| Rice riots of 1918 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Ruins of the Okayama Seimai grain merchant building, burned by rioters in August 1918 | |||

| Date | 22 July – 21 September 1918 | ||

| Location | Japan (49 cities, 217 towns, 231 villages) | ||

| Caused by | Post–World War I inflation, rapid increase in the price of rice, and government inaction | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Largely leaderless | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

The rice riots of 1918 (Japanese: 米騒動, Hepburn: kome sōdō) were a series of popular disturbances that swept across Japan from July to September 1918. Lasting for over eight weeks, the riots were the largest, most widespread, and most violent popular uprising in modern Japanese history, ultimately leading to the collapse of the Terauchi Masatake administration. The disturbances began in the small fishing town of Uozu in Toyama Prefecture and spread to nearly 500 locations, including 49 cities, 217 towns, and 231 villages, involving an estimated one to two million participants. The riots marked a new level of labor assertiveness and were described by a Home Ministry report at the time as a "crisis in relations between Labor and Capital".[1]

The immediate cause of the riots was the sharp increase in the price of rice and other commodities following the economic boom of World War I. While a small segment of the population prospered, widespread inflation caused severe economic hardship for both urban and rural consumers. Public anger grew as government attempts to regulate prices proved ineffective, leading to accusations of collusion between officials and profiteering merchants. The nature of the protests varied significantly by region: the initial coastal riots in Toyama were largely non-violent appeals to community norms, while the subsequent urban riots in major cities like Nagoya, Osaka, and Tokyo were more politically charged and violent. A third wave of disturbances in the coalfields took the form of organized labor disputes.

The Terauchi government responded with a "candy and whip" policy of harsh suppression and palliative relief. Over 100,000 troops were deployed to quell the unrest, resulting in dozens of civilian deaths and over 25,000 arrests. Simultaneously, the government established a national relief fund and organized the distribution of subsidized rice, though these measures were often criticized as inadequate.

In the aftermath of the riots, the Terauchi government resigned, paving the way for the appointment of Hara Takashi as the first commoner prime minister and the establishment of the first stable party-led cabinets in Japanese history. The events spurred significant policy reforms in food supply management, colonial agriculture, and social welfare. The riots also served as a major catalyst for the social and political movements of Taishō-era Japan, galvanizing the labor union movement, tenant farmer associations, and campaigns for the rights of women and the burakumin.

Background

[edit]Economic conditions

[edit]The outbreak of World War I in 1914 created a significant economic boom for Japan. As demand from Allied nations for textiles and industrial goods soared, a small segment of the population became wealthy almost overnight. These nouveau riche, or narikin, became a symbol of unjustified wealth and a focus of popular resentment. While this new class of "millionaires" grew by 115 percent between 1915 and 1919, the vast majority of Japanese consumers saw their real spending power decline sharply.[2]

Wartime inflation caused the cost of food, fuel, cloth, and other consumer goods to double. While nominal wages increased, they lagged far behind the spiraling cost of living. Real wages, which had declined by 3 percent in 1915, had fallen by over 30 percent by 1918.[3] This economic hardship had a wide-ranging social impact, with newspaper reports and statistics indicating a general decline in the quality of life and higher rates of contagious diseases like tuberculosis.[3]

The inflation affected not only the poor but also the emerging middle class (chūryū kaikyū), including lower-level government officials, teachers, and clerks, who were sometimes dubbed "paupers in Western clothes" (yōfuku saimin). The purchasing power of minor public servants fell by approximately 50 percent between 1914 and 1918, a greater decline than that experienced by many industrial workers. Unlike factory hands or craftsmen, who could work overtime or take on piecework, salaried workers and officials lacked the time, opportunity, or social sanction to supplement their incomes.[3] This widespread economic distress led to an unprecedented number of wage disputes and walkouts among groups not previously known for labor agitation, including policemen, city clerks, and even workers at the Imperial Household Agency.[4]

