| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Antisemitism in France is the expression through words or actions of an ideology of hatred of Jews on French soil.

Jews were present in Roman Gaul, but information is limited before the fourth century. As the Roman Empire became Christianized, restrictions on Jews began and many emigrated, some to Gaul. In the Middle Ages, France was a center of Jewish learning, but over time, persecution increased, including multiple expulsions and returns.

During the French Revolution in the late 18th century, on the other hand, France was the first country in Europe to emancipate its Jewish population. Antisemitism still occurred in cycles, reaching a high level in the 1890s, as demonstrated during the most known instance, the Dreyfus Affair, and in the 1940s, under German occupation and the Vichy regime.

During World War II, the Vichy government collaborated with Nazi occupiers to deport a large number of both French Jews and foreign Jewish refugees to concentration camps.[1] Another 110,000 French Jews were living in the colony of French Algeria.[2] By the war's end, 25% of the Jewish population of France had perished in the Holocaust, though this was a lower proportion than in most other countries under Nazi occupation.[3][4] The French Jewish population increased dramatically during the 1950s/60s, as Jews from Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia emigrated to France in large numbers following the independence of those countries.

France today has the third largest Jewish population in the world, behind those of Israel and the United States. However, since 2000, there has been a significant increase in assaults on Jewish people and property, giving rise to a debate about "new antisemitism", with many Jews no longer feeling safe in France. Since 2010 or so, more French Jews have been moving to Israel in response to rising antisemitism in France.[5] In accordance with this, a survey conducted in 2024 found that one in five young French people thinks it would be a good thing that Jews leave the country.[6]

Early period

[edit]Roman Gaul

[edit]The beginning of Jewish presence in Roman Gaul is uncertain. The southern part of France was under the Roman Empire from 122 BCE. Jews spread out after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and more after the Bar Kokhba revolt and the destruction of Jerusalem. Most went towards Rome, where they were offered protection by Julius Caesar, and later by Augustus; and then towards the edges of the Empire. Gaul was an exile destination for banished Roman politicians, and as some Judeans were forced out of their land, likely some of them ended up there as well.[7]

However, it is not until the fourth century that there is reliable documentation of the presence of Jews in Gaul. Not all were from Palestine, some were converted by Jews in the diaspora. As the Roman Empire became Christianized with the recognition of Christianity in 313 and the conversion of Constantine, restrictions on Jews began and increased the pressure on emigration, especially to Gaul which was less Christianized. Numbers were small, and were mostly along the coast, such as Narbonne and Marseille, but also in the river valleys and nearby communities, and extended as far as Clermont-Ferrand and Poitiers.[8]

Jews in Gaul had certain rights, deriving from the Constitutio Antoniniana, decreed in 212 by the Roman Emperor Caracalla to all inhabitants of the Empire, and included freedom of worship, the ability to hold public office, and serve in the army. Jews practiced every trade, and were no different than other Roman citizens, and dressed and spoke the same language as their fellow Romans. Even in the synagogue, where Hebrew was not the only language used. Relations were relatively good.[8]

Information is sketchy, but there is evidence, some dating to the first century, of geographically widespread habitation in Metz, Poitiers, or Avignon. By the fifth century, there is evidence of settlements in Brittany, Orleans, Narbonne, and elsewhere.[9]

Merovingian dynasty

[edit]

After the Fall of Rome, the Merovingians ruled France from the fifth to the eighth century,[9] The emperors Theodosius II and Valentinian III sent a decree to Amatius, prefect of Gaul (9 July 425), that prohibited Jews and pagans from practicing law or holding public offices. This was to prevent Christians from being subject to them and possibly incited to change their faith.[10]

Clovis I converted to Catholicism in 496, along with the majority of the population which brought pressure on Jews to convert as well. The bishops in some localities offered Jews in their purview a choice between baptism and expulsion.[9] In the sixth century, Jews were documented in Marseille, Arles, Uzès, Narbonne, Clermont-Ferrand, Orléans, Paris, and Bordeaux.[10]

The conversion to Christianity of the Visigoths and Franks made the condition of the Jews difficult: a succession of ecumenical councils diminished their rights until Dagobert I forced them to convert or leave France in 633.[11][page needed] During the councils of Elvira (305), Council of Vannes (465), the three Councils of Orleans (533, 538, 541), and the Council of Clermont (535), the Church forbade Jews to have meals together with Christians, to have mixed marriages and proscribed the celebration of the shabbat, the aim being to limit the influence of Judaism on the population.[12]

Middle Ages

[edit]Persecutions under the Capets

[edit]This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (July 2021) |

There were widespread persecutions of Jews in France beginning in 1007.[13] These persecutions, instigated by Robert II (972–1031), King of France (987–1031), called "the Pious", are described in a Hebrew pamphlet,[14][15] which also states that the King of France conspired with his vassals to destroy all the Jews on their lands who would not accept baptism, and many were put to death or killed themselves. Robert is credited with advocating forced conversions of local Jewry, as well as mob violence against Jews who refused.[16] Among the dead was the learned Rabbi Senior. Robert the Pious is well known for his lack of religious toleration and for the hatred that he bore toward heretics; it was Robert who reinstated the Roman imperial custom of burning heretics at the stake.[17] In Normandy under Richard II, Duke of Normandy, Rouen Jewry suffered from persecutions that were so terrible that many women, in order to escape the fury of the mob, jumped into the river and drowned. A notable of the town, Jacob ben Jekuthiel, a Talmudic scholar, sought to intercede with Pope John XVIII to stop the persecution in Lorraine (1007).[18] Jacob undertook the journey to Rome, but was imprisoned with his wife and four sons by Duke Richard, and escaped death only by allegedly miraculous means.[clarification needed] He left his eldest son, Judah, as a hostage with Richard while he with his wife and three remaining sons went to Rome. He bribed the pope with seven gold marks and two hundred pounds, who thereupon sent a special envoy to King Robert ordering him to stop the persecutions.[15][19]

If Adhémar of Chabannes, who wrote in 1030, is to be believed (he had a reputation as a fabricator), the anti-Jewish feelings arose in 1010 after Western Jews addressed a letter to their Eastern coreligionists warning them of a military movement against the Saracens. According to Adémar, Christians urged by Pope Sergius IV[20] were shocked by the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem by the Muslims in 1009. After the destruction, European reaction to the rumor of the letter was of shock and dismay, Cluniac monk Rodulfus Glaber blamed the Jews for the destruction. In that year Alduin, Bishop of Limoges (bishop 990–1012), offered the Jews of his diocese the choice between baptism and exile. For a month theologians held disputations with the Jews, but without much success, for only three or four of Jews abjured their faith; others killed themselves; and the rest either fled or were expelled from Limoges.[21][22] Similar expulsions took place in other French towns.[22] By 1030, Rodulfus Glaber knew more concerning this story.[23] According to his 1030 explanation, Jews of Orléans had sent to the East through a beggar a letter that provoked the order for the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Glaber adds that, on the discovery of the crime, the expulsion of the Jews was everywhere decreed. Some were driven out of the cities, others were put to death, while some killed themselves; only a few remained in the "Roman world". Count Paul Riant (1836–1888) says that this whole story of the relations between the Jews and the Mohammedans is only one of those popular legends with which the chronicles of the time abound.[24]

Another violent commotion arose at about 1065. At this date Pope Alexander II wrote to Béranger, Viscount of Narbonne and to Guifred, bishop of the city, praising them for having prevented the massacre of the Jews in their district, and reminding them that God does not approve of the shedding of blood. In 1065 also, Alexander admonished Landulf VI of Benevento "that the conversion of Jews is not to be obtained by force."[25] Also in the same year, Alexander called for a crusade against the Moors in Spain.[26] These Crusaders killed without mercy all the Jews whom they met on their route.

