Wormsloe Plantation | |

| |

| Nearest city | Savannah, Georgia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°57′53″N 81°4′14″W / 31.96472°N 81.07056°W |

| Built | 1739 |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000615[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 26, 1973 |

The Wormsloe State Historic Site, originally known as Wormsloe Plantation, is a state historic site near Savannah, Georgia, in the southeastern United States. The site consists of 822 acres (3.33 km2), protecting part of what was once the Wormsloe Plantation, a large estate established by one of the founders of colonial Georgia, Noble Jones. The site includes a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) dirt road lined with southern live oaks, the ruins of a small house with fortified walls built of tabby,[2] a museum, and an area with recreations of colonial structures such as a blacksmithing forge and a house similar to those first built in the colony of Georgia (or as housing for enslaved people).

In 1736, Jones obtained a grant for 500 acres (2.0 km2) of land on the Isle of Hope which would form the core of Wormsloe. He constructed a fortified house on the southeastern tip of the island overlooking the Skidaway Narrows, a strategic section of the Skidaway River, located along the Intracoastal Waterway roughly halfway between downtown Savannah and the Atlantic Ocean. The fortified house was part of a network of defensive structures established by James Oglethorpe, founder of Georgia, and early Georgia colonists to protect Savannah from a potential Spanish invasion. Jones subsequently developed Wormsloe into a small plantation, and his descendants eventually had a large house, a library, slave housing, and a family cemetery built on the property.

The State of Georgia acquired the bulk of the Wormsloe Plantation in 1973 after a lengthy court battle over taxes which eventually was heard by the supreme court of Georgia.[3] The state opened the land to the public in 1979. The Barrow family (descendants of Noble Jones) retained a portion of the land including the historical house, slave quarters building, library, and family cemetery. According to the agreement with the state of Georgia, the descendants must reside on the premises as their primary residence otherwise the property rights will revert to the state.[3]

Geographic setting

[edit]

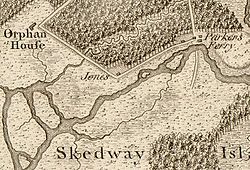

The Isle of Hope is an island (or peninsula, depending on the salt marsh water levels) situated approximately 11 miles (18 km) southeast of downtown Savannah in Georgia's Lower Coastal Plain. The island stretches for approximately 4 miles (6.4 km) from its northern tip to its southern tip and for roughly 2 miles (3.2 km) from its eastern shore to its western shore. The Skidaway River, which is part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, forms the island's eastern shore. The island's southwest shore is formed by the Moon River, the same Moon River that Johnny Mercer sings about in Moon River, and the island's northwest shore formed by the Herb River. Typical of Georgia's inshore coastal islands, the Isle of Hope is completely surrounded by a saltwater tidal marsh.[4] Skidaway Island is located opposite the Skidaway River to the east and the Georgia mainland is located opposite the Moon River to the west. Wormsloe occupies most of the southern half of the Isle of Hope.

A small island, known as Long Island, lies between Skidaway Island and the Isle of Hope and splits the Skidaway River into two narrow channels, the main (navigable) channel of which is known as the Skidaway Narrows. The main channel of the Skidaway River presently flows between Long Island and Skidaway Island, although in colonial times the main channel flowed between Long Island and the Isle of Hope, giving Wormsloe its historically strategic importance. When traveling by water, the Isle of Hope is just over 10 miles (16 km) from the Atlantic Ocean (via the Skidaway, Vernon, and Ogeechee rivers) to the southeast and just over 10 miles (16 km) from the Port of Savannah (via the Skidaway, Wilmington, and Savannah rivers) to the northwest.

Skidaway Road connects Wormsloe and the Isle of Hope to U.S. Route 80 near downtown Savannah. The Isle of Hope is located entirely within Chatham County, Georgia. Wormsloe Historic Site is managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

Native Americans have inhabited the Isle of Hope on at least a semi-annual basis for thousands of years, as indicated by oyster shell deposits excavated in the vicinity.

