List of Chinese discoveries

| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

|

| By subject

|

|

Aside from many original inventions, the Chinese were also early original pioneers in the discovery of natural phenomena which can be found in the human body, the environment of the world, and the immediate Solar System. They also discovered many concepts in mathematics. The list below contains discoveries which found their origins in China.

Discoveries

Ancient and imperial era

- Chinese remainder theorem: The Chinese remainder theorem, including simultaneous congruences in number theory, was first created in the 3rd century AD in the mathematical book Sunzi Suanjing posed the problem: "There is an unknown number of things, when divided by 3 it leaves 2, when divided by 5 it leaves 3, and when divided by 7 it leaves a remainder of 2. Find the number."[1] This method of calculation was used in calendrical mathematics by Tang dynasty (618–907) mathematicians such as Li Chunfeng (602–670) and Yi Xing (683–727) in order to determine the length of the "Great Epoch", the lapse of time between the conjunctions of the moon, sun, and Five Planets (those discerned by the naked eye).[1] Thus, it was strongly associated with the divination methods of the ancient Yijing.[1] Its use was lost for centuries until Qin Jiushao (c. 1202–1261) revived it in his Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections of 1247, providing constructive proof for it.[1]

- Circadian rhythm in humans: The observation of a circadian or diurnal process in humans is mentioned in Chinese medical texts dated to around the 13th century, including the Noon and Midnight Manual and the Mnemonic Rhyme to Aid in the Selection of Acu-points According to the Diurnal Cycle, the Day of the Month and the Season of the Year.[2]

- Decimal fractions: decimal fractions were used in Chinese mathematics by the 1st century AD, as evidenced by The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, while they appear in the works of Arabic mathematics by the 11th century (most likely independently of Chinese influence) and in European mathematics by the 12th century, although the decimal point was not used until the work of Francesco Pellos in 1492 and not clarified until the 1585 publication of Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin (1548–1620).[3]

- Diabetes, recognition and treatment of: The Huangdi Neijing compiled by the 2nd century BC during the Han dynasty identified diabetes as a disease suffered by those who had made an excessive habit of eating sweet and fatty foods, while the Old and New Tried and Tested Prescriptions written by the Tang dynasty physician Zhen Quan (died 643) was the first known book to mention an excess of sugar in the urine of diabetic patients.[4]

- Equal temperament: During the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), the music theorist and mathematician Jing Fang (78–37 BC) extended the 12 tones found in the 2nd century BC Huainanzi to 60.[6] While generating his 60-divisional tuning, he discovered that 53 just fifths is approximate to 31 octaves, calculating the difference at ; this was exactly the same value for 53 equal temperament calculated by the German mathematician Nicholas Mercator (c. 1620–1687) as 353/284, a value known as Mercator's Comma.[7][8] The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) music theorist Zhu Zaiyu (1536–1611) elaborated in three separate works beginning in 1584 the tuning system of equal temperament. In an unusual event in music theory's history, the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin (1548–1620) discovered the mathematical formula for equal temperament at roughly the same time, yet he did not publish his work and it remained unknown until 1884 (whereas the Harmonie Universelle written in 1636 by Marin Mersenne is considered the first publication in Europe outlining equal temperament); therefore, it is debatable who discovered equal temperament first, Zhu or Stevin.[9][10] In order to obtain equal intervals, Zhu divided the octave (each octave with a ratio of 1:2, which can also be expressed as 1:212/12) into twelve equal semitones while each length was divided by the 12th root of 2.[11] He did not simply divide the string into twelve equal parts (i.e. 11/12, 10/12, 9/12, etc.) since this would give unequal temperament; instead, he altered the ratio of each semitone by an equal amount (i.e. 1:2 11/12, 1:210/12, 1:29/12, etc.) and determined the exact length of the string by dividing it by 12√2 (same as 21/12).[11]

- Gaussian elimination: First published in the West by Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) in 1826, the algorithm for solving linear equations known as Gaussian elimination is named after this Hanoverian mathematician, yet it was first expressed as the Array Rule in the Chinese Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, written at most by 179 AD during the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) and commented on by the 3rd century mathematician Liu Hui.[12][13][14]