Government policy and political climate

[edit]Despite growing public discontent and clear warnings from social observers, Japan's major political parties—the Rikken Seiyūkai, the Kenseikai, and the Rikken Kokumintō—offered few concrete measures to address the economic crisis. Party leaders of the era, such as Hara Takashi, Katō Takaaki, and Inukai Tsuyoshi, were generally elitist and saw their role as guiding public opinion rather than following it. Their primary political goal was to expand the power of their respective parties within the Meiji constitutional order, often through alliances of convenience and back-room deals with the genrō, or elder statesmen, who still held significant influence over the government.[5] The electorate was small, with only 2.5 percent of the population eligible to vote in 1917, so parties were more responsive to their wealthy patrons—including major commercial concerns like Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Suzuki Shōten—than to the concerns of the unenfranchised masses.[6]

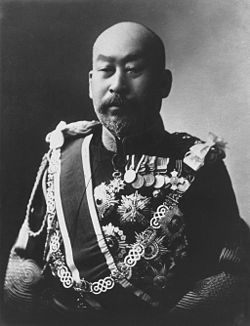

The government of Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake, a "transcendent" cabinet of non-party appointees, responded belatedly to the "rice price revolution".[7] As the riots spread, government officials grew increasingly alarmed by the influence of international events, particularly the Bolshevik Revolution. Communications minister Den Kenjirō wrote in his diary that "superficial democratic thought and radical Communist ideology are little by little eating away at the brains of the lower classes."[8] The government's fundamental error was to treat the problem as one of distribution and speculation rather than one of an absolute shortage of rice.[7] In 1917, Minister of Agriculture and Commerce Nakashōji Ren pushed through the Excess Profits Ordinance, which was intended to curb profiteering and hoarding, but the measure was market-oriented, contained weak penalties, and failed to address the underlying imbalance of supply and demand.[9] Penalties were mild, with a maximum of three months in jail and a fine of 100 yen, and first-time offenders were usually only warned; not a single major rice dealer was prosecuted as a second-time offender in 1918.[10]

The government also stepped up rice imports, but the policy was too little, too late. By involving major trading companies like Suzuki Shōten in the import program, the policy also increased popular suspicion of collusion between the Terauchi cabinet and the narikin.[10] A nationwide survey of rice reserves conducted in July 1918 backfired; by failing to release the results, the government fueled rumors of dire shortages and set off a new frenzy of speculative buying that sent prices even higher.[11] By the last week of July 1918, a shō (about 1.8 liters; 0.40 imp gal; 0.48 U.S. gal) of polished rice cost as much as 50 sen, a 60 percent jump in just thirty days.[11]

The riots

[edit]

The 1918 disturbances were unprecedented in modern Japanese history in their scale, scope, and violence. The unrest began on 22 July in the small fishing town of Uozu in Toyama Prefecture. For eight weeks, protests continued across the country, occurring in 49 cities, 217 towns, and 231 villages. Major urban riots occurred between 9 and 20 August in Kyoto, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, and Tokyo. The final phase of the rioting took place in the coal-mining areas of western Japan between 20 and 27 August.[12] Only the Ryukyus and several prefectures in the rural Tōhoku region remained riot-free.[13]

Estimates of the total number of participants range from a low figure of 700,000 to 1–2 million[14] to a high of 10 million, out of a total Japanese population of about 56 million.[13] The actions taken by protesters varied widely, from non-violent petitions and work stoppages to armed attacks on government offices, the destruction of merchant property, and full-scale street battles with police and troops.[13]

Outbreak in Toyama

[edit]

The first wave of rioting began in the small towns and villages along Toyama Bay. The region, part of Japan's rural "outback" (ura Nihon), was an unlikely starting point for a national disturbance. While undergoing gradual industrialization, its economy was still dominated by traditional occupations like farming, fishing, and migratory labor.[15] The protests in Toyama were not a "rebellion of the belly" caused by absolute poverty, but rather a reaction to the perceived injustice of high rice prices in a region where rice was the most abundant and profitable product.[16] Local residents could see with their own eyes that rice was being shipped out of their ports for sale in urban centers, and they resented the marketing practices that prevented them from consuming locally produced rice at a fair price.[17]

