A serial killer (also called a serial murderer) is an individual who murders three or more people,[1] with the killings taking place over a period of more than one month in three or more separate events.[1][2] Their psychological gratification is the motivation for the killings, and many serial murders involve sexual contact with the victims at different points during the murder process.[3] The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) states that the motives of serial killers can include anger, thrill-seeking, attention seeking, and financial gain, and killings may be executed as such.[4] The victims tend to have things in common, such as demographic profile, appearance, gender, or race.[5] As a group, serial killers suffer from a variety of personality disorders. Most are often not adjudicated as insane under the law.[6] Although a serial killer is a distinct classification that differs from that of a mass murderer, spree killer, or contract killer, there are overlaps between them.

Etymology and definition

[edit]The English term and concept of serial killer are commonly attributed to former Federal Bureau of Investigation special agent Robert Ressler, who used the term serial homicide in 1974 in a lecture at Police Staff College, in Bramshill, Hampshire, England.[7] Author Ann Rule postulates in her 2004 book Kiss Me, Kill Me, that the English-language credit for coining the term goes to Los Angeles Police Department detective Pierce Brooks, who created the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (ViCAP) system in 1985.[8]

The German term and concept were coined by criminologist Ernst Gennat, who described Peter Kürten as a Serienmörder ('serial-murderer') in his article "Die Düsseldorfer Sexualverbrechen" (1930).[9] In his book, Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters (2004), criminal justice historian Peter Vronsky notes that while Ressler might have coined the English term "serial homicide" within the law in 1974, the terms serial murder and serial murderer appear in John Brophy's book The Meaning of Murder (1966).[10] The Washington, D.C., newspaper Evening Star, in a 1967 review of the book:[11]

There is the mass murderer, or what he [Brophy] calls the "serial" killer, who may be actuated by greed, such as insurance, or retention or growth of power, like the Medicis of Renaissance Italy, or Landru, the "bluebeard" of the World War I period, who murdered numerous wives after taking their money.

Vronsky states that the term serial killing first entered into broader American popular usage when published in The New York Times in early 1981, to describe Atlanta serial killer Wayne Williams. Subsequently, throughout the 1980s, the term was used again in the pages of The New York Times, one of the major national news publications of the United States, on 233 occasions. By the end of the 1990s, the use of the term had increased to 2,514 instances in the paper.[12]

When defining serial killers, researchers generally use "three or more murders" as the baseline,[1] considering it sufficient to provide a pattern without being overly restrictive.[13] Independent of the number of murders, they need to have been committed at different times, and are usually committed in different places.[14] The lack of a cooling-off period (a significant break between the murders) marks the difference between a spree killer and a serial killer. The category has, however, been found to be of no real value to law enforcement, because of definitional problems relating to the concept of a "cooling-off period."[15] Cases of extended bouts of sequential killings over periods of weeks or months with no apparent "cooling off period" or "return to normality" have caused some experts to suggest a hybrid category of "spree-serial killer".[10]

In Controversial Issues in Criminology, Fuller and Hickey write that "[t]he element of time involved between murderous acts is primary in the differentiation of serial, mass, and spree murderers", later elaborating that spree killers "will engage in the killing acts for days or weeks" while the "methods of murder and types of victims vary". Andrew Cunanan is given as an example of spree killing, while Charles Whitman is mentioned in connection with mass murder, and Jeffrey Dahmer with serial killing.[16]

In 2005, the FBI hosted a multi-disciplinary symposium in San Antonio, Texas, which brought together 135 experts on serial murder from a variety of fields and specialties with the goal of identifying the commonalities of knowledge regarding serial murder. The group also settled on a definition of serial murder which FBI investigators widely accept as their standard: "The unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same offender(s) in separate events".[15] Serial homicide researcher Enzo Yaksic found that the FBI was justified in lowering the victim threshold from three to two victims given that serial murderers from these groups share similar pathologies.[17]

History

[edit]

Early accounts

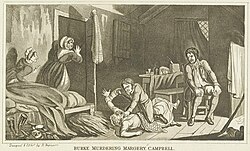

[edit]Historical criminologists suggest that there have been serial killers throughout history.[19] Some sources suggest that legends such as werewolves and vampires were inspired by medieval serial killers.[20] In Africa, there have been periodic outbreaks of murder by leopard men.[21]

Liu Pengli of China, nephew of the Han Emperor Jing, was made Prince of Jidong in the sixth year of the middle period of Jing's reign (144 BC). According to the Chinese historian Sima Qian, he would "go out on marauding expeditions with 20 or 30 slaves or with young men who were in hiding from the law, murdering people and seizing their belongings for sheer sport". Although many of his subjects knew about these murders, it was not until the 29th year of his reign that the son of one of his victims finally sent a report to the emperor. Eventually, it was discovered that he had murdered at least 100 people. The officials of the court requested that Liu Pengli be executed; however, the emperor could not bear to have his own nephew killed, so Liu Pengli was made a commoner and banished.[22]

In the 9th century (year 257 of the Islamic Calendar), "a strangler from Baghdad was apprehended. He had murdered a number of women and buried them in the house where he was living."[23]

Inside and outside the United States

[edit]The majority of documented serial killers were active in the United States.[24][25] In one study of serial homicide in South Africa, many patterns were similar to established patterns in the U.S., with some exceptions: no offenders were female, offenders were lower educated than in the U.S., and both victims and offenders were predominantly black.[26]

In the 15th century, one of the wealthiest men in Europe and a former companion-in-arms of Joan of Arc, Gilles de Rais, was alleged to have sexually assaulted and killed peasant children, mainly boys, whom he had abducted from the surrounding villages and had taken to his castle.[27] It is estimated that his victims numbered between 140 and 800.[28] Similarly, the Hungarian aristocrat Elizabeth Báthory, born into one of the wealthiest families in Transylvania, allegedly tortured and killed as many as 650 girls and young women before her arrest in 1610.[29]

Between 1564 and 1589, German farmer Peter Stumpp killed 14 children, including his own son. He also murdered two pregnant women and had an incestuous relationship with his daughter. Stumpp claimed to have been granted the ability to turn into a werewolf by the Devil. As punishment for his crimes, Stumpp was put on a torture wheel and executed. His head was later severed and put on a pole next to the figure of a wolf to scare other people away from claiming themselves werewolves too.[30]

Members of the Thuggee cult in India may have murdered a million people between 1740 and 1840.[31] Thug Behram, a member of the cult, may have murdered as many as 931 victims.[32] In his 1886 book, Psychopathia Sexualis, psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing noted a case of a serial murderer in the 1870s, a Frenchman named Eusebius Pieydagnelle who had a sexual obsession with blood and confessed to murdering six people.[33]

The unidentified killer Jack the Ripper, who has been called the first modern serial killer,[34] killed at least five women, and possibly more,[35] in London in 1888. He was the subject of a massive manhunt and investigation by the Metropolitan Police, during which many modern criminal investigation techniques were pioneered. A large team of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries, forensic material was collected and suspects were identified and traced.[36] Police surgeon Thomas Bond assembled one of the earliest character profiles of the offender.[37]

The Ripper murders also marked an important watershed in the treatment of crime by journalists.[38] While not the first serial killer in history, Jack the Ripper's case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy.[38] The dramatic murders of financially destitute women in the midst of the wealth of London focused the media's attention on the plight of the urban poor and gained coverage worldwide. Jack the Ripper has also been called the most infamous serial killer of all time, and his legend has spawned hundreds of theories on his real identity and many works of fiction.[39]

H. H. Holmes was a serial killer in the United States, responsible for the death of at least nine victims in the early 1890s. The case was one of the first involving a serial murderer that gained widespread notoriety and publicity through sensationalized accounts in William Randolph Hearst's newspapers. However, at the same time of the Holmes case, in France, Joseph Vacher became known as "The French Ripper" after killing and mutilating 11 women and children. He was executed in 1898 after confessing to his crimes.[40][41]