- Geomorphology: In his Dream Pool Essays of 1088, Shen Kuo (1031–1095) wrote about a landslide (near modern Yan'an) where petrified bamboos were discovered in a preserved state underground, in the dry northern climate zone of Shanbei, Shaanxi; Shen reasoned that since bamboo was known only to grow in damp and humid conditions, the climate of this northern region must have been different in the very distant past, postulating that climate change occurred over time.[15][16] Shen also advocated a hypothesis in line with geomorphology after he observed a stratum of marine fossils running in a horizontal span across a cliff of the Taihang Mountains, leading him to believe that it was once the location of an ancient shoreline that had shifted hundreds of km (mi) east over time (due to deposition of silt and other factors).[17][18]

- Greatest Common Divisor: Rudolff gave in his text Kunstliche Rechnung, 1526 the rule for finding the greatest common divisor of two integers, which is to divide the larger by the smaller. If there is a remainder, divide the former divisor by this, and so on;. This is just the Mutual Subtraction Algorithm as found in the Rule for Reduction of Fractions, Chapter 1, of The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art [19]

- Grid reference: Although professional map-making and use of the grid had existed in China before, the Chinese cartographer and geographer Pei Xiu of the Three Kingdoms period was the first to mention a plotted geometrical grid reference and graduated scale displayed on the surface of maps to gain greater accuracy in the estimated distance between different locations.[20][21][22] Historian Howard Nelson asserts that there is ample written evidence that Pei Xiu derived the idea of the grid reference from the map of Zhang Heng (78–139 CE), a polymath inventor and statesman of the Eastern Han dynasty.[23]

- Irrational Numbers: Although irrational numbers were first discovered by the Pythagorean Hippasus, the ancient Chinese never had the philosophical difficulties that the ancient Greeks had with irrational numbers such as the square root of 2. Simon Stevin (1548–1620) considered irrational numbers are numbers that can be continuously approximated by rationals. Li Hui in his comments on the Nine Chapters of Mathematical Art show he had the same understanding of irrationals. As early as the third century Liu knew how to get an approximation to an irrational with any required precision when extracting a square root, based on his comment on 'the Rule for Extracting the Square Root', and his comment on 'the Rule for Extracting the Cube Root'. The ancient Chinese did not differentiate between rational and irrational numbers, and simply calculated irrational numbers to the required degree of precision.[24]

- Jia Xian triangle: This triangle was the same as Pascal's Triangle, discovered by Jia Xian in the first half of the 11th century, about six centuries before Pascal. Jia Xian used it as a tool for extracting square and cubic roots. The original book by Jia Xian titled Shi Suo Suan Shu was lost; however, Jia's method was expounded in detail by Yang Hui, who explicitly acknowledged his source: "My method of finding square and cubic roots was based on the Jia Xian method in Shi Suo Suan Shu."[25] A page from the Yongle Encyclopedia preserved this historic fact.

- Leprosy, first description of its symptoms: The Feng zhen shi 封診式 (Models for sealing and investigating), written between 266 and 246 BC in the State of Qin during the Warring States period (403–221 BC), is the earliest known text which describes the symptoms of leprosy, termed under the generic word li 癘 (for skin disorders).[26] This text mentioned the destruction of the nasal septum in those suffering from leprosy (an observation that would not be made outside of China until the writings of Avicenna in the 11th century), and according to Katrina McLeod and Robin Yates it also stated lepers suffered from "swelling of the eyebrows, loss of hair, absorption of nasal cartilage, affliction of knees and elbows, difficult and hoarse respiration, as well as anaesthesia."[26] Leprosy was not described in the West until the writings of the Roman authors Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC – 37 AD) and Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD).[26] Although it is alleged that the Indian Sushruta Samhita, which describes leprosy,[27] is dated to the 6th century BC, India's earliest written script (besides the then long extinct Indus script)—the Brāhmī script—is thought to have been created no earlier than the 3rd century BC.[28]

- Li Shanlan identity: discovered by the mathematician Li Shanlan in 1867.[29]

- Liu Hui's π algorithm: Liu Hui's π algorithm was invented by Liu Hui (fl. 3rd century), a mathematician of Wei Kingdom.