Crusades

[edit]

The Jews of France suffered during the First Crusade (1096), when the crusaders are stated, for example, to have shut up the Jews of Rouen in a church and to have murdered them without distinction of age or sex, sparing only those who accepted baptism.[27] According to a Hebrew document, the Jews throughout France were at that time in great fear and wrote to their brothers in the Rhine countries making known to them their terror and asking them to fast and pray. In the Rhineland, thousands of Jews were killed by the crusaders (see German Crusade, 1096).[28]

The Rhineland massacres, also known as the German Crusade of 1096,[29] were a series of mass murders of Jews perpetrated by mobs of German Christians of the People's Crusade in the year 1096, or 4856 according to the Jewish calendar. These massacres are seen as the first in a sequence of antisemitic events in Europe which culminated in the Holocaust.[30]

Prominent leaders of crusaders involved in the massacres included Peter the Hermit and especially Count Emicho.[31] As part of this persecution, the destruction of Jewish communities in Speyer, Worms and Mainz was noted as the "Hurban Shum" (Destruction of Shum).[32]

In the County of Toulouse Jews were received on good terms until the Albigensian Crusade. Toleration and favour shown to the Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse. Following the Crusaders' successful wars against Raymond VI and Raymond VII, the Counts were required to discriminate against Jews like other Christian rulers. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII underwent a similar ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris. Explicit provisions on the subject were included in the Treaty of Meaux (1229). By the next generation a new, zealously Catholic, the ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses, seizing their cash, and removing their religious books. They were then released only if they paid a new "tax". A historian has argued that organized and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.[33]

Expulsions and returns

[edit]

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was used during the Middle Ages to enrich the crown, including expulsions:[34]

- from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182[citation needed]

- from Vienne by order of Pope Innocent III in 1253[citation needed]

- from Brittany in 1240[35]

- from Poitou in 1249[35]

- from France by Louis IX in 1254

- by Edward I of England from Gascony in 1288[35]

- from Anjou and Maine in 1289[35]

- from Nevers in 1294[35]

- from Niort in 1296[35]

- from Royal lands by Philip IV in 1306[35]

- by Charles IV in 1322

- by Charles V in 1359

- by Charles VI in 1394.

In 1182, Philip Augustus expelled the Jews from France, and recalled them again in 1198. There were various restrictions on interest on capital or debt in the 13th century under Louis VIII (1223–26) and Louis IX (1226–70). The Medieval Inquisition, which had been instituted in order to suppress Catharism, finally occupied itself with the Jews of Southern France who converted to Christianity. In 1306 the treasury was nearly empty, and the king, as he was about to do the following year in the case of the Templars, condemned the Jews to banishment, and took forcible possession of their property, real and personal. Their houses, lands, and movable goods were sold at auction; and for the king were reserved any treasures found buried in the dwellings that had belonged to the Jews. In 1306, Louis X (1314–16) recalled the Jews. In an edict dated 28 July 1315, he permitted them to return for a period of twelve years, authorizing them to establish themselves in the cities in which they had lived before their banishment.

On 17 September 1394, Charles VI suddenly published an ordinance in which he declared that thenceforth no Jew should dwell in his domains ("Ordonnances", vii. 675). According to the Religieux de St. Denis, the king signed this decree at the insistence of the queen ("Chron. de Charles VI." ii. 119).[36] The decree was not immediately enforced, a respite being granted to the Jews in order that they might sell their property and pay their debts. Those indebted to them were enjoined to redeem their obligations within a set time; otherwise, their pledges held in pawns were to be sold by the Jews. The provost was to escort the Jews to the frontier of the kingdom. Subsequently, the king released the Christians from their debts.[37]

Black Death

[edit]

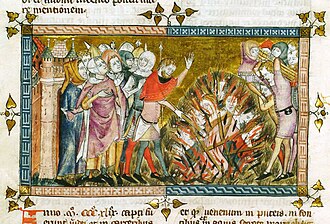

The Black Death plague devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than half of the population, with Jews being made scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, forty Jews were burnt in Toulon as early as April 1348.[38] "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague; they were tortured until they confessed to crimes that they could not possibly have committed.

"The large and significant Jewish communities in such cities as Nuremberg, Frankfurt, and Mainz were wiped out at this time."(1406)[39] In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet's "confession", the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on 14 February 1349.[40][41]

Although Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by the 6 July 1348 papal bull and another 1348 bull, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city.[38] Clement VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews (among whom were the flagellants) had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil."[42]

The first massacre directly related to the plague took place in April 1348 in Toulon, where the Jewish quarter was sacked, and forty Jews were murdered in their homes. Shortly afterward, violence broke out in Barcelona and other Catalan cities.[43] In 1349, massacres and persecutions spread across Europe, including the Erfurt massacre, the Basel massacre, massacres in Aragon, and Flanders.[44][45] 2,000 Jews were burnt alive on 14 February 1349 in the "Valentine's Day" Strasbourg massacre, where the plague had not yet affected the city. While the ashes smouldered, Christian residents of Strasbourg sifted through and collected the valuable possessions of Jews not burnt by the fires.[46][38] Many hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed in this period. Within the 510 Jewish communities destroyed in this period, some members killed themselves to avoid persecution.[47] In the spring of 1349, the Jewish community in Frankfurt am Main was annihilated. This was followed by the destruction of Jewish communities in Mainz and Cologne. The 3,000-strong Jewish population of Mainz initially defended themselves and managed to hold off the Christian attackers. But the Christians managed to overwhelm the Jewish ghetto in the end and killed all of its Jews.[46] At Speyer, Jewish corpses were disposed of in wine casks and cast into the Rhine. By the close of 1349, the worst of the pogroms had ended in Rhineland. But around this time the massacres of Jews started rising near the Hansa townships of the Baltic Coast and in Eastern Europe. By 1351 there had been 350 incidents of anti-Jewish pogroms and 60 major and 150 minor Jewish communities had been exterminated.[citation needed]

Stereotypes and medieval art

[edit]

During the Middle Ages, much art was created by Christians that depicted Jews in a fictional or stereotypical manner; the great majority of narrative religious Medieval art depicted events from the Bible, where the majority of persons shown had been Jewish. But the extent to which this was emphasized in their depictions varied greatly. Some of this art was based on preconceived notions about how Jews dressed or looked, as well as the "sinning" acts that Christians believed that they committed.[48] One iconic symbol of this era was Ecclesia and Synagoga, a pair of statues personifying the Christian Church (Ecclesia) next to her predecessor, the Nation of Israel (synagoga). The latter was often displayed blindfolded and carrying a tablet of the law slipping from her hand, sometimes also bearing a broken staff, whereas Ecclesia was standing upright with a crowned head, a chalice, and a staff adorned with the cross.[49] This was often as a result of a misinterpretation of the Christian doctrine of supersessionism involving a replacement of the "old" covenant given to Moses by the "new" covenant of Christ, which medieval Christians took to mean that the Jews had fallen out of God's favor.[citation needed]

Medieval Christians believed in the idea of Jewish "stubbornness" because Jews did not accept that Christ was the Messiah. This idea extended further in that the Jews dismissed Christ so far that they decided to murder him by nailing him to a cross. Jews were, therefore, marked as the "enemies of Christians" and "Christ-killers."[48] This notion was one of the main inspirations behind antisemitic portrayals of Jews in Christian art.[citation needed]

According to medieval Christians, anyone who did not agree with their ideas of faith, including the Jewish people, was automatically assumed to be friendly with the devil and simultaneously condemned to hell. In many portrayals of Christian art, Jews are made out to resemble demons or interact with the devil. This is meant to not only portray Jews as ugly, evil, and grotesque but also to establish that demons and Jews are innately similar. Jews would also be placed in front of hell to further showcase that they are damned.[48]

By the twelfth century, the concept of a "stereotypical Jew" was widely known. A stereotypical Jew was usually male with a heavy beard, a hat, and a large, crooked nose which were significant identifiers for someone Jewish. These notions were portrayed in medieval art, which ultimately ensured that a Jew could easily be identified. The idea behind a stereotypical Jew was primarily to portray them as ugly creature who is to be avoided and feared.[48]

Ancien Regime

[edit]

The Ancien Regime was the political and social system of the Kingdom of France from the Late Middle Ages (circa 15th century) until the French Revolution of 1789, during the period known as Early Modern France and epitomized by the 72-year reign (1643–1715) of King Louis XIV. In the run-up to the Revolution, France had a Jewish population of around 40,000 to 50,000, chiefly centered in Bordeaux, Metz and a few other cities. They had very limited rights and opportunities, apart from the moneylending business, but their status was legal.[50]

