| MacDonald House bombing | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (Konfrontasi) | |

The Straits Times on 11 March 1965, with initial reports on the bombing | |

| |

| Location | Singapore |

| Coordinates | 1°17′57.11″N 103°50′45.73″E / 1.2991972°N 103.8460361°E |

| Date | 10 March 1965 3:07 pm (UTC+08:00) |

| Target | MacDonald House |

Attack type | Bombing, mass murder, terrorist attack |

| Weapons | Nitroglycerin bomb |

| Deaths | 3 |

| Injured | 33 |

| Victims | Elizabeth Suzie Choo Juliet Koh Mohammed Yasin bin Kesit |

| Perpetrators | Indonesian Marine Corps |

| Assailants | Harun Thohir Usman bin Haji Muhammad Ali |

No. of participants | 2 |

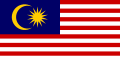

| Motive | Opposition to the formation of Malaysia, terrorism |

| Accused | Harub bin Said Osman bin Mohammed Ali |

| Verdict | Death |

| Convictions | Guilty |

| Charges | Murder (×3) |

| History of Singapore |

|---|

|

|

|

The MacDonald House bombing occurred in Singapore on 10 March 1965 at 3:07 pm local time when a bomb planted in the MacDonald House at Orchard Road exploded, instantly killing two and injuring 33 others. Part of the building was also damaged by the bomb. A victim of the bombing died two days later after being in a coma. The bombing affected bilateral relationships between Indonesia and Singapore.

The nitroglycerin bomb was planted by Indonesian marines Harun bin Said and Osman bin Haji Muhammad Ali as part of the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (Konfrontasi), a conflict between Indonesia and Malaysia over Indonesia's opposition to the creation of Malaysia. They were originally instructed to bomb a power station but went to the MacDonald House instead. At the time, the building was used by the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC), the Australian High Commission and the Japanese Consulate. Both marines subsequently attempted to flee Singapore but were apprehended by the Police Coast Guard. They were charged with the murders of three victims, although the bombing itself was not mentioned in the charges. They were put to trial in the High Court and after a 13-day trial, were found guilty for their charges of murder and sentenced to death. Despite multiple appeals, including a clemency plea from President of Indonesia Suharto, they were hanged on 17 October 1968, causing about 300 students to raid the Singapore Embassy in Jakarta.

Following the bombing, security measures for buildings increased, particularly with packages. The bombing strained bilateral relationships between Indonesia and Singapore until 1973, when Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew went to Indonesia and scattered flowers over the marines' graves, largely restoring bilateral relationships between the two countries. Singapore–Indonesia bilateral relationships were affected again in 2014 following the naming of the KRI Usman Harun, which was named after Harun and Osman. Indonesia officially apologised for the naming but clarified that the naming is irreversible. A memorial at Dhoby Ghaut Green dedicated to the victims of the Konfrontasi was opened in 2015.

Background

[edit]Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation

[edit]The Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation (also called the Konfrontasi) was a conflict between Indonesia and Malaysia that took place between 1963 to 1966. The Konfrontasi was started by Indonesia since it opposed the formation of Malaysia, perceiving it to be a "neo-colonial project" for the British.[1] Indonesian saboteurs mounted a campaign of terror in Singapore, then a major state and city within Malaysia. There were a total of 37 bombings from 1963 to 1966. The saboteurs were trained to attack military installations and public utilities. However, when the saboteurs failed in their attempts to attack these installations that were heavily guarded, they set off bombs indiscriminately to create panic and disrupt life in Singapore as well as in Malaysia.[2]

By 1964, bomb explosions became frequent. To help the police and army defend Singapore from these attacks, a volunteer force was set up. More than 10,000 people signed up as volunteers. Community centers served as bases for the volunteers to patrol their neighbourhoods.[2] In schools, students underwent bomb drills. The government also warned Singaporeans not to handle any suspicious-looking parcels in the buildings or along streets. Despite the efforts of the British, small groups of saboteurs managed to infiltrate the island and plant bombs. By March 1965, a total of 29 bombs had been set off in Singapore.[2]

