egyptian society. Around this time he was also office director for King Fuad in 1935 and later King Farouk in 1937, as well as a member of the regency council.[3] During his first ministry (January to May 1936), he sought to use Islam as a weapon against the Wafd, portraying the new King Farouk as a religious man.[7] However, Maher's politics were still fundamentally secular, believing that Islam should serve the monarchy, not the other way around.[8] Maher also represented Egypt during the St James Conference, trying to broker an agreement between the Zionists and Palestinians.[9]

His second ministry oversaw the beginning of World War II. He refused to issue a declaration of war against Nazi Germany, arguing that the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty did not technically require one. In a heated conversation with the British ambassador Sir Miles Lampson, he declared that:

if Egypt had sufficient troops to affect the course of the war, he would not have hesitated to declare war against Italy and Germany, but unfortunately Egypt had on her frontier only 5,000 men inadequately provided with transport. A declaration of war would, therefore, only be a spectacular gesture, causing ruin to 16 million inhabitants.[10]

Eventually, his government was dismissed, and was later arrested in April 1942 after creating a secret conservative Officers' Organization.[11] He would later become prime minister again in 1952 following Black Saturday, though his government was quickly dismissed by the king after refusing the issue an Interior Ministry report implicating the Wafd for handling Black Saturday.[12] Mahir was later chosen to form a ministry after the 1952 Egyptian Revolution, but was dismissed again after classes with the Revolutionary Command Council regarding land redistribution.

References

[edit]- ^ "علي ماهر باشا.. "عراب" الملك فؤاد الأول". 25 August 2017.

- ^ Mardelli, Bassil A. (April 2010). Middle East Perspectives: Personal Recollections (1947 - 1967). ISBN 9781450211161 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Goldschmidt 2023, p. 248.

- ^ Quraishi, Zaheer Masood (1967). Liberal Nationalism In Egypt: Rise and Fall of the Wafd Party. The Jamal Printing Press. p. 67.

- ^ a b Long 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Deeb, Marius (1979). Party Politics in Egypt: the Wafd & its Rivals 1919-1939. Ithaca Press London. p. 187.

- ^ Tripp 2022, p. 355.

- ^ Tripp 2022, p. 366"It was, after all, his intention that Islamic themes, symbols, authorities and organisations, both traditional and new, should all serve the king and, through the king, the cause of Palace policy – a policy directed by Ali Mahir alone"

- ^ Jankowski, James (October 1981). "The Government of Egypt and the Palestine Question, 1936-1939". Middle Eastern Studies. 17 (4): 440.

Its role was more that of the honest broker than of the committed participant, with Ali Mahir in particular attempting to hold out something to both Zionists and Palestinian Arabs in order to arrive at a zone of agreement.

- ^ Morewood, Steven (2005). The British Defence of Egypt 1935–1940: Conflict and crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean. Routledge. p. 176.

- ^ Tripp 1993, p. 65.

- ^ Gordon, Joel (1992). Nasser's Blessed Movement: Egypt's Free Officers and the July Revolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–34.

Sources

[edit]Goldschmidt, Arthur (2023). "Mahir, Ali". Historical Dictionary of Egypt (5th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 248. ISBN 9781538157350.

Tripp, Charles (2022). "Al-malik al-salih – Islam and the monarchy in 1930s Egypt". Middle Eastern Studies. 58 (3). Informa UK Limited: 354–370. doi:10.1080/00263206.2022.2047659. Retrieved 23 August 2025.

Long, Richard (2005). "Appendix 2: Egyptian personalities". British Pro-Consuls in Egypt, 1914-1929 : The Challenge of Nationalism. RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 186–187.

Tripp, Charles (1993). "Ali Mahir and the politics of the Egyptian army, 1936–1942". Contemporary Egypt: Through Egyptian Eyes. Routledge.

External links

[edit]