Jewish residents of France lived on the periphery of the country: in the southwest, southeast, and northeast under conditions inherited from the Middle Ages, with only around 400 in Paris. Their main concern was simply to maintain their right of residency, which involved significant financial payments to various rulers, which was complex due to the division of authority between king and local seigneurs. In return, Jews were allowed to live in specific places, and occupy certain limited occupations, especially moneylending, and secondhand sales. Jews were a tolerated alien group that formed their own self-governing community, parallel to the general social order, but not quite part of it, and governed by their own halakha law. Although suffering social antipathy, they were able to practice their religion; in some areas only fairly recently. Of the various Jewish communities, the Marranos of the southwest, principally from Bordeaux, were the most commercially valued by the Crown, and were the most socially acculturated to general French society. Expelled from France in the 14th century, their privileges were once again recognized by Louis XV in 1723, primarily due to their economic utility as bankers and brokers.[51]

Revolutionary France

[edit]Run-up to Revolution

[edit]

Before the French Revolution, the hostility of Voltaire made him place in his Philosophical Dictionary an exhortation addressed to the Jews: "you are calculating animals; try to be thinking animals".[52] In the 1770s, the majority of contributors to the Encyclopédie and other thought leaders (excepting rare philosemites like Irish philosopher John Toland in 1714, or Protestant pastor Jacques Basnage de Beauval in 1716[53]), who were busy defending the civil rights of the black inhabitants of the Antilles, the Hurons of North America, or other tribes, forgot to plead for the emancipation of their immediate neighbors, the Jews of France, and instead covered them with accusations and mockery.[53] Nevertheless, Diderot, in one of the longest articles of The Encyclopedia, the article Juif ("Jew"), does "justice to the importance of the destiny of the Jewish people, and the richness of their ideas".[54]

Severe measures were taken against the Jews of Alsace (about 20,000 people) through the letters patent of 10 July 1784: limitation of the number of Jews and their marriages, economic restrictions, and other measures.[55] On the other hand, the edict of January 1784 by Louis XVI exempted the other Jews "from the duties of Leibzoll, traverse, custom[clarify] and all other duties of this nature for their person only" which previously equated them with animals.[56] In 1787, the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences of Metz launched a contest: "Are there ways to make the Jews happier and more useful in France?"[a]

French Revolution

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. Find sources: "French Revolution" Jews – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) |

Jews gained equal rights to French citizenship when the National Assembly voted it in on 27 September 1791. An amendment was added later, removing certain privileges granting some autonomous rule to Jewish communities; these were removed, in order that Jews as individuals have the same rights as any other French citizen, neither more nor less.[57]

Napoleon and First Empire

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. Find sources: "Jews" Napoleon OR "First Empire" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) |

In the early 19th century, through his conquests in Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte spread the modernist ideas of revolutionary France: equality of citizens and the rule of law. Napoleon's personal attitude towards the Jews has been interpreted in various ways by different historians, as at various times he made statements both in support of and in opposition to the Jewish people. Orthodox Rabbi Berel Wein claimed that Napoleon was interested primarily in seeing the Jews assimilate, rather than prosper as a distinct community: "Napoleon's outward tolerance and fairness toward Jews was actually based upon his grand plan to have them disappear entirely by means of total assimilation, intermarriage, and conversion."[58]

In one 1822 communication, Napoleon expressed his support of emancipation based on his wish to "leave off usury" and "make them become good citizens",[59] whereas in 1808, he had expressed a conflicting view to his brother Jérome Napoleon, saying, "I have undertaken to reform the Jews, but I have not endeavoured to draw more of them into my realm. Far from that, I have avoided doing anything which could show any esteem for the most despicable of mankind."[60]

Third Republic

[edit]Media and organizations

[edit]Three antisemitic publications were formed in the 1882–1885 period, but did not last long: L'Anti-Juif, L'Anti-Sémitique, and Le Péril sociale.[61]

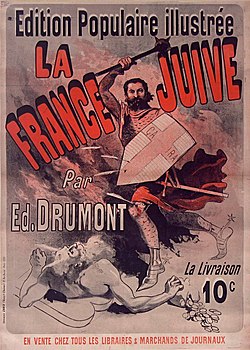

Edouard Drumont published his 1200-page antisemitic tract La France juive ("Jewish France") in 1886.[61] A best-seller of its time, it was immensely popular[62][page needed] and went through 140 printings in the first two years after initial publication. The book was so popular, it spawned its own literary genre, which saw the production in 1887 of Jewish Russia by Calixte de Wolski and Jewish Algeria by Georges Meynié, Jewish Austria by François Trocase in 1900, and Jewish England by Doedalus in 1913.[62][page needed] Drumont's book was reprinted in 1938, 1986, and 2012; and in digital version in 2018.

Inspired by the success of the book, Drumont and Jacques de Biez [fr] founded the Antisemitic League of France (Ligue antisémitique de France) in 1889. It was active in the Dreyfus Affair.[61] Jules Guérin was an active member. The League organized demonstrations and riots, a tactic later copied by other far-right organizations.[citation needed] Guerin edited the anti-Dreyfusard weekly newspaper L'Antijuif as the official organ of the Antisemitic League from 1898 to 1899.[63]

The International Review of Secret Societies [fr], directed at first by Ernest Jouin and later by Canon Schaefer, leader of the Free-Catholic League [fr], went from 200 subscribers in 1912 to 2000 in 1932.[64] The Catholic journalist Léon de Poncins, a follower of conspiracy theories and a contributor to many newspapers (including Le Figaro, directed by François Coty, or L'Ami du Peuple, subtitled "Weekly magazine of racialist action against occult forces"[b] participated in it,[64] as did the occultist Pierre Virion, who founded an association after the war with General Weygand,[65] the Vichy Minister of National Defense, before enforcing racist laws in North Africa.[64]

Le Grand Occident, run by the anti-Dreyfusards Lucien Pemjean [fr], Jean Drault [fr] and Albert Monniot [fr], printed 6,000 copies in 1934. Le Réveil du peuple, organ of the Front Franc ('The French Front') of Jean Boissel, to which Jean Drault [fr] and Urbain Gohier collaborated, distributed 3,000 copies in 1939.[64] Having ceased publication in 1924, La Libre Parole started up again in 1928–1929, without commercial success, then in 1930 by Henry Coston (alias Georges Virebeau), who directed it until the war. Many famous antisemites wrote for the paper, including Jacques Ploncard, Jean Drault [fr], Henri-Robert Petit, Albert Monniot [fr], Mathieu Degeilh, Louis Tournayre and Jacques Ditte. The monthly magazine of the same had a circulation of 2000 subscribers.[64]

Other reviews were more fleeting, such as La France Réelle, close to L'Action francaise; the pro-fascist L'Insurgé, or L'Ordre National, close to La Cagoule, an anti-communist and antisemitic terrorist group financed by Eugène Schueller, founder of L'Oréal. The latter published articles by Hubert Bourgin and Jacques Dumas.[64]

Panama Canal Scandal

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The Panama Canal Scandal was a corruption affair that broke out in the French Third Republic in 1892, linked to a French company's failed attempt at building a canal through Panama. Close to half a billion francs were lost. Members of the French government took bribes to keep quiet about the Panama Canal Company's financial troubles in what is regarded as the largest monetary corruption scandal of the 19th century.[66]

Hannah Arendt argues that the affair had an immense importance in the development of French antisemitism, due to the involvement of two Jews of German origin, Baron Jacques de Reinach and Cornelius Herz.[67] Although they were not among the bribed Parliament members or on the company's board, according to Arendt they were in charge of distributing the bribe money, Reinach among the right wing of the bourgeois parties, Herz among the anti-clerical radicals. Reinach was a secret financial advisor to the government and handled its relations with the Panama Company.[67] Herz was Reinach's contact in the radical wing, but Herz's double-dealing blackmail ultimately drove Reinach to suicide.

However, before his death Reinach gave a list of the suborned members of Parliament to La Libre Parole, Edouard Drumont's antisemitic daily, in exchange for the paper's covering up Reinach's own role. Overnight, the story transformed La Libre Parole from an obscure sheet into one of the most influential papers in the country. The list of culprits was published morning by morning in small installments, so that hundreds of politicians had to live on tenterhooks for months. In Arendt's view, the scandal showed that the middlemen between the business sector and the state were almost exclusively Jews, thus helping to pave the way for the Dreyfus Affair.[68]

Dreyfus Affair

[edit]

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided the Third French Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolize modern injustice in the Francophone world,[69] and it remains one of the most notable examples of a complex miscarriage of justice and antisemitism. The role played by the press and public opinion proved influential in the conflict.