MacDonald House

[edit]The MacDonald House is a 10-storey office building in Orchard Road, Singapore. Built for the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC), it is the first building in Southeast Asia to be air-conditioned. Land for the building was acquired in 1946 and work on the building began in May 1947.[3][4] The building opened on 2 July 1949 and was given its name after then-Governor General of Singapore Malcolm MacDonald.[5][6] At the time of the bombing, it housed the Australian High Commission, which moved their office from Robinson Road to the building by September 1951, and the Japanese Consulate.[7] MacDonald house is located just 1.4 kilometres (0.87 mi) from The Istana, the official residence of the President of Singapore.[8]

Attack

[edit]The two Indonesian marines, Harun Said and Osman bin Haji Mohamed Ali had arrived in Singapore from Java at 11:00 am, wearing civilian clothes and planted the bomb there. They had been instructed to bomb an electric power house but instead headed to MacDonald House and planted the bomb at the mezzanine floor.[2] Goh Nam Soon, a food hawker, smelled a scent similar to "tyres being burnt" and went to the building to investigate. He discovered at a dark corner of the mezzanine, there was a bag with smoke coming out of it and a "hissing" sound, and decided to inform George Conceicao, a staff officer of HSBC, of the "evil smelling smoke".[9] Multiple other witnesses also noticed the smell.[9]

Explosion

[edit]At 15:07 SST (UTC+08:00), the bomb exploded.[2] The bank had closed for business 7 minutes earlier and 150 employees were there at the time of the explosion. The bomb instantly killed two people: 36-year old Elizabeth Suzie Choo, a secretary to the bank manager, and 23-year old Juliet Koh, a clerk, as well as injuring at least 33 others. The Straits Times speculated that "many more would have been killed or injured if the bomb had gone off 10 minutes later".[7] It was also reported by The Straits Times that many workers initially thought it was a thunderclap as it was heavily raining at the time. The bomb damaged parts of the building, including an inner wall at the mezzanine floor, lift doors, and windows up to 9 storeys. It also caused an elevator to fall to the basement, with the occupants having to pry open the doors.[7][9] The surroundings of the building was also affected by the explosion; the windscreens of cars were shattered and neon signs fell to the ground.[7] Later examination of the building showed that about 9 to 11 kilograms (20 to 24 lb) of nitroglycerine explosives were used for the bomb.

By 3:30 pm, the Reserve Unit arrived at the site to control the crowd, with policemen already diverting traffic in Penang Road and Tank Road. A station wagon belonging to the Australian High Commission had to be pushed from the middle of the road to the side to let ambulances pass. High-ranking police officers from Pearl's Hill was soon at the scene, followed by the British Army's bomb disposal squad. Around that time, the General Hospital was "crammed" with relatives and friends of the injured, with all doctors and nurses activated for emergency duties.[7] In MacDonald House, workers in the upper floor were ordered to vacate the building via the fire escape at the back of the building over the possibility of a second bomb or more walls caving in. Once the building was cleared, only policemen and foreign news correspondents were allowed at the site, with local news correspondents driven away such as a Sin Chew Jit Poh reporter manhandled by an inspector. By 5:00 pm, a team from the Health Department arrived at the site to clean up the shattered glass on the road as it stopped raining.[7] On 12 March, 45-year old Mohammed Yasin bin Kesit, a driver who slipped into a coma from the blast, died, becoming the third victim of the bombing.[10] It was rumoured by workers that a disgruntled employee or the Bank Employee's Union, following a dispute, caused the explosion, though this was denied by HSBC's bank manager for Malaysia S. F. T. B Lever, who said that "I am not prepared to accept that the union will try to bomb the bank because of a dispute. That is an entirely irresponsible statement. I am fully convinced that it has nothing to do with the union or any of the staff of the bank".[11] The Special Investigations Section of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) interviewed several people in connection to the attack.[11]