Evidence of human settlements dating back to 13000 BCE has been found in the land around Wormsloe Plantation including tools and materials used by Paleo-Indians.[5] The Bilbo mounds, large man-made earthen mounds found in Savannah GA, were built by ancient mound builders and construction has been dated back to around 3545 BCE and are currently the oldest man made structures in North America.[6]

The first Europeans to the area were Spanish Catholic missionaries who followed groups of migrating native Americans as they moved with the seasons, ca. 1500-1650.[5] The only attempt at a permanent settlement by Spanish colonists was in 1526 and it lasted only 6 weeks. The Spanish did establish settlements and missions in areas of Florida, but none near Wormsloe.[5] By the time colonists from South Carolina began exploring south, in the 16th century, the Isle of Hope was occupied by multiple communities of native Americans. The Westo traded with South Carolinians (just as they previously did with Virginians), often trading enslaved Indians for firearms. The Yamacraw and La Tama both had significant communities near Savannah in the 17-18th centuries. For many years the Westo were believed to be related to the Yuchi peoples but scholarship in the 20th century uncovered evidence to the contrary. [7]

In the early 1730s, the English decided to colonize the islands between the South Carolina and Florida to create a buffer area between Spanish and English territories. A charter for the Province of Georgia was granted in 1732 to be led by James Oglethorpe, and the first colonists set sail in the same year. The English colonists that arrived at Savannah in 1733 formed the core of what would eventually become the state of Georgia. Among them was Noble Jones, a physician and carpenter from Lambeth, England, who made the Transatlantic crossing with his wife and one child, Jones was apparently a loose acquaintance of Oglethorpe, and just before the colonists set sail from England, the colony's Trustees made Jones one of the settlement's lead officials. Like the other first settlers, Jones received a town lot in Savannah and a small farm on the outskirts of the town.[8]

When the first permanent English colonists landed at what is now Savannah in 1733, the Yamacraw, a detached branch of the Muscogee, were living in an area of Savannah called Yamacraw Bluff. James Oglethorpe maintained a friendly relationship with the Yamacraw Chief Tomochichi, and managed to acquire the Savannah area and the lands in its vicinity.[9]

Establishment of Wormsloe

[edit]

Noble Jones applied for a lease for 500 acres (2.0 km2) on the south side of the Isle of Hope in 1736 (the Trustees did not approve the lease until 1745) and began building a fortified house overlooking the Skidaway Narrows. The house was constructed between 1739 and 1745 using wood and tabby, a crude type of concrete made from oyster shells and lime. The fortress consisted of 8-foot (2.4 m) high walls with bastions at each of its four corners. The fort house was 1.5 stories and had five small rooms. Oglethorpe allotted Jones' fort a 12-man marine garrison and a scout boat with which to patrol the river.[9][10][11] "Wormslow"—the name Jones gave to his Isle of Hope estate—probably refers to Wormslow Hundred, Herefordshire, in the Welsh border country from which the Jones family hailed. Some historians suggest the name refers to Jones's attempts to cultivate silkworms at the plantation, but as his son Noble Wimberly Jones named his plantation "Lambeth", after his birthplace on the south bank of the River Thames, the former theory is more likely.[12]

Noble Jones's fortified house was one of several defensive works built between Frederica on Saint Simons Island and the Savannah townsite. The English were concerned that the Spanish still claimed the area and would eventually attempt to expel them. Conflict erupted in 1739 with the outbreak of the War of Jenkins' Ear, the name for the regional theater of the greater War of the Austrian Succession. Jones took part in an English raid along the St. Johns River in northern Florida in 1740, as well as the successful defense of Frederica at the Battle of Bloody Marsh in 1742.[13] The end of the war in 1748 largely neutralized Spanish threats to the new colony.

The War of Jenkins' Ear is commemorated annually on the last Saturday in May at Wormsloe Plantation.[14]

Antebellum Wormsloe

[edit]The owning of enslaved people had been banned by Georgia's original charter but Georgia settlers immediately began lobbying for the law to be overturned, arguing that it would be , “impossible for settlers to prosper without enslaved workers.”[15] Georgia settlers largely supported slavery and South Carolinians supported their rebellion by renting enslaved people to the settlers in Georgia, which was not technically illegal under Georgia laws.[16] Noble Jones used rented enslaved people to build his fortified house and to tend the land on Wormsloe in the plantation's early years. Some additional projects that were completed by enslaved people include clearing the heavily forested land, planting, tending and harvesting a large variety of crops, and digging a complex system of drainage ditches which still remain on the property. When the Trustees revoked the ban on slavery in 1749, Jones purchased enslaved people and from then until the civil war, Wormsloe had more than 1,500 enslaved people working on the property.