The scandal began in December 1894 when Captain Alfred Dreyfus of Alsatian Jewish descent was convicted of treason. He was sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly communicating French military secrets to the Germans, and was imprisoned in Devil's Island in French Guiana, where he spent nearly five years.

Antisemitism was a prominent factor throughout the affair. Existing prior to the Dreyfus affair, it had expressed itself during the boulangisme affair and the Panama Canal scandal but was limited to an intellectual elite. The Dreyfus Affair spread hatred of Jews through all strata of society, a movement that certainly began with the success of Jewish France by Édouard Drumont in 1886.[70] It was then greatly amplified by various legal episodes and press campaigns for nearly fifteen years. Antisemitism was thenceforth official and was evident in numerous settings including the working classes.[71] Candidates for the legislative elections took advantage of antisemitism as a watchword in parliamentary elections. This antisemitism was reinforced by the crisis of the separation of church and state in 1905, which probably led to its height in France. Antisemitic actions were permitted on the advent of the Vichy regime, which allowed free and unrestrained expression of racial hatred.[citation needed]

Antisemitic riots

[edit]Antisemitic riots predated the Dreyfus Affair, and were almost a tradition in the East, where "the Alsatian people observed upon the outbreak of any revolution in France".[72] But the antisemitic riots that broke out in 1898 during the Dreyfus Affair were much more widespread. There were three waves of violence during January and February in 55 localities: the first ending the week of 23 January; the second wave in the week following; and the third wave from 23–28 February;[73] these waves and other incidents totaled 69 riots or disturbances across the country.[74] Additionally, riots took place in French Algeria from 18–25 January. Demonstrators at these disturbances threw stones, chanted slogans, attacked Jewish property and sometimes Jewish people, and resisted police efforts to stop them. Mayors called for calm, and troops including cavalry were called in an attempt to quell the disturbances.[73]

Emile Zola's famous account J'Accuse appeared in L'Aurore on 13 January 1898, and most histories suggest that the riots were spontaneous reactions to its publication, and the subsequent Zola trial, with reports that "tumultuous demonstrations broke out nearly every day". Prefects or police in various towns noted demonstrations in their localities, and associated them with "the campaign undertaken in favor of ex-Captain Dreyfus", or with the "intervention by M. Zola", or the Zola trial itself, which "seems to have aroused the antisemitic demonstrations". In Paris, demonstrations around the Zola trial were frequent and sometimes violent. Martin du Gard reported that "Individuals with Jewish features were grabbed, surrounded, and roughed up by delirious youths who danced round them, brandishing flaming torches, made from rolled-up copies of L'Aurore.[73]

However the fervid reaction to the Affair and especially the Zola trial was only partly spontaneous. In a dozen cities including Nantes, Lille, and Le Havre, antisemitic posters appeared in the streets, and riots followed soon after. At Saint-Etienne, posters read, "Imitate your brothers of Paris, Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, Toulouse... join with them in demonstrating against the underhand attacks being made on the Nation." In Caen, Marseille, and other cities, riots followed antisemitic speeches or meetings, such as the meeting organized by the Comité de Défense Religieuse et Sociale in Caen.[73]

Popular Front

[edit]Vichy regime

[edit]During World War II, the Vichy government collaborated with Nazi Germany to arrest and deport a large number of both French Jews and foreign Jewish refugees to concentration camps.[1] By the war's end, 25% of the Jewish population of France had perished in the Holocaust.[3][4]

Aryanization

[edit]Aryanization was the forced expulsion of Jews from business life in Nazi Germany, Axis-aligned states, and their occupied territories. It entailed the transfer of Jewish property into "Aryan" hands. The process started in 1933 in Nazi Germany with transfers of Jewish property and ended with the Holocaust.[75][76] Two phases have generally been identified: a first phase in which the theft from Jewish victims was concealed under a veneer of legality, and a second phase, in which property was more openly confiscated. In both cases, Aryanization corresponded to Nazi policy and was defined, supported, and enforced by Germany's legal and financial bureaucracy.[77][78] Between $230 and $320 billion (in 2005 [US] dollars) was stolen from Jews across Europe,[79] with hundreds of thousands of businesses Aryanized.

The term is also used by historians to refer to the spoliation of French Jews, carried out jointly and concurrently by the German occupier and the Vichy regime. It followed the law of 22 July 1941 of the "French State", which itself followed the relentless Aryanization by the Germans in the fall of 1940 in the occupied zone. Long neglected, the spoliation of Jewish property has become a highly developed field of research since the 1990s.

The dispossession of Jews was from the outset included in the mission statement of the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, created on 29 March 1941 and directed first by Xavier Vallat and then by Louis Darquier de Pellepoix. From the summer of 1940, various German departments were also actively engaged in stealing Jewish property. Ambassador Otto Abetz took advantage of the 1940 mass exodus to southern France to steal the art collections of absent Jewish owners. At the end of 1941, the Germans imposed an exorbitant fine of one billion francs on the French Jewish community, to be paid among other things upon the sale of Jewish property, and managed by the Caisse des dépôts et consignations.

Historian Henry Rousso estimated the number of Aryanized companies at 10,000.[80] There were 50,000 appointments administrators of Jewish property during the Occupation. By 1940, 50% of the Jewish community was deprived of their normal livelihood according to Vichy laws prohibiting them from many occupations as well as by German ordinances.[81]

Propaganda

[edit]Le Juif et la France (The Jews and France) was an antisemitic propaganda exhibition that took place in Paris from 5 September 1941 to 15 January 1942[82] during the German occupation of France. A film version of the exhibition came out in French cinemas in October 1941.[83]

It was organized and financed by the propaganda arm of the German military administration in France via the Institut d'étude des questions juives (IEQJ) (Institute for the Study of Jewish Questions) under regulation by the Gestapo and attracted around half a million visitors.[82][83] This exhibition was based on the work of Professor George Montandon at the School of Anthropology in Paris, author of the book Comment reconnaître le Juif? (How to recognize a Jew?) published in November 1940. It had pretensions of being "scientific". It was opened by Carltheo Zeitschel and Theodor Dannecker on 5 September 1941[84][page needed][85] at the Palais Berlitz.[86]

Anti-Jewish legislation

[edit]

Anti-Jewish laws were enacted by the Vichy government in 1940 and 1941 affecting metropolitan France and its overseas territories during World War II. These laws were, in fact, decrees by the head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain, since Parliament was no longer in office as of 11 July 1940. The motivation for the legislation was spontaneous and was not mandated by Germany.[87][88]

In July 1940, Vichy set up a special commission charged with reviewing naturalizations granted since 1927 reform of the nationality law.[89] Between June 1940 and August 1944, 15,000 persons, mostly Jews, were denaturalized.[90] This bureaucratic decision was instrumental in their subsequent internment in the green ticket roundup.[citation needed]

Pétain personally made the 3 October 1940 law even more aggressively antisemitic than it initially was, as can be seen by annotations made on the draft in his own hand.[91] The law "embraced the definition of a Jew established in the Nuremberg Laws",[92] deprived the Jews of their civil rights, and fired them from many jobs. The law also forbade Jews from working in certain professions (teachers, journalists, lawyers, etc.) while the law of 4 October 1940 provided authority for the incarceration of foreign Jews in internment camps in southern France such as Gurs.

The statutes were aimed at depriving Jews of the right to hold public office, designating them as a lower class, and depriving them of citizenship.[93][94][95] Many Jews were subsequently rounded up at Drancy internment camp before being deported for extermination in Nazi concentration camps.