Arrest

[edit]Harun and Osman boarded a bus in Orchard Road after planting the bomb.[12] Afterwards, they tried to return to Indonesia via a motorboat, though it either sprung a leak or hit an object.[13] They were floating on a piece of plank until they were picked up by Lim Ah Paw, a bumboat operator. Harun claimed both of them were fishermen, though when asked by Lim to present his identity card, Harun claimed it fell in ocean. Lim then told his helmsman to hail a passing police boat.[14] When questioned by the police, Harun said he was a farmer whilst Osman was a fisherman. Both were charged with entering a controlled area. When Marine Police Inspector Mahamed bin Haji Ali spoke of them to Inspector Hill, who was in charge of the MacDonald House bombing investigation. Hill took over the case as he thought the two could assist with the bombing investigation. It was later discovered Harun and Osman were the perpetrators behind the bombing. On 15 March, the two marines were charged in a magistrate's court for "knowingly caus[ing]" the deaths of the three victims, though the bombing is not mentioned within the charges.[15] Harun and Osman were remanded in police custody.[15] The case came up for mention week later on 22 March, though magistrate Sachi Saurajen ordered for the two be further remanded.[16] On 5 April, Harun and Osman were ordered to stand trial in the High Court, with senior inspector T. S. Zain submitting a certificate for the two to be trialed without holding a preliminary enquiry under the 1964 Emergency Criminal Trials Regulations.[17]

The two would have the same charges be applied by the High Court on 17 May, with both pleading not guilty. Director of Public Prosecutions Dalip Singh requested for the case to be adjourned indefinitely, though this was rejected by Justice Ambrose, who "[didn't] think it was proper in a criminal case to have the case be adjourned sine die".[18] Singh then requested for the case to be postponed until May 31, which was granted.[18] The case was postponed again from 30 August until the next Assizes, with 150 witnesses to testify for the case.[19]

Trial

[edit]The trial began on 4 October 1965, with Justice Chua presiding over the trial. Inche Kamil Suhaimi, who was assigned to Harun and Osman, said the two were "seeking protection" under the Geneva Convention since they were members of Indonesian Armed Forces and should be treated as prisoners of war, whilst Senior Crown Counsel Francis T. Seow contested this claim and alleged that the two were "mercenary soldiers" who were paid $350 to carry out a "particular assignment".[20] Inche alleged there had been an attempt obstruct the case's "flow of justice", where he claimed that Osman and Harun's military uniforms, which were worn in previous High Court hearings, were taken away by prison authorities, with one of them allegedly told that he would not be tried in court if he were to wear the uniform.[20] Seow presented the uniform to the court, where he alleged that the Osman and Harun received them from other Indonesian prisoners and that they took off their uniforms when separated from each other as "they were assuming an identity to which they were not legally entitled".[20] When called for a cross-examination by Seow, Osman denied that when he and Harun were picked up, they claimed they were from Kampong Kapor in Singapore, as well as denying that he was bare-bodied and only wearing shorts when rescued, instead in uniforms. Harun denied to be a mercenary, instead claiming that he is a regularly-paid soldier, and denying that he received the military uniform from an Indonesian when remanded as well as information on the Korps Kommando Operasi's military structure from other Indonesian prisoners.[20]

On the second day of the trial, seven witnesses were called to the stand by Seow against Harun and Osman's claims of wearing uniforms when picked up. Lim Ah Paw, the bumboat operator, testified when he picked up the two, Harun was wearing a sports shirt and long trousers whilst Osman was bare-bodied and only wearing long trousers.[14] Four members of the police gave similar accounts to Lim's. Wong Kee Huat of Outram Prison said that the two were in civilian clothing when they were administered in the remand until a few days later, when 40 prisoners, said to have been captured in the Pontian Landing in Johor, were brought to prison.[14] 10 of the 40 were wearing military uniforms that were allowed to be kept and according to Wong, there were opportunities for them to give the uniform to Osman and Harun.[14] Wong did not take action until another police officer noticed that Osman and Harun were wearing uniforms. However, Wong stressed that he could not be sure that the uniforms were taken from the other prisoners as that was his presumption.[14] When recalled to the stand, Osman claim that he wore his uniform until two days after his arrest, when it was taken away by a police officer and his and Harun's were given back to them cleaned.[14] Osman also said that he and Harun were in civilian clothing during the lower court's hearings.[14] On the third day, Seow called in two police photographers to testify against the accused's claim of wearing military uniforms at the time of the explosion. The defendant asked the judge to give Osman and Harun the benefit of the doubt, though this was overruled by Chua, who said:[21]