Another notable non-American serial killer is Pedro Lopez, a murderer from South America, who killed a minimum of 110 young girls between 1969 and 1980. However, he claims that the number is over 300. He was released from a mental facility in 1998 and his whereabouts are still unknown. He is commonly nicknamed the "Monster of the Andes". An additional non-American serial killer is Luis Garavito from Colombia. Garavito would kill and torture boys using various disguises. He murdered around 140 boys ranging in ages from 8 to 16. He would dump his victims' bodies in mass graves.[42]

Late 20th century

[edit]

The serial killing phenomenon in the United States was especially prominent from 1970 to 2000, which has been described as the "golden age of serial murder".[43] The cause of the spike in serial killings has been attributed to urbanization, which put people in close proximity and offered anonymity.[44] The number of active serial killers in the United States peaked in 1989 and has been steadily trending downward since, coinciding with an overall decrease in crime in the United States since that time. The decline in serial killers has no known single cause but is attributed to a number of factors.[45] Mike Aamodt, emeritus professor at Radford University in Virginia, attributes the decline in number of serial killings to less frequent use of parole, improved forensic technology, and people behaving more cautiously.[46] Causes for the general reduction in violent crime following the 1990s include increased incarceration in the United States, the end of the crack epidemic in the United States, and decreased lead exposure in early childhood.[47][48][49]

Characteristics

[edit]Some commonly found characteristics of serial killers include the following:

- They may exhibit varying degrees of mental illness or psychopathy, which may contribute to their homicidal behavior.[50]

- For example, someone who is mentally ill may have psychotic breaks that cause them to believe they are another person or are compelled to murder by other entities.[51]

- Psychopathic behavior that is consistent with traits common to some serial killers include sensation seeking, a lack of remorse or guilt, impulsivity, the need for control, and predatory behavior.[15] Psychopaths can seem 'normal' and often quite charming, a state of adaptation that psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley called the "mask of sanity".[52]

- Serial killers may be more likely to engage in fetishism, partialism or necrophilia, which are paraphilias that involve a strong tendency to experience the object of erotic interest almost as if it were a physical representation of the symbolized body. Individuals engage in paraphilias which are organized along a continuum; participating in varying levels of fantasy perhaps by focusing on body parts (partialism), symbolic objects which serve as physical extensions of the body (fetishism), or the anatomical physicality of the human body; specifically regarding its inner parts and sexual organs (one example being necrophilia).[53]

- A disproportionate number exhibit Macdonald triad predictors of future violent behavior:

- Many are fascinated with fire setting.[5]

- They are involved in sadistic activity; especially in children who have not reached sexual maturity, this activity may take the form of torturing animals.[5]

- More than 60 percent, or simply a large proportion, wet their beds beyond the age of 12.[54]

- Some were involved in petty crimes, such as fraud, theft, vandalism, or similar offenses.[55]

- Often, they have trouble staying employed and tend to work in menial jobs. The FBI, however, states, "Serial murderers often seem normal; have families and/or a steady job."[15]

- Studies have suggested that serial killers generally have an average or low-average IQ, although they are often described, and perceived, as possessing IQs in the above-average range.[15][56] A sample of 202 IQs of serial killers had a median IQ of 89.[57] Some organized serial killers have a slightly higher IQ score averaging a little bit over 99, where disorganized killers average just under 93 in theirs. The average IQ of serial killers is 94.7.[58]

There are exceptions to these criteria, however. For example, Harold Shipman was a successful professional (a General Practitioner working for the NHS). He was considered a pillar of the local community; he even won a professional award for a children's asthma clinic and was interviewed by Granada Television's World in Action on ITV.[59] Dennis Nilsen was an ex-soldier turned civil servant and trade unionist who had no previous criminal record when arrested. Neither was known to have exhibited many of the tell-tale signs.[60] Vlado Taneski, a crime reporter, was a career journalist who was caught after a series of articles he wrote gave clues that he had murdered people.[61] Russell Williams was a successful and respected career Royal Canadian Air Force Colonel who was convicted of murdering two women, along with fetish burglaries and rapes.[62]

Development

[edit]Many serial killers have faced similar problems in their childhood development.[63] Hickey's Trauma Control Model explains how early childhood trauma can set the child up for deviant behavior in adulthood; the child's environment (either their parents or society) is the dominant factor determining whether or not the child's behavior escalates into homicidal activity.[64]

Family, or lack thereof, is the most prominent part of a child's development because it is what the child can identify with on a regular basis.[65] "The serial killer is no different from any other individual who is instigated to seek approval from parents, sexual partners, or others."[66] This need for approval is what influences children to attempt to develop social relationships with their family and peers. "The quality of their attachments to parents and other members of the family is critical to how these children relate to and value other members of society."[67]

Wilson and Seaman (1990) conducted a study on incarcerated serial killers, and what they concluded was the most influential factor that contributed to their homicidal activity.[68] Almost all of the serial killers in the study had experienced some sort of environmental problems during their childhood, such as a broken home caused by divorce, or a lack of a parental figure to discipline the child. Nearly half of the serial killers had experienced some type of physical or sexual abuse, and more of them had experienced emotional neglect.[67]

When a parent has a drug or alcohol problem, the attention in the household is on the parents rather than the child. This neglect of the child leads to the lowering of their self-esteem and helps develop a fantasy world in which they are in control. Hickey's Trauma Control Model supports how parental neglect can facilitate deviant behavior, especially if the child sees substance abuse in action.[69] This then leads to disposition (the inability to attach), which can further lead to homicidal behavior, unless the child finds a way to develop substantial relationships and fight the label they receive. If a child receives no support from anyone, then they are unlikely to recover from the traumatic event in a positive way. As stated by E. E. Maccoby, "the family has continued to be seen as a major—perhaps the major—arena for socialization".[70]

Chromosomal makeup

[edit]There have been studies looking into the possibility that an abnormality with one's chromosomes could be the trigger for serial killers.[71] Two serial killers, Bobby Joe Long and Richard Speck, came to attention for reported chromosomal abnormalities. Long had an extra X chromosome.[72] Speck was erroneously reported to have an extra Y chromosome; in fact, his karyotype was performed twice and was normal each time.[73] While attempts have been made to link the XYY karyotype to violence, including serial murder, research has consistently found little or no association between violent criminal behaviour and an extra Y chromosome.[74]

Fantasy

[edit]Children who do not have the power to control the mistreatment they suffer sometimes create a new reality to which they can escape. This new reality becomes their fantasy that they have total control of and becomes part of their daily existence. In this fantasy world, their emotional development is guided and maintained. According to Garrison (1996), "the child becomes sociopathic because the normal development of the concepts of right and wrong and empathy towards others is retarded because the child's emotional and social development occurs within his self-centered fantasies. A person can do no wrong in his own world and the pain of others is of no consequence when the purpose of the fantasy world is to satisfy the needs of one person" (Garrison, 1996). Boundaries between fantasy and reality are lost and fantasies turn to dominance, control, sexual conquest, and violence, eventually leading to murder. Fantasy can lead to the first step in the process of a dissociative state, which, in the words of Stephen Giannangelo, "allows the serial killer to leave the stream of consciousness for what is, to him, a better place".[75]

Criminologist Jose Sanchez reports, "The young criminal you see today is more detached from his victim, more ready to hurt or kill. The lack of empathy for their victims among young criminals is just one symptom of a problem that afflicts the whole society."[65] Lorenzo Carcaterra, author of Gangster (2001), explains how potential criminals are labeled by society, which can then lead to their offspring also developing in the same way through the cycle of violence. The ability for serial killers to appreciate the mental life of others is severely compromised, presumably leading to their dehumanization of others.[76] This process may be considered an expression of the intersubjectivity associated with a cognitive deficit regarding the capability to make sharp distinctions between other people and inanimate objects. For these individuals, objects can appear to possess animistic or humanistic power while people are perceived as objects.[76] Before he was executed, serial killer Ted Bundy stated media violence and pornography had stimulated and increased his need to commit homicide, although this statement was made during last-ditch efforts to appeal his death sentence.[67]

Organized, disorganized, and mixed

[edit]

In the 1970s and 1980s, FBI profilers instigated a simple division of serial killers into "organized" and "disorganized"; that is, those who plan their crimes, and those who act on impulse.[77] The FBI's Crime Classification Manual now places serial killers into three categories: organized, disorganized, and mixed (i.e., offenders who exhibit organized and disorganized characteristics).[78][79] Some killers descend from organized to disorganized as their killings continue,[80] as in the case of psychological decompensation or overconfidence due to having evaded capture.