After the liberation of Paris when the Provisional government was in control under Charles de Gaulle, these laws were declared null and void on 9 August 1944.[96]

The Holocaust

[edit]

Between 1940 and 1944 Jews in occupied France, the zone libre, and in Vichy-controlled French North Africa as well as Romani people were persecuted, rounded up in raids, and deported to Nazi death camps. The persecution began in 1940, and culminated in deportations of Jews from France to Nazi concentration camps in Nazi Germany and Nazi-occupied Poland. The deportations started in 1942 and lasted until July 1944. Of the 340,000 Jews living in metropolitan/continental France in 1940, more than 75,000 were deported to death camps, where about 72,500 were murdered. The government of Vichy France and the French police organized and implemented the roundups of Jews.[97]

Roundups

[edit]French police carried out numerous roundups of Jews during World War II, including the Green ticket roundup in 1941,[98][99] the massive Vélodrome d'Hiver round-up in 1942 in which over 13,000 Jews were arrested,[100][101] and the roundup in the Old Port of Marseille in 1943.[102] Almost all of those arrested were deported to Auschwitz or other death camps.

Green ticket roundup

[edit]

The green ticket roundup took place on 14 May 1941 during the Nazi occupation of France. The mass arrest started a day after French Police delivered a green card (French: billet vert) to 6694 foreign Jews living in Paris, instructing them to report for a "status check".[103]

Over half reported as instructed, most of them Polish and Czech. They were arrested and deported to one of two transit camps in France. Most of them were interned for a year before getting deported to Auschwitz and murdered. The Green ticket roundup was the first mass round-up of Jewish people by the Vichy Regime.[99]

July 1942 Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

[edit]

In July 1942 the French police organized the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup (Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv) under orders of René Bousquet and his second in Paris, Jean Leguay, with co-operation from authorities of the SNCF, the state railway company. The police arrested 13,152 Jews, including 4,051 children – which the Gestapo had not asked for – and 5,082 women, on 16 and 17 July and imprisoned them in the Vélodrome d'Hiver. They were led to Drancy internment camp and subsequently crammed into box cars and shipped by rail to Auschwitz extermination camp. Most of the victims died en route due to a lack of food or water. Those who survived were murdered in the gas chambers. This action alone represented more than a quarter of the 42,000 French Jews sent to concentration camps in 1942, of whom only 811 would survive the war. Although the Nazis had directed the action, French police authorities vigorously participated without resisting.[104]

1941 Paris synagogue attacks

[edit]On the night of 2–3 October 1941, six synagogues in Paris were attacked and damaged by explosive devices placed by their doors.[105]

Helmut Knochen, Chief Commandant of the Sicherheitspolizei (Nazi Occupying Security Services)[106] ordered the attacks on the Paris synagogues.[citation needed] Members of the Milice placed the bombs.[citation needed] The Revolutionary Social Movement (MSR), a Far-right political party was also implicated in the attacks.[107]

According to the Vichy correspondent of the Swiss newspaper Feuille d'Avis de Neuchâtel et du Vignoble neuchâtelois, on Saturday, 4 October 1941:

On the night of Thursday and Friday in Paris between 1 am and 5 am, attacks took place against seven synagogues. The Synagogue de la rue de Tournelle [sic], Synagogue de la rue Montespan [sic], Synagogue de la rue Copernic, Synagogue de Notre-Dame de Lazaret [sic], Synagogue de Notre-Dame des victoires and a sixth located on a road in which we don't yet know the name were attacked. The damage is considerable, as just the walls remain. The bomb at the Synagogue de la rue Pavée, near City Hall, was removed in time. Two people were injured. Admiral Dard, Prefect of Police, arrived on the scene and is leading the investigation. The attacks took places the day after the Day of Atonement.[108]

The perpetrators were identified but not arrested.[citation needed]

Organized plunder

[edit]Nazi Germany plundered cultural property in Germany and from all the territories they occupied, targeting Jewish property in particular. Several organizations were created expressly for the purpose of looting books, paintings, and other cultural artefacts.[109]

Post-World War II

[edit]In 1949, a spate of antisemitic attacks targeted Jewish shops and cafes in Paris. Following initial attacks, suspects used camouflaged crates of goods containing explosives.[110]

Algeria

[edit]Background

[edit]

There is evidence of Jewish settlements in Algeria since at least the Roman period (Mauretania Caesariensis).[111] In the 7th century, Jewish settlements in North Africa were reinforced by Jewish immigrants that came to North Africa after fleeing from the persecutions of the Visigothic king Sisebut[112] and his successors. They escaped to the Maghreb and settled in the Byzantine Empire. Later many Sephardic Jews were forced to take refuge in Algeria from the persecutions in Spain in 1391 and the Spanish Inquisition in 1492.[113] They thronged to the ports of North Africa, and mingled with native Jewish people. In the 16th century there were large Jewish communities in places such as Oran, Bejaïa and Algiers. By 1830, the Algerian Jewish population numbered 15,000, mostly congregated in the coastal area, with about 6,500 \in Algiers, where they made up a fifth of the population.[114]

The French government granted Jews, who by then numbered some 33,000,[115] French citizenship in 1870 under the Crémieux Decree[116] The decision to extend citizenship to Algerian Jews was a result of pressures from prominent members of the liberal, intellectual French Jewish community, which considered the North African Jews to be "backward" and wanted to bring them into modernity.[citation needed]

Within a generation, despite initial resistance, most Algerian Jews came to speak French rather than Arabic or Ladino, and they embraced many aspects of French culture. In embracing "Frenchness," the Algerian Jews joined the colonizers, although they were still considered "other" to the French. Although some took on more typically European occupations, "the majority of Jews were poor artisans and shopkeepers catering to a Muslim clientele."[117] Moreover, conflicts between Sephardic Jewish religious law and French law produced contention within the community. They resisted changes related to domestic issues, such as marriage.[118]

French antisemitism set down strong roots among the expatriate French community in Algeria, where every municipal council was controlled by antisemites, and newspapers were rife with xenophobic attacks on the local Jewish communities.[119] In Algiers when Émile Zola was brought to trial for his defense in an 1898 open letter, J'Accuse...!, of Alfred Dreyfus, over 158 Jewish-owned shops were looted and burned and two Jews were killed, while the army stood by and refused to intervene.[120]

A Vichy law of 7 October 1940 (pub. 8 October in the JO) abrogated the Cremieux decree and denaturalized the Jewish population of Algeria.[121]

Struggle for independence

[edit]The Jewish community in Algeria had always been in a fragile position. After World War II, the Algerian Jewish community formed a number of organizations to support and safeguard religious institutions. The fate of the community was determined by the Algerian nationalist struggle for independence. Already in 1956, the Algerian National Liberation Front had appealed to "Algerians of Jewish origin" to choose Algerian nationality. Fears increased in 1958 when the FLN kidnapped and killed two officials of the Jewish Agency, and in 1960 with desecrations of the Great Synagogue of Algiers and the Jewish cemetery in Oran, and others were killed by the FLN.[122]

Most Algerian Jews in 1961 still hoped for a solution of partition or dual nationality that would permit a resolution of the conflict, and groups such as the Comité Juif Algérien d'Etudes Sociales attempted to straddle the question of identity. Fears increased with the increasing terrorist activity by the OAS (Organisation armée secrète) and FLN, and emigration rose rapidly in mid-1962 with 70,000 leaving for France and 5,000 opting for Israel. The French government treated Jews and non-Jewish immigrants equally, and 32,000 Jews settled in the Paris area, with many others heading to Strasbourg which already had an established community. Estimates are that 80% of Algeria's Jewish community settled in France.[122]

For those Jews still present after Algerian independence in 1962, the situation remained tolerable for a few years, with the minister of culture addressing the congregation on Yom Kippur. But the situation worsened rapidly with the accession to power of Houari Boumédienne in 1965, with the imposition of heavy taxes and a rise in discrimation, including lack of protection from the courts, and attacks from the press in 1967, cemeteries decayed, synagogues were defaced. By 1969 there were fewer than one thousand Jews left, aging or unwilling to leave their homes. By the 1990s, one synagogue was left; the rest had been converted to mosques, and around fifty Jews remained.[122]

Assaults and desecrations

[edit]1980 Paris synagogue bombing

[edit]

On 3 October 1980, the rue Copernic synagogue in Paris, France, was bombed in a terrorist attack. The attack killed four and wounded 46 people. The bombing took place in the evening near the beginning of Shabbat, during the Jewish holiday of Sim'hat Torah. It was the first deadly attack against Jewish people in France since the end of the Second World War.[123] The Federation of National and European Action (FANE) claimed responsibility,[124] but the police investigation later concluded that Palestinian nationalists were likely responsible.[125][126]