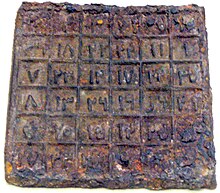

- Magic squares: The earliest magic square is the Lo Shu square, dating to 4th century BCE China. The square was viewed as mystical, and according to Chinese mythology, "was first seen by Emperor Yu."[30]

- Map scaling: The foundations for quantitative map scaling goes back to ancient China with textual evidence that the idea of map scaling was understood by the second century BC. Ancient Chinese surveyors and cartographers had ample technical resources used to produce maps such as counting rods, carpenter's square's, plumb lines, compasses for drawing circles, and sighting tubes for measuring inclination. Reference frames postulating a nascent coordinate system for identifying locations were hinted by ancient Chinese astronomers that divided the sky into various sectors or lunar lodges.[31] The Chinese cartographer and geographer Pei Xiu of the Three Kingdoms period created a set of large-area maps that were drawn to scale. He produced a set of principles that stressed the importance of consistent scaling, directional measurements, and adjustments in land measurements in the terrain that was being mapped.[31]

- Negative numbers, symbols for and use of: in the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art compiled during the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) by 179 AD and commented on by Liu Hui (fl. 3rd century) in 263,[3] negative numbers appear as rod numerals in a slanted position.[32] Negative numbers represented as black rods and positive numbers as red rods in the Chinese counting rods system perhaps existed as far back as the 2nd century BC during the Western Han, while it was an established practice in Chinese algebra during the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD).[33] Negative numbers denoted by a "+" sign also appear in the ancient Bakhshali manuscript of India, yet scholars disagree as to when it was compiled, giving a collective range of 200 to 600 AD.[34] Negative numbers were known in India certainly by about 630 AD, when the mathematician Brahmagupta (598–668) used them.[35] Negative numbers were first used in Europe by the Greek mathematician Diophantus (fl. 3rd century) in about 275 AD, yet were considered an absurd concept in Western mathematics until The Great Art written in 1545 by the Italian mathematician Girolamo Cardano (1501–1576).[35]

- Pi calculated as : The ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, Indians, and Greeks had long made approximations for π by the time the Chinese mathematician and astronomer Liu Xin (c. 46 BC–23 AD) improved the old Chinese approximation of simply 3 as π to 3.1547 as π (with evidence on vessels dating to the Wang Mang reign period, 9–23 AD, of other approximations of 3.1590, 3.1497, and 3.1679).[36][37] Next, Zhang Heng (78–139 AD) made two approximations for π, by proportioning the celestial circle to the diameter of the earth as = 3.1724 and using (after a long algorithm) the square root of 10, or 3.162.[37][38][39] In his commentary on the Han dynasty mathematical work The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, Liu Hui (fl. 3rd century) used various algorithms to render multiple approximations for pi at 3.142704, 3.1428, and 3.14159.[40] Finally, the mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi (429–500) approximated pi to an even greater degree of accuracy, rendering it , a value known in Chinese as Milü ("detailed ratio").[41] This was the best rational approximation for pi with a denominator of up to four digits; the next rational number is , which is the best rational approximation. Zu ultimately determined the value for π to be between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927.[42] Zu's approximation was the most accurate in the world, and would not be achieved elsewhere for another millennium,[43] until Madhava of Sangamagrama[44] and Jamshīd al-Kāshī[45] in the early 15th century.

- True north, concept of: The Song dynasty (960–1279) official Shen Kuo (1031–1095), alongside his colleague Wei Pu, improved the orifice width of the sighting tube to make nightly accurate records of the paths of the moon, stars, and planets in the night sky, for a continuum of five years.[46] By doing so, Shen fixed the outdated position of the pole star, which had shifted over the centuries since the time Zu Geng (fl. 5th century) had plotted it; this was due to the precession of the Earth's rotational axis.[47][48] When making the first known experiments with a magnetic compass, Shen Kuo wrote that the needle always pointed slightly east rather than due south, an angle he measured which is now known as magnetic declination, and wrote that the compass needle in fact pointed towards the magnetic north pole instead of true north (indicated by the current pole star); this was a critical step in the history of accurate navigation with a compass.[49][50][51]

Modern era

- Arteminisinin, anti-malarial treatment: The antimalarial drug of compound artemisinin found in Artemisia annua, the latter being a plant long used in traditional Chinese medicine, was discovered in 1972 by Chinese scientists in the People's Republic led by Tu Youyou and has been used to treat multi-drug resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum malaria.[52][53][54] Artemisinin remains the most effective treatment for malaria today and has saved millions of lives and is yielded one of the greatest drug discoveries in modern medicine.[55]