Organized serial killers often plan their crimes methodically, usually abducting victims, killing them in one place and disposing of them in another. They often lure the victims with ploys appealing to their sense of sympathy. Others specifically target prostitutes, who are likely to go voluntarily with a stranger. These killers maintain a high degree of control over the crime scene and usually have a solid knowledge of forensic science that enables them to cover their tracks, such as burying the body or weighing it down and sinking it in a river. They follow their crimes in the news media carefully and often take pride in their actions as if it were all a grand project.[81]

Often, organized killers have social and other interpersonal skills sufficient to enable them to develop both personal and romantic relationships, friends and lovers and sometimes even attract and maintain a spouse and sustain a family including children. Among serial killers, those of this type are in the event of their capture most likely to be described by acquaintances as kind and unlikely to hurt anyone. Ted Bundy and John Wayne Gacy are examples of organized serial killers.[81] In general, the IQs of organized serial killers tend to be normal range, with a mean of 98.7.[82]

Disorganized serial killers are usually far more impulsive, often committing their murders with a random weapon available at the time, and usually do not attempt to hide the body. They are likely to be unemployed, a loner, or both, with very few friends. They often turn out to have a history of mental illness, and their modus operandi (M.O.) or lack thereof is often marked by excessive violence and sometimes necrophilia or sexual violence.[83] Disorganized serial killers have been found to have a lower mean IQ than organized serial killers, at 89.4. Mixed serial killers, with both organized and disorganized traits, have an average IQ of 100.9, but a low sample size.[82]

Medical professionals

[edit]

Some people with a pathological interest in the power of life and death tend to be attracted to medical professions or acquiring such a job.[84] These kinds of killers are sometimes referred to as "angels of death"[85] or angels of mercy. Medical professionals will kill their patients for money, for a sense of sadistic pleasure, for a belief that they are "easing" the patient's pain, or simply "because they can".[86] Perhaps the most prolific of these was the British doctor Harold Shipman. Another such killer was nurse Jane Toppan, who admitted during her murder trial that she was sexually aroused by death.[87] She would administer a drug mixture to patients she chose as her victims, lie in bed with them and hold them close to her body as they died.[87]

Another medical professional serial killer is Genene Jones. It is believed she killed 11 to 46 infants and children while working at Bexar County Medical Center Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, United States.[88] She is currently serving a 99-year sentence for the murder of Chelsea McClellan and the attempted murder of Rolando Santos,[88] and became eligible for parole in 2017 due to a law in Texas at the time of her sentencing to reduce prison overcrowding.[88] A similar case occurred in Britain in 1991, where nurse Beverley Allitt killed four children at the hospital where she worked, attempted to kill three more, and injured a further six over the course of two months. A 21st-century example is Canadian nurse Elizabeth Wettlaufer, who murdered elderly patients in the nursing homes where she worked. William George Davis is another hospital nurse who was sentenced to death in Texas for the murder of four patients.[89]

Female

[edit]

Female serial killers are rare compared to their male counterparts.[91] Sources suggest that female serial killers represented less than one in every six known serial murderers in the United States between 1800 and 2004 (64 females from a total of 416 known offenders), or that around 15% of U.S. serial killers have been women, with a collective number of victims between 427 and 612.[92] The authors of Lethal Ladies, Amanda L. Farrell, Robert D. Keppel, and Victoria B. Titterington, state that "the Justice Department indicated 36 female serial killers have been active over the course of the last century."[93] According to The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, there is evidence that 16% of all serial killers are women.[94]

Michael D. Kelleher and C. L. Kelleher created several categories to describe female serial killers. They used the classifications of black widow, angel of death, sexual predator, revenge, profit or crime, team killer, question of sanity, unexplained, and unsolved. In using these categories, they observed that most women fell into the categories of the black widow or team killer.[95] Although motivations for female serial killers can include attention seeking, addiction, or the result of psychopathological behavioral factors,[96] female serial killers are commonly categorized as murdering men for material gain, usually being emotionally close to their victims,[91] and generally needing to have a relationship with the victim,[95] hence the traditional cultural image of the "black widow".

The methods that female serial killers use for murder are frequently covert or low-profile, such as murder by poison (the preferred choice for killing).[97] Other methods used by female serial killers include shootings (used by 20%), suffocation (16%), stabbing (11%), and drowning (5%).[96] They commit killings in specific places, such as their home or a health-care facility, or at different locations within the same city or state.[98] A notable exception to the typical characteristics of female serial killers is Aileen Wuornos,[99] who killed outdoors instead of at home, used a gun instead of poison, and killed strangers instead of friends or family.[100] One "analysis of 86 female serial killers from the United States found that the victims tended to be spouses, children or the elderly".[95] Other studies indicate that since 1975, increasingly strangers are marginally the most preferred victim of female serial killers,[101] or that only 26% of female serial killers kill for material gain only.[102] Sources state that each killer will have her own proclivities, needs and triggers.[103][95] A review of the published literature on female serial murder stated that "sexual or sadistic motives are believed to be extremely rare in female serial murderers, and psychopathic traits and histories of childhood abuse have been consistently reported in these women."[95]

A study by Eric W. Hickey (2010) of 64 female serial killers in the United States indicated that sexual activity was one of several motives in 10% of the cases, enjoyment in 11% and control in 14% and that 51% of all U.S. female serial killers murdered at least one woman and 31% murdered at least one child.[104] In other cases, women have been involved as an accomplice with a male serial killer as a part of a serial killing team.[103][95] A 2015 study published in The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology found that the most common motive for female serial killers was for financial gain and almost 40% of them had experienced some sort of mental illness.[105]

Peter Vronsky in Female Serial Killers (2007) maintains that female serial killers today often kill for the same reason males do: as a means of expressing rage and control. He suggests that sometimes the theft of the victims' property by the female "black widow" type serial killer appears to be for material gain, but really is akin to a male serial killer's collecting of totems (souvenirs) from the victim as a way of exerting continued control over the victim and reliving it.[106] By contrast, Hickey states that although popular perception sees "black widow" female serial killers as something of the Victorian past, in his statistical study of female serial killer cases reported in the United States since 1826, approximately 75% occurred since 1950.[107]

Elizabeth Báthory is sometimes cited as the most prolific female serial killer in all of history. Formally countess Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed (Báthory Erzsébet in Hungarian, August 7, 1560 – August 21, 1614), she was a countess from the Báthory family. Before her husband's death, Elizabeth took great pleasure in torturing the staff, by jamming pins under the servant's fingernails or stripping servants and throwing them into the snow.[108] After her husband's death, she and four collaborators were accused of torturing and killing hundreds of girls and young women, with one witness attributing to them over 600 victims, though the number for which they were convicted was 80. Elizabeth herself was neither tried nor convicted. In 1610, however, she was imprisoned in the Csejte Castle, where she remained bricked in a set of rooms until her death four years later.[109]