1982 Paris restaurant bombing

[edit]On 9 August 1982 the Abu Nidal Organization carried out a bombing and shooting attack on a Jewish restaurant in Paris's Marais district. Two assailants threw a grenade into the dining room, then rushed in and fired machine guns.[127] They killed six people, including two Americans[128] and injured 22 others. Business Week later said it was "the heaviest toll suffered by Jews in France since World War II."[129][130] The restaurant closed in 2006 and former owner Jo Goldenberg died in 2014.[131]

Although the Abu Nidal Organization had long been suspected,[132][133] suspects from the group were only definitively identified 32 years after the attacks, in evidence given by two former Abu Nidal members granted anonymity by French judges.[134]

In December 2020 one of the suspects, Walid Abdulrahman Abou Zayed, was handed over to French police (at a Norwegian airport) and flown to France.[135][136][137] Later in December, he was being held at La Sante Prison in Paris.[138] As of March 2021, he is still in prison.[139]

Carpentras cemetery 1990

[edit]On 10 May 1990, a Jewish cemetery at Carpentras was desecrated. This led to a public uproar, and a protest demonstration in Paris attended by 200,000 persons, including French President François Mitterrand. After several years of investigation, five people, among them three former members of the extremist far-right French and European Nationalist Party confessed on 2 August 1996.[140][141] On 5 June 1990, the PNFE magazine Tribune nationaliste was banned by the French authorities.[142]

Since 2000

[edit]France has the largest population of Jews in the diaspora after the United States – an estimated 500,000–600,000 people. Paris has the highest population, followed by Marseille, which has 70,000 Jews, most of North African origin. Expressions of antisemitism were seen to rise during the Six-Day War of 1967 and the French anti-Zionist campaign of the 1970s and 1980s.[143][144] Following the electoral successes achieved by the extreme right-wing National Front and an increasing denial of the Holocaust among some persons in the 1990s, surveys showed an increase in stereotypical antisemitic beliefs among the general French population.[145][146][147] Since 2023, France has experienced a sharp increase in reported antisemitic incidents compared to previous years.[148][149][150] A 2024 survey showed that 68% of French Jews feel unsafe in light of rising antisemitism.[151]

Speech and writing

[edit]Dieudonné

[edit]Public personalities have caused controversy by their positions which they call "anti-Zionist". This is the case of comedian Dieudonné,[152][153] who was convicted of incitement to racial hatred,[154] and who, during the European elections of 2009, led an "Anti-Zionist slate"[155] along with essayist Alain Soral, president of Égalité et Réconciliation, and Yahia Gouasmi, creator of the Anti-Zionist Party.[156][157][158] Despite gaining notoriety in his duo with Jewish comedian, Elie Semoun, in 1997 Dieudonné began incorporating antisemitism in his comedy and in his public persona. He was a proponent of the myth of Jewish conspiracy and power, often tying his anti-zionism with claims about "the Jewish lobby" and "the Jewish media." He touted Jewish responsibility for slavery and Jewish racism against Blacks and Arabs as reason for his beliefs about Jewish control, and allied with Holocaust deniers. Dieudonné leveled antisemitic attacks against many prominent French Jews such as Dominique Strauss-Kahn and Bernard-Henri Lévy among others. His antisemitism fuels his political and social campaigns, which resulted in a wave of antisemitic attacks against French Jews, including the killing of Ilan Halimi.[159] Dieudonné has been fined ten of thousands of euros for defamation regarding antisemitic statements.[160]

Cercle Édouard Drumont

[edit]The "Cercle Édouard Drumont" (named after the author of the antisemitic essay La France juive) was formed in 2019 to "honor" this "great man" and "nationalist" activist. For Libération journalist Pierre Plottu, this circle is close to Amitié et Action française, a dissident faction of Action française[161] directed by lawyer Elie Hatem [fr] who also organizes meetings where "the guest list is a who's who of the French antisemitic far right: Yvan Benedetti but also Jérôme Bourbon [fr] (from the denialist newspaper Rivarol, Alain Escada (head of the national catholics of Civitas), the Soralian Marion Sigaut [fr], Pierre-Antoine Plaquevent (obsessed with Soros and 'the immigrant invasion'), Stéphanie Bignon (from Terre et Famille, close to Civitas), or the prince Sixte-Henri de Bourbon-Parme who is close to personalities of the rightist Rassemblement national."[162]

Attacks

[edit]Passover 2002 attacks

[edit]A series of attacks on Jewish targets in France took place in a single week in 2002, coinciding with the Jewish holiday of Passover, including at least five synagogues.[163][164] The targeted synagogues include the Lyon synagogue, the Or Aviv synagogue in Marseille, which burned to the ground; a synagogue in Strasbourg, where a fire was set that burned the doors and facade of the building before being doused;[165] and the firebombing of a synagogue in the Paris suburb of Le Kremlin-Bicêtre.[164]

Lyon synagogue

[edit]On 30 March 2002, a group of masked men rammed two cars through the courtyard gates of a synagogue in the La Duchere [fr] neighborhood of Lyon, France, then rammed one of the cars into the prayer hall before setting the vehicles on fire and causing severe damage to the synagogue.

The attack took place at 1:00 am on a Saturday morning; the building was empty at the time. The attackers wore masks or hoods covering their faces, and eyewitnesses reported seeing twelve or fifteen attackers.[166][167][163][168]

2006 murder of Ilan Halimi

[edit]

Ilan Halimi was a young Frenchman of Moroccan Jewish ancestry living in Paris with his mother and his two sisters.[169] On 21 January 2006, Halimi was kidnapped by a group calling itself the Gang of Barbarians. The kidnappers, believing that all Jews are rich, repeatedly contacted the victim's family of modest means demanding very large sums of money.[170]

After three weeks and no success in finding the captors, the family and the police stopped receiving messages from the captors. Halimi, severely tortured, burned over more than 80% of his body, was dumped unclothed and barely alive by the side of a road in Sainte-Geneviève-Des-Bois on 13 February 2006. He was found by a passerby who immediately called for an ambulance, but Halimi died from his injuries on the way to the hospital.[citation needed]

The French police were heavily criticized because they initially believed that antisemitism was not a factor in the crime.[171] The case drew national and international attention as an example of antisemitism in France.[170]

2012 Jewish day school shooting

[edit]The Ozar Hatorah school in Toulouse is part of a national chain of at least twenty Jewish schools throughout France. It educates children of primarily Sephardic, Middle Eastern and North African descent, who with their parents have made up the majority of Jewish immigrants to France since the late 20th century. The school is a middle and secondary school, with most children between the ages of 11 and 17.

At about 8:00 am on 19 March 2012, a man rode up to the Ozar Hatorah school on a motorcycle. Dismounting, he immediately opened fire toward the schoolyard. The first victim was 30-year-old Jonathan Sandler, a rabbi and teacher at the school who was shot outside the school gates as he tried to shield his two young sons from the gunman. The gunman shot both the boys – 5-year-old Arié and 3-year-old Gabriel[172] – before walking into the schoolyard, chasing people into the building.

Inside, he shot at staff, parents, and students. He chased 8-year-old Myriam Monsonego,[173] the daughter of the head teacher, into the courtyard, caught her by her hair and raised a gun to shoot her. The gun jammed at this point. He changed weapons from what the police identified as a 9mm pistol to a .45 calibre gun, and shot the girl in her temple at point-blank range.[129][174][175][176] Bryan Bijaoui, a 17-year-old[177] boy, was also shot and gravely injured.[178] The gunman retrieved his scooter and rode away.

The government was already providing continuous protection to many Jewish institutions, but it increased security and raised the terrorist warnings to the highest level. Traffic on streets in France with Jewish institutions was closed for additional security.[129] The election campaign was suspended and President Nicolas Sarkozy, as well as other candidates in the presidential elections, immediately traveled to Toulouse and the school.[179]

Supermarket siege

[edit]

On 9 January 2015, Amedy Coulibaly, who had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant,[180] attacked the people in a Hypercacher kosher food supermarket at Porte de Vincennes in east Paris. He killed four people, all of whom were Jewish,[181][182] and took several hostages.[183][184] Some media outlets claimed he had a female accomplice, speculated initially to be his common-law wife, Hayat Boumeddiene.[185]

2017 Killing of Sarah Halimi

[edit]Sarah Halimi (no relation to Ilhan Halimi) was a retired doctor and schoolteacher who was attacked and killed in her apartment on 4 April 2017. The circumstances surrounding the killing – including the fact that Halimi was the only Jewish resident in her building, and that the assailant shouted Allahu akbar during the attack and afterward proclaimed "I killed the Shaitan" – cemented the public perception of the incident, particularly among the French Jewish community, as a stark example of antisemitism in modern France.