The initial protests were led almost exclusively by women, particularly the wives of fishermen and stevedores. On 22 July 1918, a group of women in Uozu met and decided to boycott the shipping of grain out of the prefecture.[18] Their protest followed a traditional, almost ritualistic pattern of appeals to authority and community norms.[19] Protest leaders, typically middle-aged or older women respected for their work experience and status as household heads, organized sit-ins, marches, and vigils, first appealing to local merchants and officials and then escalating to direct, though largely non-violent, obstruction.[20] Their goal was not to overturn the social order but to have their grievances addressed within the existing system, demanding that community leaders take responsibility for the welfare of the people.[21]

Spread to urban centers

[edit]

Within days of the Toyama shipping boycotts, massive and violent rioting broke out in every major Japanese city.[22] These urban uprisings went far beyond the traditional protests of Toyama in their sweeping indictment of national politics.[23]

The riots in Nagoya, which lasted from 9 to 17 August, were typical of the major urban protests. They began with a mass "citizens' rally" (shimin taikai) in Tsuruma Park, where speakers condemned the government's rice policy, hoarding by merchants, and the greed of the narikin.[24] The rallies quickly escalated into city-wide rioting. Crowds thousands strong marched through the central districts, attacking the offices of rice dealers, the rice exchange, and government buildings.[25] The new wave of labor assertiveness that coincided with the riots led to major walkouts, including strikes that shut down the Tokyo Arsenal and the Osaka streetcar system. By 1919, industrial relations could no longer be persuasively represented as a private matter between paternalistic employers and grateful workers.[14] Unlike in Toyama, the urban rioters did not appeal to the paternalism of authorities but instead expressed an explicitly political consciousness, identifying themselves as citizens of Japan and demanding changes to government policy.[23] Speakers at the rallies demanded the resignation of the Terauchi cabinet and condemned the police for suppressing their right to protest.[26] The urban protests were characterized by a higher degree of violence, including arson, looting, and direct, armed confrontations with police and troops.[27]

Coalfield riots

[edit]The final wave of disturbances occurred in Japan's major coal-mining regions, particularly in western Honshu and northern Kyushu. These riots were essentially labor disputes that used the opportunity provided by the nationwide unrest to press for higher wages and better working conditions.[28] Decades of escalating labor disputes had preceded the 1918 riots, as miners protested dangerous working conditions, low pay, and the exploitative naya system of company-controlled labor bosses and housing.[29]

The coalfield riots were distinct from both the rural and urban protests. The miners' demands were not primarily about the consumer price of rice, but about their wages and the power of the company over their lives.[30] Their protests were highly organized, with leaders presenting detailed petitions, setting deadlines for management responses, and threatening strikes or violence if their demands were not met.[31] Their targets were specific to the mining compound: the company store, management offices, and the homes of company officials and unpopular foremen.[32] The coalfield riots were also among the most violent, with miners using dynamite against troops and suffering the heaviest casualties of the entire series of disturbances.[33]

Participants

[edit]The riots involved a broad cross-section of Japanese society, reflecting the widespread nature of economic discontent. Analysis of prosecution records, though incomplete, provides a profile of the participants.

Social and economic profile

[edit]Those prosecuted for rioting were predominantly male (over 80 percent), between the ages of 20 and 49.[34] Most were from the poorer, less-educated levels of society, but relatively few of the "extremely indigent" were arrested.[35] The majority of urban rioters were established workers in traditional trades, such as craftsmen and day laborers, not the rootless or unemployed. In Nagoya, for example, 22 percent of those indicted were craftsmen and 20 percent were laborers.[36] These individuals were not part of a disintegrating fringe, but were stable residents, many with long-standing family roots in their cities, who were integrating themselves into the industrializing economy.[34]

The case of Yamazaki Tsunekichi, an itinerant tinker who became a protest leader in Nagoya and later a socialist politician, illustrates how the riots could move an ordinary citizen into the political process. Initially hesitant, he was angered by rumors of grain importers dumping rice at sea and was drawn into the Tsuruma Park rallies. He discovered a thrill in leading the mass movement and became an active participant in the riots, which he later described as a valuable political education that impressed upon him the inequality inherent in Japanese society.[37]

Role of specific groups

[edit]- Women: While women were the primary instigators and leaders of the initial coastal riots in Toyama, their role was less prominent in the urban disturbances. In cities like Kobe and Tokyo, women and children often participated in the aftermath of a confrontation, crowding around rice shops after male rioters had forced dealers to sell grain at a discount.[38]