Wormsloe’s initial experiments with growing fruit trees, mulberry, and indigo did not succeed. Jones also imported 100 head of cattle from South Carolina.[17] The Georgia Trustees encouraged the production of silk and Jones planted many mulberry trees but the experiment was unsuccessful. While Wormsloe never proved profitable, Noble Jones purchased land and worked as a surveyor in the colony. Included in the real estate he acquired throughout his lifetime, were over 5,500 acres (22 km2) and five town lots in the Savannah area. In addition to surveyor, he served the colony in multiple capacities, as judge, militia captain, and colonial legislator.[18]

With the death of Noble Jones in 1775, Wormsloe passed to his daughter, Mary Jones Bulloch. Jones' death occurred just as the American colonies were on the verge of breaking away from England. Jones remained a loyal supporter of King George III throughout his life, a stance that often brought him in direct conflict with his son, Noble Wimberly Jones, who was an ardent supporter of Patriot causes. Noble Wimberly led the Georgia Commons House in its rejection of the Townshend Acts in 1768, and took part in a mission that seized a large supply of gunpowder from the provincial powder magazine in 1776.[19] Noble Jones' will stipulated that the Wormsloe plantation should be passed down to his daughter, Mary. According to Noble Jones’s will, after the death of Mary, Wormsloe passed to Noble Wimberly Jones and instructed for Wormsloe to pass , “thence to Noble Wimberly's heirs forever.” Thus Noble Wimberly inherited Wormsloe in 1795 upon the death of his sister. Noble Wymberly Jones lived at Wormsloe in his childhood and adolescence but didn’t return to the property as his primary residence.[20] He eventually deeded the plantation to his son George Jones in 1804.[21]

George Jones served as a U.S. senator and in various capacities in the Savannah government. He built a new, elaborate house at Wormsloe in 1828, which is still standing and has undergone multiple design renovations. He also focused the property’s business on cotton production through the forced labor of enslaved people and introducing steam engines to the process. He also was responsible for the majority of the familial wealth which was grown through his decisions. “His estate was appraised at $123,000, including some nine thousand acres of land and one hundred and thirty-seven slaves.”[20]

George Jones's son, George Frederick Tilghman Jones, inherited Wormsloe in 1857. Jones took an active interest in Wormsloe (he changed the spelling from "Wormslow" to "Wormsloe"), enlarging the plantation's gardens, adding the first oak-lined avenue, building a library and expanding the house. He changed his name to George Wymberley Jones De Renne (a corruption of his grandmother's maiden name, Van Deren). He began publishing a periodical collection of rare early Georgia documents under the title, the Wormsloe Quartos.[22] Under his direction, eight simple frame slave houses were built during his agricultural improvement campaign of the 1850s. Jones arranged the new cabins in a double row roughly halfway between the mansion house and the historic fort, with an overseer’s house located at the northern end of the slave village. These slave houses existed at the edge of the plantation’s work and wild spaces. Wormsloe’s slaves lived next to the quarters field and in close proximity to the old fort field and the Jones mansion. Their homes also bordered the rich estuarial marsh of the Skidaway River and the mixed pine and hardwood forest that covered much of the southern end of the Isle of Hope peninsula. Each cabin was surrounded by a paling fence that enclosed a kitchen gardenand a few chickens. Slaves labored in the cotton fields and farm buildings most mornings and early afternoons, and hunted, fished, and tended their own small gardens in the evenings and on Sundays.[23]