"The evidence is overwhelming that when the two accused were picked up in Singapore waters by the bumboat-man, they were not in military uniform... I also found in the evidence that when picked up, the two accused claimed to be fishermen, whose boat had capsized. Later to an inspector of police, the first accused claimed to be a fishermen [sic], and the second accused, a farmer. The two accused claim to be members of the regular armed forces of the Republic of Indonesia. They also claim that they are prisoners of war under Article 4 (A1) of the Conventions of 1949. The onus of proving that they are members of the regular armed forces of the Republic of Indonesia lies on the two accused. They have failed to discharge their onus. In any case, I have no doubt that they are not members of the regular armed forces of the Republic of Indonesia. Even if they are members of the regular armed forces of the Republic of Indonesia, they are not in my opinion, entitled to the status of prisoners of war. In my view, members of the enemy armed forces who are combatants, and who come here with the assumption resemblance of peaceful pursuits, and divesting themselves of the character or appearance of soldiers and are captured, such persons are not entitled to the privileges of prisoners of war."

After 13 days, on 20 October, Osman and Harun were found guilty on all three murder chargers and were sentenced to death. Justice Chua described the bombing as a "cowardly act" and that "there [was] only one sentence that [he] can pass".[22] Appeals were made by Inche, who urged the judge to give both defendants the benefit of the doubt, though this was rejected by Chua as "they were beyond any doubt on all the three murder charges".[22] Harun and Osman also appealed against the sentencing,[22] which began on 31 August 1966 in the Federal Court in front of a group of judges, justices Wee Chong Jin, Tan Ah Tah, and Ambrose. Harun and Osmam were represented by A. J. Barga whilst Francis Seow represented the public prosecutor. Barga argued that they were "protected persons" under the Geneva Convention Act 1962 as Chua pointed out that there was a conflict between Indonesia and Malaysia. However, Seow said that there was "overwhelming evidence" that Osman and Harun were not part of Indonesia's regular armed forces. Seow also argued that the bombing was not "a war-like action" but a "murderous action" to civilians as it was conducted during peak hour, which is forbidden by the Geneva Convention Act.[23] The appeal was rejected by the court on 6 October,[24] though Harun and Osman were granted special leave to appeal by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London.[25]

As they were in civilian clothes and had targeted a civilian building, the two men were tried in Singapore for the murder of the three people who died in the blast. They were convicted and hanged in Changi Prison on 17 October 1968.[26][27][28]

Aftermath

[edit]MacDonald House and Orchard Road

[edit]

Repair works for the building begun on 11 March 1965. The building was declared safe by P.W.D engineers and architects, with workers accessing the upper floors via the fire escape staircase. It was expected that the windows of the ground floor will be replaced by the next day, though it was estimated that it would take at least a week for the glass fronts of the buildings affected by the bombing to be fully repaired. HSBC and the Australian Trade Commission was opened for business whilst the Australian High commission temporarily moved offices to one of their employee's home in Orange Grove Road. Some businesses were closed due to a lack of staff. The closed stretch of Orchard Road opened on 11:30 am, where it was revealed that Penang Road and Clemenceau Avenue were congested due to the closed stretch.[11] It was estimated that the cost of the damages in MacDonald House were up to $250,000.[29] A bomb hoax occurred in Orchard Road on 18 March, where a caller threatened to blow up Amber Mansions, resulting in a stretch of Orchard Road to be temporarily closed. It was reopened 15 minutes after the bomb was due to go off.[30]

Heightened security

[edit]Following the explosion, a warning was issued by the government on 11 March 1965 for the general public to be vigilant of "mischievous and irresponsible elements" after a bomb scare at the National Library, half a mile from MacDonald House.[11] The Singapore International Chamber of Commerce (SICC) decided to establish "security committees" on 15 March to protect its members' buildings from being sabotaged by Indonesian agents.[31] The SICC also listed four precautionary measures that businesses should take, being control of entrances, inspection of identity cards, disclosure of package contents from unknown persons, and treatment of packages.[32][33] SICC members such as the Cathay Organisation and Shaw Organisation started inspecting packages, along with other businesses in the city. It was reported by a security firm that after the bombing, "there has been an increased 'security consciousness'. We have been swamped with requests for security guards and advice on security measures from firms and the public".[32] Vulnerable buildings such as Pasir Panjang power station, which was a target by several Indonesia military agencies, had its security precautions strengthened.[33]