For several months the government and some of the media hesitated to label the killing as antisemitic, drawing criticism from public figures such as Bernard-Henri Lévy. The government eventually acknowledged an antisemitic motivation for the killing. The assailant was declared to be not criminally responsible when the judges ruled he was undergoing a psychotic episode due to cannabis consumption, as established by independent psychiatric analysis.[186] The decision was appealed to the supreme Court of Cassation,[187] who in 2021 upheld the lower court's ruling.[188]

The killing has been compared to the murder of Mireille Knoll in the same arrondissement less than a year later, and to the murder of Ilan Halimi (no relation) eleven years earlier.[189]

Murder of Mireille Knoll

[edit]

Mireille Knoll was an 85-year-old French Jewish woman holocaust survivor who was murdered in her Paris apartment on 23 March 2018. The murder has been officially described by French authorities as an antisemitic hate crime.

Of the two alleged assailants, one was a 29-year-old neighbor of Knoll, who suffered from Parkinson's disease,[190] and had known her since he was a child, and the other, an unemployed 21-year-old. The two suspects entered the apartment and reportedly stabbed Knoll eleven times before setting her on fire.[191][192][193]

The Paris prosecutor's office characterized the 23 March murder as a hate crime, a murder committed because of the "membership, real or supposed, of the victim of a particular religion." The New York Times noted, "The speed with which the authorities recognized the hate-crime nature of Ms. Knoll's murder is being seen as a reaction to the anger of France's Jews at the official response to that earlier crime, which prosecutors took months to characterize as antisemitic."[194][195][196]

During the 2023 war

[edit]According to a report from the Conseil Représentatif des Institutions juives de France (CRIF), the number of antisemitic crimes in France in 2023 nearly quadrupled compared to 2022, with 1,676 reported incidents.[148] In 2024, the number remained high, reaching 1,570 antisemitic incidents.[149]

In response to a rise in antisemitic incidents in France during the Gaza war, the French government banned pro-Palestinian demonstrations in the country. In a televised address on 12 October 2023, French President Emmanuel Macron warned, "Let's remember that antisemitism has always been the precursor to other forms of hate: one day against the Jews, the next against the Christians, then the Muslims, and then all those who are still the target of hate due to their culture, origin or gender."[197]

On 31 October 2023, Stars of David were painted in multiple spots across several building fronts in a southern district of Paris. Similar tags appeared over the weekend in suburbs of the city, including Vanves, Fontenay-aux-Roses and Aubervilliers.[198]

On 4 November 2023, a Jewish woman was stabbed in Lyon and a swastika was graffitied on her home.[199]On 17 May 2024, a synagogue in Rouen was set on fire by an Algerian man, who threw a petrol bomb through a small window. The fire inside the synagogue was eventually brought under control by firefighters, with no reported victims other than the arsonist, who was shot by the police. The synagogue was significantly damaged, although the Torah scrolls remained unharmed.[200][201] Since the beginning of the war, there have been approximately 100 antisemitic incidents per month, threatening to become a new norm.[202]

On 17 June 2024, a 12-year-old Jewish girl in Paris was gang-raped by three boys aged 12 to 14 in an abandoned hangar. The attack, which included antisemitic slurs, occurred after the girl's former boyfriend accused her of hiding her Jewish identity. The suspects were arrested, and investigators found antisemitic content on one of their phones.[203][204][205] Another suspect admitted to hitting the victim due to her negative comments about Palestine.[206] The girl was reportedly called a "dirty Jew" and received death threats.[207]

On 24 August 2024, an explosion outside a synagogue in southern French – deemed a terrorist attack – injured a police officer.[208] The following day, a Jewish woman filed a complaint with French police that a man with a knife approached her on a Paris street, threatening to "kill Jews".[209] In response to the synagogue explosion, a "citizen rally to say no to antisemitism" was held.[210] French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin denounced the surge in antisemitism.[211] Following these attacks, some Jews began to express concerns about the future of Jews in France.[212]

On 5-6 January 2025, At least 10 Jewish homes, businesses, and a synagogue in Paris and Rouen have been vandalized with antisemitic symbols, including swastikas. Some of the graffiti praised Hitler, while others said antisemitic slogans, such as "Jews pedophiles, rapists to be gassed".[213]

Impact and analyses

[edit]New antisemitism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. Find sources: "new antisemitism" France – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) |

Since 2000, France has experienced "an explosion of antisemitism, unprecedented since the Second World War", according to Timothy Peace. Statistics for assaults, attacks on property, and desecration (such as in cemeteries) have increased. Antisemitism in the form of public expression (chants, slogans and placards with "Death to the Jews" and so on) and tensions in public places such as schools have mounted. As a result, the Jewish community is becoming increasingly concerned and fearful; some parents have removed their children from schools, and a record number have been leaving France and emigrating to Israel or other countries. The rise in incidents since 2000 has resulted in numerous books, press, and other media coverage, and gave rise to a debate about a "new antisemitism",[214] whether it exists in France, and if so, who is responsible for committing such acts, and why.[215]

Emigration

[edit]Since 2010 or so, more French Jews have been moving to Israel in response to rising antisemitism in France.[5]

Threats and violence from radicalized Islamists have caused heightened security concerns for Jews in France, as well as schools, religious institutions, and other gathering places. The situation is causing many Jews to reevaluate their future in France.[216]

Increasing attacks in France such as the pro-Palestinian demonstrations in 2014 morphed into attacks on the Jewish community as well as individual attacks have affected the sense of personal security among Jews in France. One-third of all French Jews who have emigrated to Israel since its founding in 1948 have done so in the ten years following 2009.[217]

This is of great concern to the French government, which has been both tracking incidents and speaking out against what appears to be a rising tide of antisemitism in the country.[218] Statistics compiled from various sources showed a leap of 74% in antisemitic acts in France in 2018, and a further 27% rise the year following.[219]

See also

[edit]- France–Israel relations

- Antisemitic publications in France

- Antisemitism in 21st-century France

- Antisemitism in Spain

- Antisemitism in Christianity

- Catholic Church and Judaism

- Catholic Church and Nazi Germany during World War II

- French Fourth Republic

- French nationalism

- French Third Republic

- German occupation of France

- History of far-right movements in France

- History of the Jews in France

- Jewish disabilities (medieval law)

- Jewish Museum of Belgium shooting

- Law of 3 October 1940 on the Status of Jews

- Mais qui?

- Maurice Papon

- Pope Pius XII and the Holocaust

- Pursuit of Nazi collaborators

- Religious antisemitism

- Rene Bousquet

- Strasbourg Cathedral bombing plot

- The Holocaust in France

- Toulouse and Montauban shootings

- Vichy anti-Jewish legislation

- Vichy Holocaust collaboration timeline

- Zone libre

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ See various essays in Birnbaum (2017)

- ^ Weekly magazine of racialist action against occult forces: in French, Hebdomadaire d'action racique[sic] contre les forces occultes. Not to be confused with the 1789 newspaper of the same name.

- Footnotes

- ^ a b "France". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ Blumenkranz, Bernhard (1972). Histoire des Juifs en France. Toulouse: Privat. p. 376.

- ^ a b "Le régime de Vichy: Le Bilan de la Shoah en France" [The Vichy regime: The balance sheet of the Shoah in France]. bseditions.fr. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b Croes, Marnix. "The Holocaust in the Netherlands and the Rate of Jewish Survival" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017.

- ^ a b Hall, John (25 January 2016). "Jews are leaving France in record numbers amid rising antisemitism and fears of more Isis-inspired terror attacks". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Almost 1 in 5 young French people think Jews leaving country would be good, CRIF finds". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 24 November 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ Benbassa 2001, p. 3.

- ^ a b Benbassa 2001, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Toni L. Kamins (2013). "1 A Short History of Jewish France". The Complete Jewish Guide to France. St. Martin's Publishing Group. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-4668-5281-5. OCLC 865113295.