The civil war and after

[edit]During the American Civil War, the owners of Wormsloe (Jones/De Renne family) fled to Europe and various northern states. In their absence, Wormsloe and the Isle of Hope were fortified by Confederate forces. When Union forces captured Savannah in 1864, the plantation was confiscated by the U.S. government (it seized the property of planters who had supported the Confederacy). George Wymberly Jones De Renne applied for a pardon and it was granted by President Andrew Johnson. The property was eventually returned to the family, and at the time of his death, George Wymberly Jones Derenne was the richest man in Savannah with an estate valued at over $700,000.[20]

Following Emancipation, some of the liberated enslaved people continued to live in the plantation’s cabins and farm the land, first as sharecroppers and then as renters and wage laborers.[23] In their absence late 19th century, De Renne started a commercial dairy on Wormsloe. A grain silo is still visible on the family’s private property, from the oak avenue, dating to this endeavor. The grounds were also landscaped in the style of an ornate English garden which was opened as a public tourist attraction.

Wormsloe in the 20th century

[edit]In his will, George Wymberley Jones De Renne entrusted Wormsloe to the Pennsylvania Company until the death of his son, Wymberley Jones De Renne, at which time the estate would pass to his grandchildren. Wymberley Jones De Renne spent much time in Europe and traveling abroad until he returned to Wormsloe in 1893.While he lived at Wormsloe, he further expanded the gardens and planted a new oak avenue (still in use) lined with over 400 oak trees. He continued his father's contributions to history and tradition, publishing several works for the Georgia Historical Society and constructing the De Renne Georgia Library. Upon his death in 1916, Wormsloe passed to the grandchildren of George Wymberley Jones De Renne. In 1917, one grandson, Wymberley Wormsloe De Renne, bought his cousins' shares of the plantation.[24]

During the early twentieth century the De Renne family dismantled all of the cabins save one and used the salvaged materials in other construction project.[23] The remaining slave cabin was refurbished in 1929 and the De Rennes hired a local black woman named Liza to play the part of “a nice old-fashioned mammy.”[17] Adding to the attempts at “authenticity” of the display, Liza claimed that she had been born into slavery in the very same cabin. As tourists strolled through the azaleas, roses, and camellias they could pause at Liza’s cabin to enjoy Old South staples—coffee and hoecakes”—cooked by Liza.[17]

In 1938, poor real estate investments and the economic tumult of the Great Depression forced Wymberley and Augusta to relinquish Wormsloe to Wymberly sister, Elfrida De Renne Barrow. She assumed her brother Wymberley's debts, and eventually made the plantation her official residence. Elfrida Barrow created the Wormsloe Foundation, which continued and expanded the family tradition of publishing works related to Georgia history.

In 1961, Barrow donated most of the Wormsloe estate to the Wormsloe Foundation, while retaining ownership of Wormsloe House and approximately 50 acres of the surrounding area. In 1972, after the Wormsloe Foundation's tax-exempt status was revoked by the Supreme Court of Georgia, the foundation transferred ownership of Wormsloe to the Nature Conservancy, which in turn transferred it to the State of Georgia the following year. In 1979, the state opened the site to the public as Wormsloe State Historic Site. In the transfer of land ownership, the state allows the descendants of Noble Jones to remain in the family’s original house and maintain control of 50 acres of land surrounding the house. Those 50 acres include the large house, slave quarters, a library, a family cemetery, and multiple newer buildings. The family must continue living in the house as their primary residence otherwise the property rights will revert back into state control.[22]

Wormsloe Historic Site

[edit]The arched entrance to Wormsloe is located just off Skidaway Road, near the Isle of Hope community. The state-controlled area includes the scenic oak-lined avenue, a museum, and a walking trail that leads through the dense maritime forest to the ruins of the tabby fort built by Jones in 1745. More recently, the park has established a colonial life demonstration area, which includes a replica wattle and daub hut and several small outbuildings that simulate a living area for Jones' marines and slaves.

The Wormsloe site is within a dense oak-pine maritime forest. Much of the forest originally pre-dated European settlement of the Isle of Hope, but a southern pine beetle infestation in the 1970s killed off most of the old-growth pines. A short interpretive trail near the museum displays prints of wildlife and birds by the 18th-century naturalist Mark Catesby.

