Leeds Tiger

The Leeds Tiger, 2021 | |

| Species | Bengal tiger |

|---|---|

| Sex | Probably male |

| Died | 1860 Deyrah Dhoon valley, near Dehradun, India |

| Cause of death | Shot by Charles Reid |

| Resting place | Mounted and displayed at Leeds City Museum, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England |

| Known for | Past mythical dangerous reputation; Present visitor attraction |

| Owner | Leeds City Council |

| Leeds City Museum | |

The Leeds Tiger is a taxidermy-mounted 19th-century Bengal tiger, displayed at Leeds City Museum in West Yorkshire, England. It has been a local visitor attraction for over 150 years.

The tiger was shot and killed by Charles Reid in the Dehrah Dhoon valley near Dehradun, India, in 1860. It was displayed as a tiger skin at the 1862 International Exhibition, and sold to William Gott, who had it mounted by Edwin Henry Ward, and presented it in 1863 to the museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England.

The Leeds Tiger's novelty and size drew public attention, as did the myths of a "dangerous reputation" which accumulated over the years. In 1979, Leeds City Museum curator Adrian Norris said, "The tiger has always been very popular with the public, and school parties in general".

Origins and acquisition

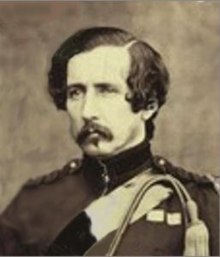

The Bengal tiger which ultimately became the mounted Leeds Tiger in Leeds City Museum originally inhabited the Deyrah Dhoon, near Dehradun; a valley near Mussoorie hill station in Uttarakhand, northern India. The animal was shot in March 1860 by Colonel Charles Reid (later General Sir Charles Reid, GCB) of the Sirmoor Battalion (2nd Gurkhas).[1] Reid was a sportsman who, on one 1872 afternoon in Elginshire, bagged 25.5 brace of grouse.[2] He wrote to a friend about the tiger kill:

I had a tiger ... which is now in the museum at Leeds, which was the largest tiger I ever killed or ever saw. As he lay on the ground he measured 12 feet 2 inches – his height I did not measure – from the tip of one ear to the tip of the other 191⁄2 inches. I never took skull measurements, nor did I ever weigh the tiger ... The three tigers mentioned are the largest I ever killed – all Dhoon tigers.[3][4]

M.B. Bose (1926) defends the published measurements of tiger kills by hunters such as Reid, and gives an explanation of the body lengths achieved by some Bengal tigers: "Length alone does not necessarily constitute fitness ... The elongated tiger is a result of the disease known to animal pathologists and zoologists as vertebromegaly in which the centra of the respective vertebrae become very much elongated and gothic in structure".[5] However the Madras Weekly Mail (1890) says that hunters such as Reid would measure tigers along the curves "from the nose over the head, down the neck and along the backbone" including the tail. "A naturalist measures tigers in a straight line" without the tail.[6]

In the 19th century the male pronoun was preferred for individuals in general, but in this case the masculinity of the tiger might have been obvious. Tiger testicles are visible, and male Bengal tigers can be almost twice as large as females.[7] Charles Reid's original measurements remain unverified; if verified the Leeds Tiger might originally have been one of the largest tigers on record.[8] Such kills were normally skinned and cured in India before being shipped back to London. This one was displayed in the 1862 International Exhibition,[3] while the specimen was still an unmounted tiger skin.[nb 1] As with cowhide and cowskin rugs, the cured and trimmed tiger pelt can be synonymous with the tiger rug, the only difference being whether it is displayed on the wall or floor.[nb 2] Since the specimen was cured as a hunting trophy skin or rug which would typically include the mounted head, it is possible that the head of the mounted Leeds Tiger still contains the skull and teeth of the original Bengal tiger shot in India.[10]: 33

After the exhibition, the skin was purchased by William Gott (1797–1863), the son of Benjamin Gott.[11][12] Gott commissioned Edwin Henry Ward (father of Rowland Ward) to mount it for the museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society.[13]

Display and mount

The mount was allocated an accession number in Leeds,[nb 3] and displayed in the Philosophical Hall on Park Row. Its label read, "Shot in Deyrah Dhoon in March 1860 by Colonel Charles Reid, C.B., H.M. 2nd Goorkahs (Sirmoor Rifles) by whom this tiger is exhibited".[14] The Leeds Tiger drew public attention. At the annual conversazione of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society in 1863, the Reverend Thomas Hincks stated that, "he was afraid that the tiger ... had been too much the great lion ... and that they had neglected many other noble beasts surrounding it".[15] In a long article extolling the philanthropy of William Gott, the Leeds Mercury reported, "The setting up of this tiger is so natural and so perfect in posture and anatomical detail, that it is certainly to be looked upon as a work of art quite as much as an object for scientific observation ... "[16] and in the same vein, "Professor Owen has more than once stated that it is the finest and largest animal of its species not only in England but in Europe".[12][13]

Additional material has been used to increase the area of the skin for mounting purposes.[17] Ebony Andrews (2009) suggests that the taxidermist Ward would have mounted the tiger skin to be viewed from above and laterally so that patching or the strange shape of the head might have remained unnoticed.[9] In 2016 the Leeds Tiger, together with several other natural history exhibits, was temporarily placed in frozen storage at Leeds Discovery Centre to destroy any infestation by the webbing clothes moth which had been detected in the gallery. The mount was returned to the museum after treatment.[18]

The museum in Leeds has been through many incarnations, but the Leeds Tiger has been on display through all of them, almost continuously for over 150 years.[19][20]