- ^ a b Broydé, Isaac Luria; et al. (1906). "France". In Funk, Isaac Kaufmann; Singer, Isidore; Vizetelly, Frank Horace (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. V. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. hdl:2027/mdp.39015064245445. OCLC 61956716.

- ^ Benbassa 2001.

- ^ Grayzel, Solomon (July 1970). "The Beginnings of Exclusion". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 61 (1): 15–26. doi:10.2307/1453586. JSTOR 1453586.

- ^ Golb, Norman (1998). The Jews in medieval Normandy: a social and intellectual history. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58032-8. OCLC 36461619.

- ^ Published in Berliner's Magazin iii. 46–48, Hebrew part, reproducing Parma De Rossi MS. No. 563, 23; see also Jew. Encyc. v. 447, s.v. France.

- ^ a b "Jacob Ben Jekuthiel". JewishEncyclopedia.com.

- ^ Toni L. Kamins (2001). The Complete Jewish Guide to France. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312244491.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2009). A history of Christianity: the first three thousand years. London: Penguin. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-14-195795-1. OCLC 712795767.

- ^ Berliner's "Magazin," iii.; "Oẓar Ṭob," pp. 46–48.

- ^ "Rouen". encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores, iv. 137.

- ^ Chronicles of Adhémar of Chabannes ed. Bouquet, x. 152; Chronicles of William Godellus ib. 262, according to whom the event occurred in 1007 or 1008.

- ^ a b Bokenkotter, Thomas S. (2004). A concise history of the Catholic Church (Rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 155. ISBN 0385505841. OCLC 50242976.

- ^ Chronicles of Adhémar of Chabannes ed. Bouquet, x. 34

- ^ Riant, Paul Edouard Didier (1880). Inventaire Critique des Lettres Historiques des Croisades – 786–1100. Paris. p. 38.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Simonsohn, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Hoinacki, Lee (1996). El Camino : Walking to Santiago de Compostela. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0271016124. OCLC 33665024.

- ^ Cantor, Norman Frank (2015). Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture in England, 1089–1135. Princeton University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-4008-7699-0.

- ^ Nirenberg, David (31 January 2002). "The Rhineland Massacres of Jews in the First Crusade: Memories Medieval and Modern". Medieval Concepts of the Past. Cambridge University Press: 279–310. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139052320.014. ISBN 9780521780667.

- ^ Gilbert, M. (2010). The Routledge Atlas of Jewish History. Routledge. ISBN 9780415558105. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ David Nirenberg (2002). Gerd Althoff (ed.). Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography. Johannes Fried. Cambridge University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-521-78066-7.

- ^ Chazan, Robert (1996). European Jewry and the First Crusade. U. of California Press. pp. 55–60, 127. ISBN 9780520917767.

- ^ Shum Hebrew: שו"ם were the letters of the three towns as pronounced at the time in old French: Shaperra, Wermieza, and Magenzza.

- ^ Michael Costen, The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, p. 38

- ^ Mark Avrum Ehrlich (2009). Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-85109-873-6. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lindemann & Levy 2010, p. 75.

- ^ History of the reign of Charles VI, titled Chronique de Religieux de Saint-Denys, contenant le regne de Charles VI de 1380 a 1422, encompasses the king's full reign in six volumes. Originally written in Latin, the work was translated to French in six volumes by L. Bellaguet between 1839 and 1852.

- ^ Barkey, Karen; Katznelson, Ira (2011). "States, regimes, and decisions: why Jews were expelled from Medieval England and France" (PDF). Theory and Society. 40 (5): 475–503. doi:10.1007/s11186-011-9150-8. ISSN 0304-2421. S2CID 143634044.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Stéphane & Gualde 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 421. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Hertzberg, Arthur and Hirt-Manheimer, Aron. Jews: The Essence and Character of a People, HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, p. 84. ISBN 0-06-063834-6

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 420. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Lindsey, Hal (1990). The Road to Holocaust. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-553-34899-6.

- ^ Foa 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Kantor 2005, p. 203 1349 The Black Death massacres swept across Europe. ... The Jews were savagely attacked and massacred, by sometimes hysterical mobs – normal social order had ...

- ^ Marshall 2006, p. 376 The period of the Black Death saw the massacre of Jews across Germany, and in Aragon, and Flanders

- ^ a b Gottfried 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Durant 1953, pp. 730–731.

- ^ a b c d Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003). Saracens, Demons, and Jews: making monsters in Medieval art. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Kamins, Toni (20 March 2015). "From Notre Dame to Prague, Europe's anti-Semitism is literally carved in stone". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. New York. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019.

- ^ Aston 2000, pp. 72–89.

- ^ Hyman & Sorkin 1998, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Voltaire 1829, p. 493.

- ^ a b Birnbaum 2017, Introduction.

- ^ Morin 1989, pp. 71–122.

- ^ Feuerwerker 1965.

- ^ Sagnac 1899, p. 209.

- ^ Jack R. Censer; Lynn Hunt (27 September 1791). "Admission of Jews to Rights of Citizenship". Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Retrieved 7 November 2021., as compiled from: Hunt, Lynn (1996). The French Revolution and Human Rights: A Brief Documentary History. The Bedford series in history and culture. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 99–101. ISBN 9780312108021. OCLC 243853552.

- ^ Wein, Berel (1990). Triumph of Survival: The Story of the Jews in the Modern Era, 1650–1990. Jewish history, a trilogy, 3. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Shaar Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4226-1514-0. OCLC 933777867.

- ^ Barry Edward O'Meara (1822). "Napoleon in Exile". Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "New letters of Napoleon I". 1898. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Benbassa 2001, p. 209.

- ^ a b Poliakov 1981.

- ^ Whyte, George R. (2005). The Dreyfus Affair: A Chronological History. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-230-58450-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Schor 2005, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Coston 1979, p. 730.

- ^ "panama". www.ak190x.de.

- ^ a b Anna Yeatman; Charles Barbour; Phillip Hansen; Magdalena Zolkos (2011). Action and Appearance: Ethics and the Politics of Writing in Hannah Arendt. A&C Black. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4411-0173-0. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ Arendt, Hannah (21 March 1973). The Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 95–99. ISBN 0-15-670153-7. OCLC 760643287.

- ^ Guy Canivet, first President of the Supreme Court, Justice from the Dreyfus Affair, p. 15.

- ^ Winock, Michel (1971). "Édouard Drumont et l'antisémitisme en France avant l'affaire Dreyfus". Esprit. 403 (5): 1085–1106. JSTOR 24261978.

- ^ Duclert, Vincent (2018). L'affaire Dreyfus [The Dreyfus Affair] (in French). La Découverte. p. 95. ISBN 9782348040856.

- ^ Sjzakowski, Zosa (1961). "French Jews during the Revolution of 1830 and the July Monarchy". Historia Judaica. Vol. 22. pp. 116–120. OCLC 460467731. as quoted in Wilson (2007) p. 540

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Stephen (2007) [1st pub. Rutherford: 1982]. "Antisemitism in France at the Time of the Dreyfus Affair". In Strauss, Herbert A. (ed.). Hostages of Modernization: Germany, Great Britain, France. Liverpool scholarship online. Oxford: Littman library of Jewish civilization. ISBN 978-1-8003-4099-2. OCLC 1253400456.

- ^ Tombs 2014, p. 475.

- ^ Bopf, Britta (2004). 'Arisierung' in Köln: Die wirtschaftliche Existenzvernichtung der Juden 1933–1945. Cologne: Emons Verlag Köln. ISBN 389705311X. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Shoah Resource Center. "Aryanization" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Confiscation of Jewish Property in Europe, 1933–1945 New Sources and Perspectives Symposium Proceedings" (PDF). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Center For Advanced Holocaust Studies. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

Particularly impressive and equally disturbing is the robbers' effort to ensure that property confiscation was carried out by 'legal' means through a vast array of institutions and organizations set up for this purpose. The immensely bureaucratic nature of the confiscation process emerges from the vast archival trail that has survived. Arguments that no one knew about the Jews' fate become untenable once it is clear how many people were involved in processing their property. 'Legal' measures often masked theft, but blatant robbery and extortion through intimidation and physical assault were also commonplace.