- Chen's theorem: Chen's theorem states that every sufficiently large even number can be written as the sum of either two primes, or a prime and a semiprime, and was first proven by Chen Jingrun in 1966,[56] with further details of the proof in 1973.[57]

- Chen prime: A prime number p is called a Chen prime if p + 2 is either a prime or a product of two primes (also called a semiprime). The even number 2p + 2 therefore satisfies Chen's theorem. The Chen primes are named after Chen Jingrun, who proved in 1966 that there are infinitely many such primes. This result would also follow from the truth of the twin prime conjecture.[58]

- Cheng's eigenvalue comparison theorem: Cheng's theorem was introduced in 1975 by Hong Kong mathematician Shiu-Yuen Cheng.[59] It states in general terms that when a domain is large, the first Dirichlet eigenvalue of its Laplace–Beltrami operator is small. This general characterization is not precise, in part because the notion of "size" of the domain must also account for its curvature.[60]

- Chern class: Chern classes are characteristic classes in mathematics first introduced by Shiing-Shen Chern in 1946.[61][a]

- Chow's moving lemma: In algebraic geometry, Chow's moving lemma, named after Wei-Liang Chow, states: given algebraic cycles Y, Z on a nonsingular quasi-projective variety X, there is another algebraic cycle Z' on X such that Z' is rationally equivalent to Z and Y and Z' intersect properly. The lemma is one of key ingredients in developing the intersection theory, as it is used to show the uniqueness of the theory.

- Culturing Chlamydia trachomatis bacteria: Chlamydia trachomatis agent was first cultured in the yolk sacs of eggs by Chinese scientists in 1957 [62]

- Feathered theropods: The first feathered dinosaur outside of Avialae, Sinosauropteryx, meaning "Chinese reptilian wing," was discovered in the Yixian Formation by Chinese paleontologists in 1996.[63] The discovery is seen as evidence that dinosaurs originated from birds, a theory proposed and supported decades earlier by paleontologists like Gerhard Heilmann and John Ostrom, but "no true dinosaur had been found exhibiting down or feathers until the Chinese specimen came to light."[64] The dinosaur was covered in what are dubbed 'protofeathers' and considered to be homologous with the more advanced feathers of birds,[65] although some scientists disagree with this assessment.[66]

- Finite element method: In numerical analysis, the finite element method is a technique for finding approximate solutions to systems of partial differential equations. The FEM was developed in the West by Alexander Hrennikoff and Richard Courant, and independently in China by Feng Kang.

- Grunwald–Wang theorem: In algebraic number theory, the Grunwald–Wang theorem states that—except in some precisely defined cases—an element x in a number field K is an nth power in K if it is an nth power in the completion for almost all (i.e. all but finitely many) primes of K. For example, a rational number is a square of a rational number if it is a square of a p-adic number for almost all primes p. The Grunwald–Wang theorem is an example of a local-global principle. It was introduced by Wilhelm Grunwald (1933), but there was a mistake in this original version that was found and corrected by Shianghao Wang (1948).

- Hua's identity: In algebra, Hua's identity[67] states that for any elements a, b in a division ring, : whenever . Replacing with gives another equivalent form of the identity: :

- Hua's lemma: In mathematics, Hua's lemma,[68] named for Hua Loo-keng, is an estimate for exponential sums.

- Heterosis in rice, three-line hybrid rice system: A team of agricultural scientists headed by Yuan Longping applied heterosis to rice, developing the three-line hybrid rice system in 1973.[69] The innovation allowed for roughly 12,000 kg (26,450 lbs) of rice to be grown per hectare (10,000 m2). Hybrid rice has proven to be greatly beneficial in areas where there is little arable land, and has been adopted by several Asian and African countries. Yuan won the 2004 Wolf Prize in agriculture for his work.[70]

- Huang-Minglon modification: The Huang-Minglon modification, introduced by Chinese chemist Huang Minlon,[71][72] is a modification of the Wolff–Kishner reduction and involves heating the carbonyl compound, potassium hydroxide, and hydrazine hydrate together in ethylene glycol in a one-pot reaction.[73]

- Ky Fan norms: The sum of the k largest singular values of M is a matrix norm, the Ky Fan k-norm of M. The first of the Ky Fan norms, the Ky Fan 1-norm is the same as the operator norm of M as a linear operator with respect to the Euclidean norms of Km and Kn. In other words, the Ky Fan 1-norm is the operator norm induced by the standard l2 Euclidean inner product.