A 2010 article by Perri and Lichtenwald addressed some of the misconceptions concerning female criminality.[110] In the article, Perri and Lichtenwald analyze the current research regarding female psychopathy, including case studies of female psychopathic killers featuring Munchausen syndrome by proxy, cesarean section homicide, fraud detection homicide, female kill teams, and a female serial killer.[110]

Juvenile

[edit]Juvenile serial killers are rare. There are three main categories that juvenile serial killers can fit into: primary, maturing, and secondary killers. There have been studies done to compare and contrast these three groups and to discover similarities and differences between them.[111] Although these types of serial killers are less common, oftentimes adult serial killers may make their debut at an early age and it can be an opportunity for researchers to study what factors brought about the behavior. While juvenile serial killers are rare, the youngest felon on death row is a juvenile serial killer named Harvey Miguel Robinson who was 17 at the time of his crimes and 18 at the time of his arrest.[112][113]

Ethnicity and demographics in the United States

[edit]

There is a myth that all serial killers are white males.[15] However, according to the FBI, the racial composition of serial killers as a group reflects the racial composition of the overall U.S. population.[15] White males are actually greatly under-represented among serial killers in proportion to their overall numbers in the United States.[115] According to a 2016 study, since the year 2000, African Americans accounted for roughly 60% of all serial killers in the United States.[115]

Anthony Walsh has said that non-white serial killers are often ignored by the mainstream media. According to his analysis, Black males were over-represented among serial killers by a factor of 2, yet media coverage at that time overwhelmingly focused on white male serial killers.[116][117] Walsh argues that the popular media ignores black serial killers because there is a fear of allegations of racism. This may enable black serial killers to operate more effectively, as their crimes do not get the same media attention as the crimes of non-black serial killers.[117]

Motives

[edit]The motives of serial killers are generally placed into four categories: visionary, mission-oriented, hedonistic, and power or control; however, the motives of any given killer may display considerable overlap among these categories.[118]

Visionary

[edit]Visionary serial killers suffer from psychotic breaks with reality,[119] sometimes believing they are another person or are compelled to murder by entities such as the Devil or God.[120] The two most common subgroups are "demon mandated" and "God mandated".[51]

Herbert Mullin believed the American casualties in the Vietnam War were preventing California from experiencing the Big One. As the war wound down, Mullin claimed his father instructed him via telepathy to raise the number of "human sacrifices to nature" to delay a catastrophic earthquake that would plunge California into the ocean.[121] David Berkowitz ("Son of Sam") may also be an example of a visionary serial killer, having claimed a demon transmitted orders through his neighbor's dog and instructed him to commit murder.[122] Berkowitz later described those claims as a hoax, as originally concluded by psychiatrist David Abrahamsen.[123]

Mission-oriented

[edit]

Mission-oriented killers typically justify their acts as "ridding the world" of certain types of people perceived as undesirable, such as the homeless, ex-cons, homosexuals, drug users, prostitutes, or people of different ethnicity or religion; however, they are generally not psychotic.[124] Some see themselves as attempting to change society, often to cure a societal ill.[125]

An example of a mission-oriented killer would be Joseph Paul Franklin, an American white supremacist who exclusively targeted Jewish, biracial, and African American individuals for the purpose of inciting a "race war".[126][127] Saeed Hanaei was a serial killer convicted of murdering at least sixteen women in his native Iran, many of whom were sex workers. He reported his goal was to cleanse his city of "moral corruption" and that his mission was sanctioned by God.[128]

Hedonistic

[edit]This type of serial killer seeks thrills and derives pleasure and satisfaction from killing, seeing people as expendable means to this goal. Forensic psychologists have identified three subtypes of the hedonistic killer: "lust", "thrill", and "comfort".[129]

Lust

[edit]Sex is the primary motive of lust killers, whether or not the victims are dead, and fantasy plays a large role in their killings.[130] Their sexual gratification depends on the amount of torture and mutilation they perform on their victims. The sexual serial murderer has a psychological need to have absolute control, dominance, and power over their victims, and the infliction of torture, pain, and ultimately death is used in an attempt to fulfill their need.[131] They usually use weapons that require close contact with the victims, such as knives or hands. As lust killers continue with their murders, the time between killings decreases or the required level of stimulation increases, sometimes both.[132]

Kenneth Bianchi, one of the "Hillside Stranglers", murdered women and girls of different ages, races, and appearance because his sexual urges required different types of stimulation and increasing intensity.[133] Jeffrey Dahmer searched for his perfect fantasy lover—beautiful, submissive and eternal. As his desire increased, he experimented with drugs, alcohol, and exotic sex. His increasing need for stimulation was demonstrated by the dismemberment of victims, whose heads and genitals he preserved, and by his attempts to create a "living zombie" under his control (by pouring acid into a hole drilled into the victim's skull).[134]

Dahmer once said, "Lust played a big part of it. Control and lust. Once it happened the first time, it just seemed like it had control of my life from there on in. The killing was just a means to an end. That was the least satisfactory part. I didn't enjoy doing that. That's why I tried to create living zombies with acid and the drill." He further elaborated on this, also saying, "I wanted to see if it was possible to make—again, it sounds really gross—uh, zombies, people that would not have a will of their own, but would follow my instructions without resistance. So after that, I started using the drilling technique."[135] He experimented with cannibalism to "ensure his victims would always be a part of him".[136]

Thrill

[edit]

The primary motive of a thrill killer is to induce pain or terror in their victims, which provides stimulation and excitement for the killer.[130] They seek the adrenaline rush provided by hunting and killing victims. Thrill killers murder only for the kill; usually, the attack is not prolonged, and there is no sexual aspect. Usually, the victims are strangers, although the killer may have followed them for a period of time. Thrill killers can abstain from killing for long periods of time and become more successful at killing as they refine their murder methods. Many attempt to commit the perfect crime and believe they will not be caught.[138]

Robert Hansen took his victims to a secluded area, where he would let them loose and then hunt and kill them.[139] In one of his letters to San Francisco Bay Area newspapers in San Francisco, California, the Zodiac Killer wrote "[killing] gives me the most thrilling experience it is even better than getting your rocks off with a girl".[140] Carl Watts was described by a surviving victim as "excited and hyper and clappin' and just making noises like he was excited, that this was gonna be fun" during the 1982 attack.[141] Slashing, stabbing, hanging, drowning, asphyxiating, and strangling were among the ways Watts killed.[142]

Comfort (profit)

[edit]Material gain and a comfortable lifestyle are the primary motives of comfort killers.[143] Usually, the victims are family members and close acquaintances.[130] After a murder, a comfort killer will usually wait for a period of time before killing again to allow any suspicions by family or authorities to subside. They often use poison, most notably arsenic, to kill their victims. Female serial killers are often comfort killers, although not all comfort killers are female.[144]

Dorothea Puente killed her tenants for their Social Security checks and buried them in the backyard of her home.[145] H. H. Holmes killed for insurance and business profits.[146] Puente and Holmes had previous records of crimes such as theft, fraud, non-payment of debts, embezzlement and others of a similar nature. Dorothea Puente was finally arrested on a parole violation, having been on parole for a previous fraud conviction.[147] Contract killers ("hitmen") may exhibit similar characteristics of serial killers, but are generally not classified as such because of third-party killing objectives and detached financial and emotional incentives.[148][149][150] Nevertheless, there are occasionally individuals that are labeled as both a hitman and a serial killer.[151]

Power/control

[edit]