- Burakumin: Members of Japan's burakumin outcast communities participated in a spotty, all-or-nothing manner. While some buraku settlements remained completely quiet, others participated with a high degree of local solidarity.[39] Despite constituting less than 2 percent of the population, burakumin accounted for over 10 percent of those arrested, and in some regions, 30 to 40 percent. This was due in part to their tendency to act in identifiable groups and in part to the government's policy of scapegoating them for the unrest.[40]

- Socialists and anarchists: The Japanese Left was an isolated and largely underground movement in 1918 and played a negligible role in the riots. The government, however, was extremely nervous about the potential for "red" agitation and used the riots as a pretext to round up known leftists like Ōsugi Sakae and Arahata Kanson. Of the more than 8,000 people prosecuted for riot-related offenses, only seven were identified as leftists, and none could be classified as a political leader of the protests.[41][42]

- Reservists and youth groups: Members of state-supported local organizations, such as military reservist groups (zaigō gunjin kai) and youth associations (seinen dan), were often called upon to help maintain order. However, in many cases they dragged their heels or openly joined the protests, siding with their communities against outside authorities. In Kyoto, the head of a youth association led attacks on landlords.[43] The lack of discipline among reservists was particularly alarming to government leaders, who saw it as a threat to national stability.[43]

Government response

[edit]The central government's response to the nationwide unrest was a "candy and whip" (ame to muchi) policy, combining harsh suppression with palliative relief efforts. The Home Ministry and the Ministry of Justice wielded the whip, while the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce doled out the candy.[44]

Suppression

[edit]

To prevent the spread of rioting, authorities banned public meetings, censored newspaper reports, and tightened surveillance of suspected radicals and buraku areas.[44] As local police forces proved incapable of controlling the massive crowds, the government undertook an unprecedented mobilization of military force.[11] Estimates of the number of troops deployed vary between 92,000 and 102,000.[45][46] The forces included military police (kenpeitai), infantry regulars, and even navy troops.[46]

The troops did not hesitate to use lethal force, employing swords, rifles, and machine guns against crowds armed with stones, clubs, and bamboo sticks. More than thirty protesters were killed by police or troops, and scores more were wounded. No soldiers or police died at the hands of rioters.[46] The harshest fighting occurred in the mining districts of Yamaguchi and Kyushu.[13]

Over 25,000 people were arrested.[46] The legal process was swift and harsh, designed to make an example of the protesters. In Tokyo, the presiding judge disposed of fifty cases in a single afternoon.[47] Of the 8,185 suspects formally charged, over 5,000 were convicted. Punishments were severe; thirty rioters, mostly from the Kansai region, were sentenced to life at hard labor for crimes like arson.[47]

Relief efforts

[edit]The "candy" portion of the government's policy consisted of a national relief fund and the coordination of local relief efforts. In mid-August, as rioting peaked in major cities, Emperor Taishō donated 3 million yen to the national relief fund, a sum that was quickly supplemented by 10 million yen from the national treasury and millions more from major corporations like Mitsui and Mitsubishi.[47]

These centrally-raised funds were distributed to prefectures to support local relief programs. For the "extremely needy", local officials gave free rice or cash subsidies. For others, they issued discount coupons that could be used to purchase fixed quantities of grain at below-market prices.[48] Sacks of relief grain were often boldly printed with the slogan "Imperial Gift Rice" (onshi mai) to emphasize the source of the generosity.[48]

Public reaction to the relief efforts was mixed. Many complained that the programs did not go far enough and that they excluded the struggling middle class.[49] There was also widespread discontent with the use of imported rice—Korean, Taiwanese, and Southeast Asian—which was considered inferior in taste and quality to Japanese rice. An article in the Osaka Asahi Shimbun noted that the foreign rice was often "full of sand and dust" and that many were buying it only for animal feed.[49] The government's attempts to convince the public of the value of foreign grain, including publishing cooking instructions, did little to overcome popular resistance.[50]

Aftermath and consequences

[edit]The riots marked a significant turning point in modern Japanese history, accelerating the pace of political, social, and economic change.