- Lee–Yang theorem: The Lee-Yang theorem in statistical mechanics was first proved for the Ising model by future Nobel laureates Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang in 1952. The theorem states that if partition functions of certain models in statistical field theory with ferromagnetic interactions are considered as functions of an external field, then all zeros are purely imaginary, or on the unit circle after a change of variable.[74][b]

- Pu's inequality: In differential geometry, Pu's inequality is an inequality proved by Pao Ming Pu for the systole of an arbitrary Riemannian metric on the real projective plane RP2.

- Siu's semicontinuity theorem: In complex analysis, the Siu semicontinuity theorem implies that the Lelong number of a closed positive current on a complex manifold is semicontinuous. More precisely, the points where the Lelong number is at least some constant form a complex subvariety. This was conjectured by Harvey & King (1972) and proved by Siu (1973, 1974).

- Sun's curious identity: In combinatorics, Sun's curious identity is the following identity involving binomial coefficients, first established by Zhi-Wei Sun in 2002:

- Tsen rank: A Tsen rank of a field describes conditions under which a system of polynomial equations must have a solution in the field. It was introduced by mathematician Chiungtze C. Tsen in 1936.[75]

- Wu's method: Wu's method was discovered in 1978 by Chinese mathematician Wen-Tsun Wu.[76] The method is an algorithm for solving multivariate polynomial equations, based on the mathematical concept of characteristic set introduced in the late 1940s by J.F. Ritt.[77]

- Yunnan Baiyao[78]

See also

- Chinese exploration

- List of China-related topics

- List of Chinese inventions

- List of inventions and discoveries of Neolithic China

- History of Chinese archaeology

- History of science and technology in China

- History of typography in East Asia

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d Ho (1991), 516.

- ^ Lu, Gwei-Djen (25 October 2002). Celestial Lancets. Psychology Press. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-0-7007-1458-2.

- ^ a b Needham (1986), Volume 3, 89.

- ^ Medvei (1993), 49.

- ^ McClain and Ming (1979), 206.

- ^ McClain and Ming (1979), 207–208.

- ^ McClain and Ming (1979), 212.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 218–219.

- ^ Kuttner (1975), 166–168.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 227–228.

- ^ a b Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 223.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 24–25, 121.

- ^ Shen, Crossley, and Lun (1999), 388.

- ^ Straffin (1998), 166.

- ^ Chan, Clancey, Loy (2002), 15.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 614.

- ^ Sivin (1995), III, 23.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 603–604, 618.

- ^ Kangsheng Shen, John Crossley, Anthony W.-C. Lun (1999): "Nine Chapters of Mathematical Art", Oxford University Press, pp.33–37

- ^ Thorpe, I. J.; James, Peter J.; Thorpe, Nick (1996). Ancient Inventions. Michael O'Mara Books Ltd (published March 8, 1996). p. 64. ISBN 978-1854796080.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, 106–107.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, 538–540.

- ^ Nelson, 359.

- ^ Shen, pp.27, 36–37

- ^ Wu Wenjun chief ed, The Grand Series of History of Chinese Mathematics Vol 5 Part 2, chapter 1, Jia Xian

- ^ a b c McLeod & Yates (1981), 152–153 & footnote 147.

- ^ Aufderheide et al., (1998), 148.

- ^ Salomon (1998), 12–13.

- ^ Martzloff, Jean-Claude (1997). "Li Shanlan's Summation Formulae". A History of Chinese Mathematics. pp. 341–351. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33783-6_18. ISBN 978-3-540-33782-9.

- ^ C. J. Colbourn; Jeffrey H. Dinitz (2 November 2006). Handbook of Combinatorial Designs. CRC Press. pp. 525. ISBN 978-1-58488-506-1.

- ^ a b Selin, Helaine (2008). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer (published March 17, 2008). p. 567. ISBN 978-1402049606.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 91.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 90–91.

- ^ Teresi (2002), 65–66.

- ^ a b Needham (1986), Volume 3, 90.

- ^ Neehdam (1986), Volume 3, 99–100.

- ^ a b Berggren, Borwein & Borwein (2004), 27

- ^ Arndt and Haenel (2001), 177

- ^ Wilson (2001), 16.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 100–101.