The main objective for this type of serial killer is to gain and exert power over their victim. Such killers are sometimes abused as children, leaving them with feelings of powerlessness and inadequacy as adults. Many power- or control-motivated killers sexually abuse their victims, but they differ from hedonistic killers in that rape is not motivated by lust (as it would be with a lust murder) but as simply another form of dominating the victim.[152] Ted Bundy is an example of a power/control-oriented serial killer. He traveled around the United States seeking women to control.[153]

Media influences

[edit]Many serial killers claim that a violent culture influenced them to commit murders. During his final interview, Ted Bundy stated that hardcore pornography was responsible for his actions. Others idolise figures for their deeds or perceived vigilante justice, such as Peter Kürten, who idolized Jack the Ripper, or John Wayne Gacy and Ed Kemper, who both idolized the actor John Wayne.[5]

Killers who have a strong desire for fame or to be renowned for their actions desire media attention as a way of validating and spreading their crimes; fear is also a component here, as some serial killers enjoy causing fear. An example is Dennis Rader, who sought attention from the press during his murder spree.[154]

Theories

[edit]Biological and sociological

[edit]Theories for why certain people commit serial murder have been advanced. Some theorists believe the reasons are biological, suggesting serial killers are born, not made, and that their violent behavior is a result of abnormal brain activity. Holmes believes that "until a reliable sample can be obtained and tested, there is no scientific statement that can be made concerning the exact role of biology as a determining factor of a serial killer personality."[155]

The "Fractured Identity Syndrome" (FIS) is a merging of Charles Cooley's "looking glass self" and Erving Goffman's "virtual" and "actual social identity" theories. The FIS suggests a social event, or series of events, during one's childhood results in a fracturing of the personality of the serial killer. The term "fracture" is defined as a small breakage of the personality which is often not visible to the outside world and is only felt by the killer.[156]

"Social Process Theory" has also been suggested as an explanation for serial murder. Social process theory states that offenders may turn to crime due to peer pressure, family and friends. Criminal behavior is a process of interaction with social institutions, in which everyone has the potential for criminal behavior. A lack of family structure and identity could also be a cause leading to serial murder traits. A child used as a scapegoat will be deprived of their capacity to feel guilt. Displaced anger could result in animal torture, as identified in the Macdonald triad, and a further lack of basic identity.[157]

Military

[edit]

The "military theory" has been proposed as an explanation for why serial murderers kill, as some serial murderers have served in the military or related fields. According to Castle and Hensley, 7% of the serial killers studied had military experience.[158] This figure may be a proportional under-representation when compared to the number of military veterans in a nation's total population. For example, according to the United States census for the year 2000, military veterans comprised 12.7% of the U.S. population;[159] in England, it was estimated in 2007 that military veterans comprised 9.1% of the population.[160] Though by contrast, about 2.5% of the population of Canada in 2006 consisted of military veterans.[161][162]

There are two theories that can be used to study the correlation between serial killing and military training: Applied learning theory states that serial killing can be learned. The military is training for higher kill rates from servicemen while training the soldiers to be desensitized to taking a human life.[163] Social learning theory can be used when soldiers get praised and accommodated for killing. They learn or believe that they learn, that it is acceptable to kill because they were praised for it in the military. Serial killers want accreditation for the work that they have done.[164]

In both military and serial killing, the offender or the soldier may become desensitized to killing as well as compartmentalized; the soldiers do not see enemy personnel as "human" and neither do serial killers see their victims as humans.[165] The theories do not imply that military institutions make a deliberate effort to produce serial killers; to the contrary, all military personnel are trained to recognize when, where, and against whom it is appropriate to use deadly force, which starts with the basic Law of Land Warfare, taught during the initial training phase, and may include more stringent policies for military personnel in law enforcement or security.[166]

Investigation

[edit]FBI: Issues and practices

[edit]In 2008, the FBI published a handbook titled Serial Murder which was the product of a symposium held in 2005 to bring together the many issues surrounding serial murder, including its investigation.[167]

Identification

[edit]

According to the FBI, identifying one, or multiple, murders as being the work of a serial killer is the first challenge an investigation faces, especially if the victim(s) come from a marginalized or high-risk population and is normally linked through forensic or behavioral evidence.[167] Should the cases cross multiple jurisdictions, the law enforcement system in the United States is fragmented and thus not configured to detect multiple similar murders across a large geographic area.[168] Ted Bundy was particularly famous for such geographic exploitations. He used his knowledge about the lack of communication between multiple jurisdictions to avoid arrest and detection.[169] The FBI suggests utilizing databases and increasing interdepartmental communication. Keppel suggests holding multi-jurisdictional conferences regularly to compare cases giving departments a greater chance to detect linked cases and overcome linkage blindness.[170]

One collaboration, the Serial Homicide Expertise and Information Sharing Collaborative, was formed in 2010 and made serial murder data widely accessible after multiple experts combined their databases to aid in research and investigation.[171] Another collaboration, the Radford/FGCU Serial Killer Database Project[172] was proposed at the 2012 FDIAI Annual Conference.[173] Utilizing Radford's Serial Killer Database as a starting point, the new collaboration,[174] hosted by FGCU Justice Studies, has invited and is working in conjunction with other universities to maintain and expand the scope of the database to also include spree and mass murders. Utilizing over 170 data points, multiple-murderer methodology and victimology; researchers and Law Enforcement Agencies can build case studies and statistical profiles to further research the Who, What, Why and How of these types of crimes.

Leadership

[edit]Leadership, or administration, should play a small or virtually non-existent role in the actual investigation past assigning knowledgeable or experienced homicide investigators to lead positions. The administration's role is not to run the investigation but to establish and reaffirm the primary goal of catching the serial killer, as well as provide support for the investigators. The FBI (2008) suggests completing Memorandums of Understanding to facilitate support and commitment of resources from different jurisdictions to an investigation.[167] Egger takes this one step further and suggests completing mutual aid pacts, which are written agreements to provide support to each other in a time of need, with surrounding jurisdictions. Doing this in advance would save time and resources that could be used on the investigation.[168]

Organization

[edit]

The structural organization of an investigation is key to its success, as demonstrated by the investigation of Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer. Once a serial murder case was established, a task force was created to track down and arrest the offender. Over the course of the investigation, for various reasons, the task force's organization was radically changed and reorganized multiple times – at one point including more than 50 full-time personnel, and at another, only a single investigator. Eventually, what led to the end of the investigation was a conference of 25 detectives organized to share ideas to solve the case.[175]

The FBI handbook provides a description of how a task force should be organized but offers no additional options on how to structure the investigation. While it appears advantageous to have a full-time staff assigned to a serial murder investigation, it can become prohibitively expensive. For example, the Green River Task Force cost upwards of $2 million per year,[175] and as was witnessed with the Green River Killer investigation, other strategies can prevail where a task force fails. A common strategy, already employed by many departments for other reasons, is the conference, in which departments get together and focus on a specific set of topics.[176] With serial murders, the focus is typically on unsolved cases, with evidence thought to be related to the case at hand.