Wormsloe burial ground

[edit]In 1875, five years before his death, George Wymberley Jones De Renne erected a tombstone in the grounds of the estate to mark the burial location of his ancestors. The inscription reads: "George Wymberley Jones De Renne hath laid this stone MDCCCLXXV to mark old burial place of Wormsloe, 1737–1789, and to save from oblivion the graves of his kindred."[25] Known burials at the location include James Bulloch and his wife Jean; Sarah Jones, wife of Noble Jones, and their son Inigo; George Wymberley De Renne's daughter Elfrida De Renne Barrow, her husband Craig, their son Craig Jr. and Craig Jr.'s wife Laura Palmer Bell.[26]

-

Oak avenue in winter, built early 1890s

-

Wormsloe's oak avenue in summer

-

Replica colonial wattle-and-daub hut

-

Interior of waddle-and-daub hut

-

Portrait of James Oglethorpe

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Tabby". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 2, 2025.

- ^ a b "Johnson v. Wormsloe Foundation". Justia Law. Retrieved August 2, 2025.

- ^ Dan Rice, Susan Knudson, Lisa Westberry, "Restoration of the Wormsloe Plantation Salt Marsh in Savannah Georgia." 2005. Retrieved: September 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Georgia History". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 2, 2025.

- ^ alekmountain (February 17, 2020). "Savannah's Bilbo Mound . . . the oldest architecture and civil engineering in North America". The Americas Revealed. Retrieved August 2, 2025.

- ^ Bauxar, J Joseph (1957). "Yuchi Ethnoarchaeology. Part I: Some Yuchi Identifications Reconsidered". Ethnohistory. 4 (3): 279–301. doi:10.2307/480806. JSTOR 480806.

- ^ E. Merton Coulter, Wormsloe: Two Centuries of a Georgia Family (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1955), 3-5.

- ^ a b "Wormsloe State Historic Site". Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ^ Coulter, 24-5.

- ^ Some information obtained from the Wormsloe Historic Site brochure, published November 2005.

- ^ Coulter, 24.

- ^ Coulter, 56-63.

- ^ "Wormsloe Historic Site | Georgia State Parks". Gastateparks.org. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Slavery in Colonial Georgia". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 3, 2025.

- ^ Spannaus, Nancy (September 14, 2021). "Investigating American Slavery: The Case of Georgia". American System Now. Retrieved August 3, 2025.

- ^ a b c Swanson, Drew A. (2009). "Wormsloe?s Belly: The History of a Southern Plantation through Food". Southern Cultures. 15 (4): 50–66. ISSN 1068-8218.

- ^ Coulter, 22-31.

- ^ Coulter, 121-150.

- ^ a b c Brooks, Robert Preston (1956). "Wormsloe House and Its Masters". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 40 (2): 144–151. ISSN 0016-8297.

- ^ Coulter, 105, 181.

- ^ a b William Harris Bragg, "Wormsloe Plantation." New Georgia Encyclopedia, 24 November 2004. Retrieved: May 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Slave Cabins on Wormsloe Plantation, ca. 1870s" (PDF). De Renne Family Papers, Stereograph, Hargrett Library, University of Georgia.

- ^ Coulter, 238-254.

- ^ Knight, Lucian Lamar (1917). A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians. Lewis publishing Company. p. 71.

- ^ "Craig Barrow Fund - Georgia Historical Society". Georgia Historical Society. Retrieved April 16, 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Gleason, David King (1987). Antebellum Homes of Georgia. Louisiana State University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8071-1432-2.

- Swanson, Drew A. "Wormsloe's Belly." Southern Cultures 15, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 50-66.

- Mayo, Marcia, "The Shadow Playground - Childhood Memories of wormsloe Plantation in the 1950s and 1960s", Georgia Backroads, Autumn 2010, vol 9, #3, pp. 14–16

External links

[edit]- Wormsloe Historic Site — official site at Georgia State Parks

Media related to Wormsloe Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wormsloe Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons- Noble Jones' "Wormslow" 1736-1775 historical marker

- Wormsloe Pamphlet

- William Bartram Trail historical marker at Wormsloe •

- Wormsloe Pamphlet