Political changes

[edit]

The most immediate consequence of the riots was the collapse of the Terauchi administration. On 21 September 1918, Prime Minister Terauchi and his cabinet resigned, taking responsibility for the widespread civil disorder.[51] He was succeeded by Hara Takashi, leader of the Seiyūkai. Hara's appointment as the first commoner prime minister marked a major shift in Japanese politics. It ended the era of "transcendent" cabinets appointed by the genrō and ushered in a period of party-led governments, a key development in Taishō democracy.[51] The genrō Yamagata Aritomo, though disdainful of party politics, recognized that the popular will expressed in the riots could no longer be ignored and did not actively oppose Hara's nomination.[51] Hara, for his part, had condemned the Terauchi cabinet for its reliance on suppression against the popular movements, positioning himself as a more suitable leader to handle the post-riot political climate.[52]

Social and policy reforms

[edit]The riots created what a Home Ministry report called a "crisis in relations between Labor and Capital," forcing a re-examination of Japan's labor-management policies.[1] In the immediate aftermath, the embryonic labor federation Yūaikai saw its membership and militancy surge, transforming it into the Sōdōmei (Japan General Federation of Labor), which in 1919 pledged to "rid the world of the evils of capitalism".[53] The government and political parties were forced to respond to this new level of labor assertiveness. The new Hara government, led by Home Minister Tokonami Takejirō, advanced a policy of "harmony" (kyōchō), which sought to pre-empt horizontal trade unions by encouraging enterprise-based "vertical unions" and reinterpreting the repressive Article 17 of the Police Regulations to permit union organization by "peaceful means" while cracking down on "outside" agitation.[54] In contrast, the opposition Kenseikai party, in direct response to the riots, formulated a more liberal program of social reform in late 1918, including a labor insurance law and a labor union bill modeled on British practices, hoping to build a political coalition with moderate labor.[55]

In the wake of the riots, the government instituted a host of other long-lasting reforms. To prevent future food shortages, the Hara government implemented a fifteen-year land reclamation plan and expanded colonial rice production in Korea and Taiwan.[56] The Rice Law of 1921 created a permanent system for regulating the grain market, giving the state power to adjust import duties and buy or sell rice stocks to control prices.[57]

The riots also spurred a major expansion of social welfare programs. Central and local governments, as well as private philanthropies, stepped up spending on relief. Special government divisions were created to handle social welfare, and cities established subsidized public markets, worker lunchrooms, housing-assistance offices, and day-care facilities.[58] This marked a conceptual shift, as social welfare came to be seen as a responsibility of the state rather than a matter of private charity.[59]

The riots galvanized mass movements across the political spectrum. Energized by the success of the protests, labor unions, tenant farmer associations, and women's rights groups accelerated their activities.[60] The number of labor unions grew from 107 in 1918 to 457 by 1925, and tenant disputes jumped from 85 in 1917 to nearly 2,000 by 1923.[61] In 1922, the Suiheisha (Levelers' Association) was formed as a nationwide organization to fight for the rights of the burakumin.[62] These movements culminated in the passage of the male universal suffrage law in 1925, though this victory was tempered by the simultaneous passage of the repressive Peace Preservation Law.[63]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Garon 1987, p. 39.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1990, p. 2.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 4.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 6.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 11.

- ^ Garon 1987, p. 43.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 12.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1990, p. 15.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c d Lewis 1990, p. 16.

- ^ a b Garon 1987, p. 40.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 34.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 36.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 45, 50.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 47.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 80.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 82.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 84.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 85.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 87, 89.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 90, 112.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 92, 98–100.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 192.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 193, 201.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 208.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 219.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 222.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 207, 226.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 117.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 43.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 116.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 124.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 125.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Garon 1987, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 26.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Garon 1987, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Lewis 1990, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1990, p. 29.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 30.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1990, p. 243.

- ^ Garon 1987, p. 65.

- ^ Garon 1987, p. 42.

- ^ Garon 1987, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Garon 1987, pp. 55–56, 62–63.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 246.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 131–132, 247.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 247.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 248–250.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 249.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 250.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 251.

Works cited

[edit]- Garon, Sheldon (1987). The State and Labor in Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05983-2.

- Lewis, Michael (1990). Rioters and Citizens: Mass Protest in Imperial Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06642-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Beasley, W.G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822168-1.