Similar to a conference is an information clearing-house in which a jurisdiction with a suspected serial murder case collects all of its evidence and actively seeks data that may be related from other jurisdictions.[176] By collecting all of the related information into one place, they provide a central point in which it can be organized and easily accessed by other jurisdictions working toward the goal of arresting an offender and ending the murders. A task force provides for a flexible, organized, framework for jurisdictions depending on the needs of the investigation. Unfortunately due to the need to commit resources (manpower, money, equipment, etc.) for long periods of time it can be an unsustainable option.[176][167][170]

In the case of the investigation of Aileen Wournos, the Marion County Sheriff coordinated multiple agencies without any written or formal agreement.[168] While not a specific strategy for a serial murder investigation, this is certainly a best practice in so far as the agencies were able to work easily together toward a common goal. Finally, once a serial murder investigation has been identified, the use of an FBI Rapid Response Team can assist both experienced and inexperienced jurisdictions in setting up a task force. This is completed by organizing and delegating jobs, by compiling and analyzing clues, and by establishing communication between the parties involved.[168]

Resource augmentation

[edit]During the course of a serial murder investigation, it may become necessary to call in additional resources; the FBI defines this as Resource Augmentation. Within the structure of a task force, the addition of a resource should be thought of as either long-term or short-term. If the task force's framework is expanded to include the new resource, then it should be permanent and not removed. For short-term needs, such as setting up roadblocks or canvassing a neighborhood, additional resources should be called in on a short-term basis. The decision of whether resources are needed short or long term should be left to the lead investigator and facilitated by the administration.[167]

The confusion and counter productiveness created by changing the structure of a task force mid investigation is illustrated by the way the Green River Task Force's staffing and structure was changed multiple times throughout the investigation. This made an already complicated situation more difficult, resulting in the delay or loss of information, which allowed Ridgway to continue killing.[175] The FBI model does not take into account that permanently expanding a task force, or investigative structure, may not be possible due to cost or personnel availability. Egger (1998) offers several alternative strategies including; using investigative consultants, or experienced staff to augment an investigative team. Not all departments have investigators experienced in serial murder and by temporarily bringing in consultants, they can educate a department to a level of competence then step out. This would reduce the initially established framework of the investigation team and save the department the cost of retaining the consultants until the conclusion of the investigation.[168]

Communication

[edit]The FBI handbook (2008) and Keppel (1989) both stress communication as paramount. The difference is that the FBI handbook concentrates primarily on communication within a task force, while Keppel makes getting information out to and allowing information to be passed back from patrol officers a priority.[167][170] The FBI handbook suggests having daily e-mail or in-person briefings for all staff involved in the investigation and providing periodic summary briefings to patrol officers and managers. Looking back on a majority of serial murderer arrests, most are exercised by patrol officers in the course of their everyday duties and unrelated to the ongoing serial murder investigation.[168][170]

Keppel provides examples of Larry Eyler, who was arrested during a traffic stop for a parking violation, and Ted Bundy, who was arrested during a traffic stop for operating a stolen vehicle.[170] In each case, it was uniformed officers, not directly involved in the investigation, who knew what to look for and took the direct action that stopped the killer. By providing up-to-date (as opposed to periodic) briefings and information to officers on the street the chances of catching a serial killer, or finding solid leads, are increased.

Data management

[edit]A serial murder investigation generates staggering amounts of data, all of which needs to be reviewed and analyzed. A standardized method of documenting and distributing information must be established and investigators must be allowed time to complete reports while investigating leads and at the end of a shift (FBI 2008).[167] When the mechanism for data management is insufficient, leads are not only lost or buried but the investigation can be hindered and new information can become difficult to obtain or become corrupted.[175]

During the Green River Killer investigation, reporters would often find and interview possible victims or witnesses ahead of investigators. The understaffed investigation was unable to keep up the information flow, which prevented them from promptly responding to leads. To make matters worse, investigators believed that the journalists, untrained in interviewing victims or witnesses of crimes, would corrupt the information and result in unreliable leads.[175]

Memorabilia

[edit]Notorious and infamous serial killers number in the thousands and a subculture revolves around their legacies.[177] That subculture includes the collection, sale, and display of serial killer memorabilia, dubbed "murderabilia" by Andrew Kahan, one of the best-known opponents of collectors of serial killer remnants. Kahan is the director of the Mayor's Crime Victims Office in Houston. He is backed by the families of murder victims and "Son of Sam laws" existing in some states that prevent murderers from profiting from the publicity generated by their crimes.[178]

Such memorabilia includes the paintings, writings, and poems of these killers.[179] Recently, marketing has capitalized even more upon interest in serial killers with the rise of various merchandise such as trading cards, action figures, and books. Some serial killers attain celebrity status in the way they acquire fans and may have previous personal possessions auctioned off on websites like eBay. A few examples of this are Ed Gein's 150-pound stolen gravestone and Bobby Joe Long's sunglasses.[180]

See also

[edit]- Serial crime

- Serial rapist

- List of serial killers by country

- List of serial killers by number of victims

- List of songs about or referencing serial killers

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c An offender can be anyone:

- Holmes & Holmes 1998, Serial murder is the killing of three or more people over a period of more than 30 days, with a significant cooling-off period between the murders The baseline number of three victims appears to be most common among those who are the academic authorities in the field. The time frame also appears to be an agreed-upon component of the definition.

- Petherick 2005, p. 190 Three killings seem to be required in the most popular definition of serial killing since they are enough to provide a pattern within the killings without being overly restrictive.

- Flowers 2012, p. 195 In general, most experts on serial murder require that a minimum of three murders be committed at different times and usually different places for a person to qualify as a serial killer.

- Schechter 2012, p. 73 Most experts seem to agree, however, that to qualify as a serial killer, an individual has to slay a minimum of three unrelated victims.

- "Definition of Serial Murder". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved August 20, 2024. (This source only requires two people)

- ^ Burkhalter Chmelir 2003, p. 1, Morton 2005, pp. 4, 9

- ^ Morton 2005, pp. 4, 9.

- ^ a b c d Scott, Shirley Lynn. "What Makes Serial Killers Tick?". truTV. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Serial Murder". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Ressler & Schachtman 1993, p. 29, Schechter 2003, p. 5

- ^ Rule 2004, p. 225.

- ^ Gennat 1930, pp. 7, 27–32, 49–54, 79–82.

- ^ a b Vronsky 2004

- ^ "Review: The Meaning of Murder". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. May 30, 1967. p. 12, col. 4.

- ^ Vronsky 2013.

- ^ Petherick 2005, p. 190.

- ^ Flowers 2012, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morton 2005

- ^ Fuller, John R. & Hickey, Eric W.: Controversial Issues in Criminology; Allyn and Bacon, 1999. p. 36.

- ^ Yaksic, Enzo (November 1, 2018). "The folly of counting bodies: Using regression to transgress the state of serial murder classification systems". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 43: 26–32. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.08.007. ISSN 1359-1789.

- ^ Jarmo Haapalainen (2007). Twelve murders in five weeks, Heinola's "beast" Finnish record (in Finnish). Heinola. ISBN 978-952-99946-0-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ S. Waller (2011). Serial Killers – Philosophy for Everyone: Being and Killing. John Wiley & Sons. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4443-4140-9. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Schlesinger 2000, p. 5.

- ^ "Tanganyika: Murder by Lion". Time. November 4, 1957. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ Qian 1993, p. 387.

- ^ Al-Tabari. "Al-Tabari's History, vol. 36" (PDF). pp. 868–879 [123]. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Newton 2006, p. 95.

- ^ Dirk C. Gibson (2014). Serial Killers Around the World: The Global Dimensions of Serial Murder. Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-1-60805-842-6. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Salfati, Gabrielle; et al. (2015). "South African Serial Homicide: Offender and Victim Demographics and Crime Scene Actions" (PDF). Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 12: 18–43. doi:10.1002/jip.1425. ISSN 1544-4759. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ Vronsky 2004, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Vronsky 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Vronsky 2007, p. 78.

- ^ "2 of the Earliest Serial Killers in History". aezoutbailbonds.com. April 27, 2022. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Rubinstein 2004, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Newton 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Norder, Vanderlinden & Begg 2004.