Allegations of discrimination against local news reporters

[edit]On 13 March 1965, the Singapore National Union of Journalists (SNUJ) sent a letter to acting Commissioner of Police A. T. Rajah criticising the police's "discriminatory and strong-arm treatment" of Malaysian news reporters, referring to the manhandling incident at the MacDonald House bombing. The letter also alleged that this was not the first time such incident occurred and requested for the union and the acting-Commissioner to meet.[34]

When asked by news reporters about the manhandling incident, Minister of Home Affairs Ismail bin Dato Abdul Rahman revealed that he ordered a full enquiry into the incident, and that police officers found guilty of manhandling news reporters will be punished, though refused to comment further to be impartial to the police.[35] By 15 March, thirteen news reporters were interviewed and the SNUJ was to meet with Rajah on 18 March to discuss police manhandling incidents towards local news reporters, as well as for the two groups to better cooperate.[34] By 19 March, the probe was at its final stage, with a full report to be sent to the Inspector-General of Police by the next day or early next week.[36] The probe would be completed on 22 March and Rajah would receive the report by 29 March.[37][38]

After reading the report, it was determined by Ismail that the police officer who twisted the news reporter, Inspector K. Dyrian, would not be charged as according to Ismail, the officer had no intention of discrimination between local and foreign journalists. Ismail speculated that Dyrian "lost his head" when he applied the twist to the reporter.[39][40][41] The SNUJ and Malaya National Union of Journalist criticised the decision, calling for an "impartial enquiry" and the release of the full report.[42][43] However, the Ministry of Home Affairs refused to release the report, adding that "all future action should be designed to improve relations [between the police and the press] and not exacerbate them".[44]

Effect on Indonesia–Singapore bilateral relations

[edit]Singapore would gain independence and leave Malaysia on 9 August 1965, just five months after the bombing. In March 1967, the President of Indonesia, Sukarno, who had initiated the Konfrontasi, resigned from the presidency under pressure by Indonesian military general Suharto amidst the 30 September Movement. A clemency plea by Suharto, who assumed the position of President, was rejected. The Singapore Embassy in Jakarta was occupied on the day of the saboteurs' hanging by 300 students.[45][46]

Bilateral relations between Singapore and Indonesia would improve after 1973, when Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, visited the graves of Harun and Osman in Indonesia (nyekar) and scattered flowers on them. As Indonesians believe in life cycles, flowers are sprinkled on graves to decorate and make it fragrant, allowing peaceful rest of the deceased.[47] This was followed by Suharto's visit to Singapore in 1974.[48] From the 1980s, exchanges would sharply increase between the two countries in politics, tourism, defence, business, and student and community-based exchanges.[47]

Warship-naming controversy

[edit]In February 2014, it was reported in the Kompas Daily that one of the three new Bung Tomo-class corvette warships would be named the KRI Usman Harun after Harun and Osman, which caused concern in Singapore.[49][50] Then-coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs Djorko Suyanto defended the decision.[51] In response to the naming, Singapore banned the ship from entering its water.[52] Suyato responded to the ban by stating "the ship has not even arrived yet, so what’s the fuss"?[52] They also withdrew its delegation from an international defence meeting, after two Indonesian men at the event were seen dressed in uniform.[52]

General Moeldoko, Indonesia's military chief, apologised for the naming of the ship, which was accepted by Singapore in a statement by Singapore Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen.[53][54][55][56] Moeldoko however later clarified that the naming of the ship was unfortunately irreversible.[57][58][59][60][61]

Memorial

[edit]On 10 March 2015, 50 years after the bombing, a memorial dedicated to the victims of the Konfrontasi as well as soldiers who died during that period, was unveiled at Dhoby Ghaut Green, situated across MacDonald House.[62] It was built at the recommendation of the Singapore Armed Forces Veterans League (SAFVL) with the objective as a remembrance of the victims, as well as to educate younger generations about the tragedy. The unveiling was officiated by Minister for Culture, Community and Youth Lawrence Wong, as "a lasting reminder of the victims of Konfrontasi, and those who risked their lives defending our country". Religious leaders from the Inter-Religious Organisation also prayed at the site, before laying a wreath on the monument.[63][64]

-

Memorial to the Victims of Konfrontasi, Dhoby Ghaut Green.