- ^ Berggren, Borwein & Borwein (2004), 24–26.

- ^ Berggren, Borwein & Borwein (2004), 26.

- ^ Berggren, Borwein & Borwein (2004), 20.

- ^ Gupta (1975), B45–B48

- ^ Berggren, Borwein, & Borwein (2004), 24.

- ^ Sivin (1995), III, 17–18.

- ^ Sivin (1995), III, 22.

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 3, 278.

- ^ Sivin (1995), III, 21–22.

- ^ Elisseeff (2000), 296.

- ^ Hsu (1988), 102.

- ^ Croft, S.L. (1997). "The current status of antiparasite chemotherapy". In G.H. Coombs; S.L. Croft; L.H. Chappell (eds.). Molecular Basis of Drug Design and Resistance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5007–5008. ISBN 978-0-521-62669-9.

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad (12 September 2011). "Lasker Honors for a Lifesaver". The New York Times.

- ^ Tu, Youyou (11 October 2011). "The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine". Nature Medicine.

- ^ McKenna, Phil (15 November 2011). "The modest woman who beat malaria for China". New Scientist.

- ^ Chen, J.R. (1966). "On the representation of a large even integer as the sum of a prime and the product of at most two primes". Kexue Tongbao. 17: 385–386.

- ^ Chen, J.R. (1973). "On the representation of a larger even integer as the sum of a prime and the product of at most two primes". Sci. Sinica. 16: 157–176.

- ^ Chen, J. R. (1966). "On the representation of a large even integer as the sum of a prime and the product of at most two primes". Kexue Tongbao 17: 385–386.

- ^ Cheng, Shiu Yuen (1975a). "Eigenfunctions and eigenvalues of Laplacian". Differential geometry (Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., Vol. XXVII, Stanford Univ., Stanford, Calif., 1973), Part 2. Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society. pp. 185–193. MR 0378003.

- ^ Chavel, Isaac (1984). Eigenvalues in Riemannian geometry. Pure Appl. Math. Vol. 115. Academic Press.

- ^ Chern, S. S. (1946). "Characteristic classes of Hermitian Manifolds". Annals of Mathematics. Second Series. 47 (1). The Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 47, No. 1: 85–121. doi:10.2307/1969037. ISSN 0003-486X. JSTOR 1969037.

- ^ S Darougar, B R Jones, J R Kimptin, J D Vaughan-Jackson, and E M Dunlop. Chlamydial infection. Advances in the diagnostic isolation of Chlamydia, including TRIC agent, from the eye, genital tract, and rectum. Br J Vener Dis. 1972 December; 48(6): 416–420; TANG FF, HUANG YT, CHANG HL, WONG KC. Further studies on the isolation of the trachoma virus. Acta Virol. 1958 Jul–Sep;2(3):164-70; TANG FF, CHANG HL, HUANG YT, WANG KC. Studies on the etiology of trachoma with special reference to isolation of the virus in chick embryo. Chin Med J. 1957 Jun;75(6):429-47; TANG FF, HUANG YT, CHANG HL, WONG KC. Isolation of trachoma virus in chick embryo. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1957;1(2):109-20

- ^ Ji Qiang; Ji Shu-an (1996). "On the discovery of the earliest bird fossil in China and the origin of birds" (PDF). Chinese Geology. 233: 30–33.

- ^ Browne, M.W. (19 October 1996). "Feathery Fossil Hints Dinosaur-Bird Link". New York Times. p. Section 1 page 1 of the New York edition.

- ^ Chen Pei-ji, Pei-ji; Dong Zhiming; Zhen Shuo-nan (1998). "An exceptionally preserved theropod dinosaur from the Yixian Formation of China" (PDF). Nature. 391 (6663): 147–152. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..147C. doi:10.1038/34356. S2CID 4430927.

- ^ Sanderson, K. (23 May 2007). "Bald dino casts doubt on feather theory". News@nature. doi:10.1038/news070521-6. S2CID 189975591. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Cohn 2003, §9.1

- ^ Hua Loo-keng (1938). "On Waring's problem". Quarterly Journal of Mathematics. 9 (1): 199–202. Bibcode:1938QJMat...9..199H. doi:10.1093/qmath/os-9.1.199.