- ^ "Jack The Ripper: The First Serial Killer". Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "Jack the Ripper | Identity, Facts, Victims, and Suspects | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Canter 1994, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Canter 1994, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Davenport-Hines 2004, Woods & Baddeley 2009, pp. 20, 52

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jack the Ripper – the most famous serial killer of all time". truTV. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "The Werewolf Syndrome: Compulsive Bestial Slaughterers. Vacher the Ripper". truTV. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ "French 'Ripper' Guillotined – Joseph Vacher, Who Murdered More Than a Score of Persons, Executed at Bourg-en-Bresse". The New York Times. January 1, 1899. p. 7. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ Urie, Chris. "9 serial killers from around the world you may not have heard of". Insider. Archived from the original on January 7, 2024. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Ehrlich, Brenna (February 10, 2021). "Why Were There So Many Serial Killers Between 1970 and 2000 – and Where Did They Go?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Martin, G. (2018). Crime, Media and Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 2-PT71. ISBN 978-1-317-36897-7. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Yaksic, Enzo; Allely, Clare; De Silva, Raneesha; Smith-Inglis, Melissa; Konikoff, Daniel; Ryan, Kori; Gordon, Dan; Denisov, Egor; Keatley, David A. (January 2019). Chan, Heng Choon (Oliver) (ed.). "Detecting a decline in serial homicide: Have we banished the devil from the details?". Cogent Social Sciences. 5 (1). doi:10.1080/23311886.2019.1678450. ISSN 2331-1886.

- ^ Taylor, David (September 15, 2018). "Are American serial killers a dying breed?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Levitt, Stephen (2004). "Understanding Why Crime Fell in the 1990s: Four Factors that Explain the Decline and Six that Do Not" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (1): 163–190. doi:10.1257/089533004773563485. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2005.

- ^ J. Sampson, Robert; S. Winter, Alix (May 2018). "Poisoned Development: Assessing Childhood Lead Exposure as a Cauase of Crime in a Birth Cohort Followed Through Adolescence: Lead Poisoning and Crime". Criminology. 56 (2): 269–301. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12171.

- ^ Reyes, Jessica Wolpaw (October 17, 2007). "Environmental Policy as Social Policy? The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime". The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 7 (1). doi:10.2202/1935-1682.1796. ISSN 1935-1682. Archived from the original on November 2, 2022. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Morton 2005, Skeem et al., pp. 95–162

- ^ a b Bartol & Bartol 2004, p. 145.

- ^ Cleckley, Hervey M. (1951). "The Mask of Sanity". Postgraduate Medicine. 9 (3): 193–197. doi:10.1080/00325481.1951.11694097. ISSN 0032-5481. PMID 14807904.

- ^ Silva, Leong & Ferrari 2004, p. 794.

- ^ Singer & Hensley 2004, pp. 48, 461–476.

- ^ Mount 2007, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Holloway, Lynette. Of Course There Are Black Serial Killers Archived October 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Root.

- ^ "Serial Killer IQ". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ^ "Serial Killers: Insane or Super Intelligent?". www.psychologytoday.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "UK | Harold Shipman: The killer doctor". BBC News. January 13, 2004. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ "CrimeLibrary.com/Serial Killers/Sexual Predators/Dennis Nilsen – Growing Up Alone – Crime Library on". Trutv.com. November 23, 1945. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Testorides, Konstantin (June 24, 2008). "'Serial murder' journalist commits suicide". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Mellor 2012.

- ^ Rod Plotnik; Haig Kouyoumdjian (2010). Introduction to Psychology. Cengage Learning. p. 509. ISBN 978-1-111-79100-1. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 2000, p. 107.

- ^ a b Tithecott 1997, p. 38.

- ^ Hale 1993, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Hasselt 1999, p. 162.

- ^ Wilson & Seaman 1992.

- ^ Hickey 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Maccoby 1992, pp. 1006–1017.

- ^ Berit Brogaard, D.M.Sci., Ph.D (2018). "Do All Serial Killers Have a Genetic Predisposition to Kill? – Exploring a Complex Question". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "Shame and the Serial Killer: Humiliation's influence on criminal behavior needs more attention". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Engel, Eric (September 1972). "The making of an XYY". Am J Ment Defic. 77 (2): 123–7. PMID 5081078.

- ^ Robinson, Arthur; Lubs, Herbert A.; Bergsma, Daniel, eds. (1979). Sex chromosome aneuploidy: prospective studies on children. Birth defects original article series 15 (1). New York: Alan R. Liss. ISBN 978-0-8451-1024-9.

- Stewart, Donald A., ed. (1982). Children with sex chromosome aneuploidy: follow-up studies. Birth defects original article series 18 (4). New York: Alan R. Liss. ISBN 978-0-8451-1052-2.

- Ratcliffe, Shirley G.; Paul, Natalie, eds. (1986). Prospective studies on children with sex chromosome aneuploidy. Birth defects original article series 22 (3). New York: Alan R. Liss. ISBN 978-0-8451-1062-1.

- Evans, Jane A.; Hamerton, John L.; Robinson, Arthur, eds. (1991). Children and young adults with sex chromosome aneuploidy: follow-up, clinical and molecular studies. Birth defects original article series 26 (4). New York: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 978-0-471-56846-9.

- ^ Giannangelo 1996, p. 33.

- ^ a b Silva, Leong & Ferrari 2004, p. 790, Tithecott 1997, p. 43

- ^ Cotter, P. (2010). "The path to extreme violence: Nazism and serial killers". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 3 61: 1–5. doi:10.3389/neuro.08.061.2009. PMC 2813721. PMID 20126638.

- ^ Vronsky 2004, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Joshua A. Perper; Stephen J. Cina (2010). When Doctors Kill: Who, Why, and How. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-4419-1371-5. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Dennis L. Peck; Norman Dolch; Norman Allan Dolch (2001). Extraordinary Behavior: A Case Study Approach to Understanding Social Problems. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-275-97057-4. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Ressler & Schachtman 1993, p. 113.

- ^ a b "Serial Killer Statistics". Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Serial Killers". Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ Hickey 2010, p. 142

- ^ Wires, Linda (2015). "Angels of Death". New Scientist. 225 (3007): 40–43. Bibcode:2015NewSc.225...40W. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(15)60268-8. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 1998, p. 204.

- ^ a b Ramsland, Katherine (March 22, 2007). "When Women Kill Together". The Forensic Examiner. American College of Forensic Examiners Institute. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Genene Jones Biography". Archived from the original on June 3, 2012.

- ^ "Murder in the ICU: Inside the Twisted Case of a Hospital Nurse Who Turned Out To Be a Serial Killer". Peoplemag. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ "Most prolific murder partnership". Guinness World Records. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Kelleher & Kelleher 1998, p. 12, Wilson & Hilton 1998, pp. 495–498, Frei et al. 2006, pp. 167–176

- ^ Hickey 2010, pp. 187, 257, 266, Vronsky 2007, p. 9, Farrell, Keppel & Titterington 2011, pp. 228–252

- ^ Farrell, Keppel & Titterington 2011, pp. 228–252

- ^ Newton 2006

- ^ a b c d e f Frei et al. 2006, pp. 167–176

- ^ a b Educated attempt to provide specific information about a certain type of suspect. Department of Psychology, Concordia University. 2008. Archived from the original (PPT) on April 26, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Wilson & Hilton 1998, pp. 495–498, Frei et al. 2006, pp. 167–176, Holmes & Holmes 1998, p. 171, Newton 2006

- ^ Vronsky 2007, pp. 1, 42–43, Schechter 2003, p. 312

- ^ Schechter 2003, p. 31, Fox & Levin 2005, p. 117

- ^ Schmid 2005, p. 231, Arrigo & Griffin 2004, pp. 375–393

- ^ Vronsky 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Hickey 2010, p. 267.

- ^ a b Wilson & Hilton 1998, pp. 495–498

- ^ Hickey 2010, p. 265.

- ^ Harrison et al., pp. 383–406.

- ^ Vronsky 2007.

- ^ Eric W. Hickey, (2010).

- ^ Yardley & Wilson 2015, pp. 1–26.

- ^ Vronsky 2007, p. 73.