-

The plaque on the front of MacDonald House, Singapore, commemorating the 1965 bombing

-

MacDonald House in 2018

-

Osman bin Mohamed Ali (left) and Harun bin Said (right), the perpetrators of the bombing

See also

[edit]- Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation

- Capital punishment in Singapore

- Usman Haji Muhammad Ali

- Harun Thohir

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Singapore, National Library Board. "MacDonald House bomb explosion | Infopedia". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "MacDonald House Bombing". www.roots.sg. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ "MacDonald House is a testimony to courage". The Singapore Free Press (Newspaper supplement). 1 July 1949. pp. 3, 5. Retrieved 6 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ Sunday Times Staff Reporter (12 December 1948). "Strike holds up bank's finish". The Straits Times. p. 7. Retrieved 6 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Mr. Kindness is at new bank". The Straits Times. 3 July 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 7 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "NEW BANK IS OPENED". Sunday Tribune (Singapore). 3 July 1949. p. 2. Retrieved 7 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b c d e f Sam, Jackie; Khoo, Philip; Cheong, Yip Seng; et al. (10 March 1965). "Terror Bomb kills 2 Girls at Bank". The Straits Times (published 11 March 1965). p. 1 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ Nirmala (13 February 2014). "MacDonald House attack still strikes home in S'pore". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 10 August 2025. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b c "Two tell of 'smell' before explosion". The Straits Times (published 8 October 1965). 7 October 1965. p. 9. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Bomb victim No. 3 dies of wounds". The Straits Times (published 13 March 1965). 12 March 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 8 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b c d "Warning follows library bomb scare". The Straits Times (published 12 March 1965). 11 March 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 8 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Conductor: I was angry at the two Indons..." The Straits Times (published 12 October 1965). 11 October 1965. p. 6. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "TNI AL: Gani bin Arup Sudah Meninggal Dunia, Jejaknya Misterius". detiknews. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Were they in jungle green when rescued?". The Straits Times (published 6 October 1965). 5 October 1965. p. 5. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b "BANK BOMB: TWO MEN in COURT". The Straits Times (published 16 March 1965). 15 March 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 8 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "ORCHARD ROAD BOMB: TWO AGAIN REMANDED". The Straits Times (published 23 March 1965). 22 March 1965. p. 7. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Mac Donald House blast: Two for trial". The Straits Times (published 6 April 1965). 5 April 1965. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b "Macdonald House blast: 2 charged". The Straits Times (published 18 May 1965). 17 May 1965. p. 4. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Bank bomb case: 150 witnesses to be called". The Straits Times (published 31 August 1965). 30 August 1965. p. 11. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b c d "Captured Indons: PoWs or mercenaries?". The Straits Times (published 5 October 1965). 4 October 1965. p. 12. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Indons not in uniform, says judge".

- ^ a b c "Death for Indon bombers". The Straits Times (published 21 October 1965). 20 October 1965. p. 11. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Judgment reserved in bomb explosion appeal". The Straits Times (published 1 September 1966). 31 August 1966. p. 24. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "MacDonald House bombing: Four fail in appeal".

- ^ "MacDonald House blast: Two get leave to appeal".

- ^ MacDonald House attack still strikes home in S'pore Archived 14 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 13 February 2014

- ^ Sudarmanto, J. B. (2007). Jejak-jejak pahlawan : perekat kesatuan bangsa Indonesia (rev. 2nd ed.). Jakarta: Gramedia Widiasarana Indonesia. pp. 162, 164. ISBN 9789797597160. OCLC 200180907.

- ^ Singapore from Settlement to Nation Pre-1819 to 1971 (6th ed.). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Education. pp. 196–197.