- ^ Sant S. Virmani, C. X. Mao, B. Hardy, (2003). Hybrid Rice for Food Security, Poverty Alleviation, and Environmental Protection. International Rice Research Institute. ISBN 971-22-0188-0, p. 248

- ^ Wolf Foundation Agricultural Prizes

- ^ Huang-Minlon (1946). "A Simple Modification of the Wolff-Kishner Reduction". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 68 (12): 2487–2488. doi:10.1021/ja01216a013.

- ^ Huang-Minlon (1949). "Reduction of Steroid Ketones and other Carbonyl Compounds by Modified Wolff--Kishner Method". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 71 (10): 3301–3303. doi:10.1021/ja01178a008.

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 4, p. 510 (1963); Vol. 38, p. 34 (1958). (Article)

- ^ Yang, C. N.; Lee, T. D. (1952). "Statistical Theory of Equations of State and Phase Transitions. I. Theory of Condensation". Physical Review. 87 (3): 404–409. Bibcode:1952PhRv...87..404Y. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.87.404. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ^ Tsen, C. (1936). "Zur Stufentheorie der Quasi-algebraisch-Abgeschlossenheit kommutativer Körper". J. Chinese Math. Soc. 171: 81–92. Zbl 0015.38803.

- ^ Wu, Wen-Tsun (1978). "On the decision problem and the mechanization of theorem proving in elementary geometry". Scientia Sinica. 21.

- ^ P. Aubry, D. Lazard, M. Moreno Maza (1999). On the theories of triangular sets. Journal of Symbolic Computation, 28(1–2):105–124

- ^ Exum, Roy (December 27, 2015). "Roy Exum: Ellen Does It Again". The Chattanoogan.

Sources

- Arndt, Jörg, and Christoph Haenel. (2001). Pi Unleashed. Translated by Catriona and David Lischka. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-66572-2.

- Aufderheide, A. C.; Rodriguez-Martin, C. & Langsjoen, O. (1998). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55203-6.

- Berggren, Lennart, Jonathan M. Borwein, and Peter B. Borwein. (2004). Pi: A Source Book. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-20571-3.

- Chan, Alan Kam-leung and Gregory K. Clancey, Hui-Chieh Loy (2002). Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-259-7

- Cohn, Paul M. (2003). Further algebra and applications (Revised ed. of Algebra, 2nd ed.). London: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-85233-667-6. Zbl 1006.00001.

- Elisseeff, Vadime. (2000). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-222-9.

- Gupta, R C. "Madhava's and other medieval Indian values of pi," in Math, Education, 1975, Vol. 9 (3): B45–B48.

- Ho, Peng Yoke. "Chinese Science: The Traditional Chinese View," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 54, No. 3 (1991): 506–519.

- Hsu, Mei-ling (1988). "Chinese Marine Cartography: Sea Charts of Pre-Modern China". Imago Mundi. 40: 96–112. doi:10.1080/03085698808592642.

- Harvey, F. Reese; King, James R. (1972). "On the structure of positive currents". Inventiones Mathematicae. 15 (1): 47–52. Bibcode:1972InMat..15...47H. doi:10.1007/BF01418641. ISSN 0020-9910. MR 0296348. S2CID 121825526.

- McLeod, Katrina C. D.; Yates, Robin D. S. (1981). "Forms of Ch'in Law: An Annotated Translation of The Feng-chen shih". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 41 (1): 111–163. doi:10.2307/2719003. JSTOR 2719003.

- McClain, Ernest G.; Shui Hung, Ming (1979). "Chinese Cyclic Tunings in Late Antiquity". Ethnomusicology. 23 (2): 205–224. doi:10.2307/851462. JSTOR 851462.

- Medvei, Victor Cornelius. (1993). The History of Clinical Endocrinology: A Comprehensive Account of Endocrinology from Earliest Times to the Present Day. New York: Pantheon Publishing Group Inc. ISBN 1-85070-427-9.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Salomon, Richard (1998), Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509984-2.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

- Straffin Jr, Philip D. (1998). "Liu Hui and the First Golden Age of Chinese Mathematics". Mathematics Magazine. 71 (3): 163–181. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1998.11996627.

- Teresi, Dick. (2002). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science–from the Babylonians to the Mayas. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83718-8.

- Wilson, Robin J. (2001). Stamping Through Mathematics. New York: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.