- ^ a b Perri & Lichtenwald 2010, pp. 50–67

- ^ Kirby 2009.

- ^ "Youngest Serial Killer on Death Row". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ "Harvey Robinson". National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Murderers. January 21, 2021. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Lowery, Wesley; Knowles, Hannah; Berman, Mark (November 30, 2020). "How America's deadliest serial killer went undetected for four decades". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Indifferent Justice Part 1: The Perfect Victim

- ^ a b Walsh, A.; Jorgensen, C. (2019). Criminology: The Essentials. Sage Publications. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-5443-7539-7. Retrieved May 21, 2024. "The reality is that white males are very much underrepresented among serial killers in proportion to their numbers in the population. Hickey (2006) claims that about 44% of serial killers operating from 1995 to 2004 have been African American, which is about 3.4 times greater than expected by the proportion of African Americans in the population. More recently, the Radford University's Serial Killer Information Center (Aamodt, 2016) found that since 2000 African Americans have been 59.8% of serial killers in the United States, whites 30.8%, Hispanics 6.7%, and Asian Americans 0.1%."

- ^ Walsh, Anthony (November 28, 2011). "African Americans and Serial Killing in the Media: The Myth and the Reality". Homicide Studies. Retrieved May 21, 2024. "There were many expressions of shock and surprise voiced in the media in 2002 when the “D.C. Sniper” turned out to be two Black males. Two of the stereotypes surrounding serial killers are that they are almost always White males and that African American males are barely represented in their ranks. In a sample of 413 serial killers operating in the United States from 1945 to mid-2004, it was found that 90 were African American. Relative to the African American proportion of the population across that time period, African Americans were overrepresented in the ranks of serial killers by a factor of about 2...The myth that serial killers are rarely African-Americans has had two detrimental effects. First, Whites tend to argue that Blacks are not sufficiently psychologically complex or intelligent to commit a series of murders without being caught. Second, police tend to neglect the protection of potential victims of serial killers in African-American communities. 1 table, 4 notes, and 64 references"

- ^ a b Walsh 2005, pp. 271–291.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 1998, pp. 43–44, Bartol & Bartol 2004, p. 284

- ^ Scott Bonn (2014). Why We Love Serial Killers: The Curious Appeal of the World's Most Savage Murderers. Skyhorse. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-63220-189-8. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 1998, p. 62.

- ^ Ressler & Schachtman 1993, p. 146.

- ^ Schechter 2003, p. 291.

- ^ Abrahamsen, David (July 1, 1979). "The Demons of 'Son of Sam'". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Vol. 101, no. 168. pp. 2G, 5G. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Scott, Jason (February 18, 2020). "'The worst serial killer I ever dealt with': The confession of Joseph Paul Franklin". www.fox19.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Understanding Pragmatic Mission Killers". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Ramsey, Nancy (May 25, 2004). "Out of Iran, a chilling truth". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ Bartol & Bartol 2004, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Curt R. Bartol; Anne M. Bartol (2008). Introduction to Forensic Psychology: Research and Application. Sage. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-1-4129-5830-1. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Myers et al. 1993, pp. 435–451.

- ^ Bartol & Bartol 2004, p. 146, Holmes & Holmes 2001, p. 163, Dobbert 2004, pp. 10–11

- ^ Dobbert 2004, p. 10-11.

- ^ Giannangelo 2012, Fulero & Wrightsman 2008, Dvorchak & Holewa 1991

- ^ MacCormick 2003, p. 431.

- ^ Dobbert 2004, p. 11.

- ^ "Vankilasta paenneen sarjakuristajan rikoshistoria on poikkeuksellisen synkkä". Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). October 14, 2015. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Bartol & Bartol 2004, p. 146, Howard & Smith 2004, p. 4

- ^ Howard & Smith 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Graysmith 2007, pp. 54–55.

- ^ "A Deal With the Devil?". 60 Minutes. October 14, 2004. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Mitchell 2006, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Curt R. Bartol; Anne M. Bartol (2012). Criminal & Behavioral Profiling. Sage Publications. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-1-4522-8908-3. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Bartol & Bartol 2004, p. 146, Schlesinger 2000, p. 276, Holmes & Holmes 2000, p. 41

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 2000, p. 43.

- ^ "Dorothea Puente, Killing for Profit – Easy Money". Trutv.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Zagros Madjd-Sadjadi (2013). The Economics of Crime. Business Expert Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-60649-583-4. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 1998, p. 7.

- ^ David Wilson; Elizabeth Yardley; Adam Lynes (2015). Serial Killers and the Phenomenon of Serial Murder: A Student Textbook. Waterside Press – Drew University. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-909976-21-4. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ David Wilson; Elizabeth Yardley; Adam Lynes (2015). Serial Killers and the Phenomenon of Serial Murder: A Student Textbook. Waterside Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-909976-21-4. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Egger, Steven A. (2000). "Why Serial Murderers Kill: An Overview". Contemporary Issues Companion: Serial Killers.

- ^ Peck & Dolche 2000, p. 255.

- ^ "Dennis Rader". Biography. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on March 18, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ Holmes & Holmes 2010, pp. 55–56.

- ^ "Serial Killers". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ Claus & Lindberg 1999, pp. 427–435.

- ^ Castle & Hensley 2002, pp. 453–465, DeFronzo & Prochnow 2004, pp. 104–108

- ^ Richardson, Christy; Waldrop, Judith (2003). "Veterans: 2000" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Woodhead et al. 2009, pp. 50–54.

- ^ "Estimated population of Canada, 1605 to present". Statistics Canada. July 6, 2009. Archived from the original on June 30, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "The Veteran Population and the People We Serve". Veterans Affairs Canada. 2003. Archived from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Castle & Hensley 2002.

- ^ "Social Learning and Serial Murder". www.deviantcrimes.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Hamamoto 2002, pp. 105–120.

- ^ Atwood 1992.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Serial Murder". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Egger 2002

- ^ Sanchez, Shanell. "1.1 Crime and the Criminal Justice System". Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System. Open Oregon Educational Resources. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Keppel 2000

- ^ Boyne, E. Serial Homicide Collaborative Brings Research Data Together. CJ Update: A Newsletter for Criminal Justice Educators. Retrieved from https://tandfbis.s3.amazonaws.com/rt-files/docs/SBU3/Criminology/CJ%20UPDATE%20FallWinter%202014.pdf

- ^ Elink-Schuurman-Laura, Kristin. "Radford/FGCU Serial Killer Database Project – Justice Studies FGCU". FGCU Department of Justice Studies. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ "FDIAI 52nd Annual Conference". Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ Aamodt, Mike. "Serial Killer Statistics" (PDF). Radford University. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Guillen 2007

- ^ a b c Egger 1990

- ^ "Getting away with murder". minotdailynews.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine; Karen Pepper. "Serial Killer Culture". Tru.tv Crime Library. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Bryan (January 7, 2006). "Serial Killer Action Figures For Sale". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine; Karen Pepper. "Serial Killer Culture". Tru.tv Crime Library. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Arrigo, B.; Griffin, A. (2004). "Serial Murder and the Case of Aileen Wuornos: Attachment Theory, Psychopathy, and Predatory Aggression". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 22 (3): 375–393. doi:10.1002/bsl.583. PMID 15211558.

- Atwood, Donald J. (February 25, 1992). "Department of Defense Directive AD-A272 176: Use of Deadly Force and the Carrying of Firearms by DoD Personnel Engaged in Law Enforcement and Security Duties" (PDF). DoD. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- Bartol, Curt R.; Bartol, Anne M. (2004). Introduction to Forensic Psychology: Research and Application. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-5830-1. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Brown, Pat (2008). Killing for Sport: Inside the Minds of Serial Killers. Phoenix Books, Inc. ISBN 9781597775755.