- Leeds Tiger in original glass case, c.1900

- Leeds Tiger display, 2021

- Additional material was added below the chin

Leeds Tiger myths

In a 1906 museum guidebook, the curator Henry Crowther wrote that the original Bengal tiger "destroyed forty bullocks in six weeks and was considered so formidable that no native dare venture into the jungle where this noble beast reigned supreme".[19][21] There does not seem to be any contemporary evidence for this but the myth was perpetuated by its 1950s label: "This magnificent man-eater was presented to the City Museum by William Gott. It had long terrorised the villagers and farmstock of a limited area, and besides accounting for several natives, no fewer than forty bullocks were killed during a period of six weeks".[14] In 2016, the story was revisited by the Yorkshire Evening Post which reported, "We'll never know for certain whether the Leeds Tiger really lived up to its dangerous reputation, but today it sends a shiver down the spines of visitors to Leeds City Museum".[21] In 2021 Leeds Museums & Galleries curator Clare Brown stated that there was no evidence "that it was anything other than a large tiger minding its own business in a quiet Himalayan valley on the day Charles Reid turned up and shot it".[22]

Paul Chrystal (2016) suggests that the Leeds Tiger was "saved from the curators' skip by The Yorkshire Post, when it mounted a successful campaign to retain it as a popular centrepiece of the museum's collection".[23] However the museum's curator Adrian Norris said in 1979,[10]

The tiger has always been very popular with the public, and school parties in general, and is one of the few items in the Museum we dare not remove, or cover, for fear of being swamped with complaints from members of the public, who in some cases have travelled many hundreds of miles just to see it.[10]

Mount designed for drama

- Foot

-

Eye

Eye - Stance

- Gape

Notes

- ^ Ebony Andrews (2009) describes the mounted tiger as strangely-shaped and over-sized due to its time as a rug.[9] It is true that the original Bengal tiger was described as "the largest I ever killed" by Reid but the tiger skin is not described as a rug in contemporary documents. After more than 150 years the mount is sagging, but it is the original mount by Ward, and the current shape is a recognisable part of the identity of the Leeds Tiger.

- ^ Trade in tiger skin rugs is now illegal. Traditionally the tiger skin rug was just the cured pelt with no additional material (except perhaps the mounting of the head), as can be seen here: "Trader sold 'extinct' tiger skin rugs on eBay". BBC News. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2021. Hence the original trimmed pelt of the Leeds Tiger has sometimes been referred to as a tiger skin rug.

- ^ Accession number is LEEDM.C.1862.29.13.

References

- ^ Tuker, Francis (1957). Gorkha: The Story of the Gurkhas of Nepal. London: Constable and Co. p. 92.

- ^ "The moors and forests: Elginshire". Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 30 August 1872. p. 3 col.e. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b Sterndale, Robert Armitage (1884). Natural history of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co. p. 593.

- ^ "The larger carnivora of India". Madras Weekly Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 31 July 1886. p. 9 col 4, 10 col a. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Bose, M.B. (22 April 1926). "Large tigers". Englishman's Overland Mail. British Newspaper Archive. p. 19 col.b. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "The measuring of tigers". Madras Weekly Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 14 May 1890. p. 436/14 col.a. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Cook, Maria (19 April 2018). "How to Tell a Female & Male Tiger Apart". sciencing.com. Sciencing. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Largest feline carnivore". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b Andrews, Ebony (2009). The Biographical Afterlife of the Leeds Tiger. Archives at Leeds Discovery Centre: University of Leeds, unpublished masters dissertation. p. 18.

- ^ a b c Andrews, Ebony Laura (2013). Interpreting Nature: Shifts in the Presentation and Display of Taxidermy in Contemporary Museums in Northern England (PDF) (Ph.D.). University of Leeds. p. 184. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Death of Wm Gott Esq". Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 29 August 1863. p. 5 col 2. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society : Professor Owen's inaugural address". Leeds Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 17 December 1862. p. 3 col 2. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b Anonymous (1862). "Forty-third report of the Council of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society". Reports of the Council of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 43: 9.

- ^ a b Norris, Adrian (1985). "Notes on the Natural History Collections in Leeds City Museum. Number 5: The Leeds Tiger". Leeds Naturalists' Club Newsletter. 2 (1): 19–20.

- ^ "Leeds Philosophical Society: the conversazione". Leeds Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 9 December 1863. p. 3 col 5. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Visit to the art exhibition in the Leeds Philosophical Hall no.IV". Leeds Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 2 January 1863. p. 4 col 1. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ The nature of the extra material used to convert the tiger skin to a full mount is unknown. It may be Victorian synthetic fur, or it may be parts of other tiger skins

- ^ ""Video: How they reclaimed Leeds' shabby tiger from the moths"". Yorkshire Post. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ a b Brears, Peter (1989). Of Curiosities & Rare Things: the story of Leeds City Museum. Leeds: The Friends of Leeds City Museum. ISBN 0-907588-077.

- ^ Roles, John (2014). Director's Choice. London: Scala Arts and Heritage Publishers Limited. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-85759-840-7.

- ^ a b "Leeds nostalgia: The story of the Leeds Tiger". Yorkshire Evening Post. JP Media. 31 December 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "The Tiger Who Came to Leeds". Leeds Museums & Galleries. 12 April 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ Chrystal, Paul (2016). Leeds in 50 Buildings: 9. Leeds City Museum 1819 Park Row. Leeds, England: Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445654553. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

External links

- Leeds City Council Communications team (13 January 2016). "Leeds Museums and Galleries object of the week - The Leeds Tiger". Leeds Museums and Galleries. Retrieved 27 June 2021.