- ^ "MacDonald House suffered $250,000 bomb damage". The Straits Times (published 9 October 1965). 8 October 1965. p. 6. Retrieved 7 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Police close street after 'bomb' hoax". The Straits Budget (published 24 March 1965). 18 March 1965. p. 17. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Plan for safety teams to guard buildings". The Straits Budget (published 24 March 1965). 15 March 1965. p. 9. Retrieved 9 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b "SECURITY MOVE IN MANY FIRMS". The Straits Times (published 19 March 1965). 18 March 1965. p. 4. Retrieved 9 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b Sam, Jackie (15 March 1965). "Security measures are reviewed". The Straits Budget (published 24 March 1965). p. 7. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ a b "Newsmen's union to see chief of police". The Straits Budget (published 24 March 1965). 15 March 1965. p. 13. Retrieved 9 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Minister: Guilty policemen will be punished". The Straits Times (published 18 March 1965). 17 March 2025. p. 12. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Police and newsmen: Probe in final stage". The Straits Times (published 20 March 1965). 19 March 2025. p. 5. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Singapore Police probe ends". The Straits Times (published 23 March 1965). 22 March 2025. p. 11. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "RAJAH GETS REPORT OF NEWSMEN'S CHARGES". The Straits Times (published 30 March 1965). 29 March 1965. p. 22. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "A 'best effort' pledge to PM". The Straits Times. 23 April 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ Krishnan, P. (23 April 1965). "No action against officer who 'lost his head'". The Straits Times. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Ismail clears police". The Straits Times (published 12 May 1965). 11 May 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "'Keep your pledge' plea to Ismail". The Straits Times (published 24 April 1965). 23 April 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "UNIONS CALL FOR FULL REPORT OF THAT 'JUDO INCIDENT'". The Straits Times (published 13 May 1965). 12 May 1965. p. 18. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Bomb row: Ismail not to release report". The Straits Times (published 27 May 1965). 26 May 1965. p. 8. Retrieved 10 March 2025 – via NewspaperSG.

- ^ "Indonesians Wreck Singapore Embassy". The Glasglow Hearld (published 18 October 1968). 17 October 1968. p. 15. Retrieved 12 August 2025 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Jakarta Angry at Hangings".

- ^ a b Sebastian, Leonard C. (2024) [3 May 2024]. "10". In Koh, Gillian (ed.). Commentary On Singapore. Vol. 1: Foreign Policy, Governance And Leadership. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. Overview. ISBN 9789811264566. Retrieved 12 August 2025 – via Google Books.

- ^ Konfrontasi: Why It Still Matters to Singapore, Daniel Wei Boon Chua, RSIS Commentary, No. 054 – 16 March 2015, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University

- ^ "Singapore concerned over naming of Indonesian navy ship after executed commandos". Archived from the original on 7 February 2014.

- ^ Cheney-Peters, Scott (19 February 2014). "Troubled Waters: Indonesia's Growing Maritime Disputes". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Indonesia minister defends move to name warship after marines behind Singapore bombing". Archived from the original on 7 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Jaipragas, Bhavan. "Singapore bans disputed Indonesian navy ship". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ "Singapore Accepts Indonesian Apology for Ship's Name; Bilateral Cooperation Between The Two Militaries to Resume".

- ^ "Singapore accepts Indonesia apology over warship row - ASEAN/East Asia | The Star Online". www.thestar.com.my. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Channel News Asia: Indonesian Armed Forces Chief expresses regret over naming of warship". www.mfa.gov.sg. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Singapura Terima Permintaan Maaf Moeldoko, Nama KRI Usman Harun Tak Diganti" (in Indonesian). 17 April 2014.

- ^ "No apology for ship naming, says Indonesian army chief". www.todayonline.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Kwara, Michelle (18 April 2014). "Indonesia's armed forces chief says "no apology" for warship's name". Yahoo! Singapore. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ antaranews.com. "Moeldoko bantah minta maaf soal KRI Usman Harun – ANTARA News". Antara News (in Indonesian). Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Panglima TNI bantah minta maaf ke Singapura". BBC Indonesia. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "TNI chief clarifies apology, Channel News Asia, 19 April 2014". Gmane.org. 19 April 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Lim, Yan Liang (10 March 2015). "Memorial to victims of Konfrontasi unveiled near MacDonald House". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2025. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Memorial for Konfrontasi victims, heroes unveiled". ChannelNewsAsia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Lim, Yan Liang. "Memorial to victims of Konfrontasi unveiled". AsiaOne. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- David Brazil (1 May 2006). Insider's Singapore. Times Books; National Library Board. ISBN 981204762X.

- Mushahid Ali (23 March 2015). "Konfrantasi: Why Singapore was in Forefront of Indonesian Attacks" (PDF). RSIS Commentary. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.