Dyfnwal, King of Strathclyde

| Dyfnwal | |

|---|---|

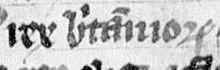

Dyfnwal's title as it appears on 29r of Paris Bibliothèque Nationale Latin 4126 (the Poppleton manuscript): "rex Britanniorum".[1] | |

| King of Strathclyde | |

| Successor | Owain ap Dyfnwal |

| Died | 908-915 |

| Issue | probably Owain ap Dyfnwal |

| Father | Uncertain, possibly Rhun ab Arthgal or Eochaid ab Rhun |

Dyfnwal (died 908×915) was King of Strathclyde.[note 1] Although his parentage is unknown, he was probably a member of the Cumbrian dynasty that is recorded to have ruled the Kingdom of Strathclyde immediately before him. Dyfnwal is attested by only one source, a mediaeval chronicle that places his death between the years 908 and 915.

Ancestry

Dyfnwal's parentage is uncertain. No historical source accords him a patronym.[6] He could have been a son of Rhun ab Arthgal,[7] the last identifiable King of Strathclyde before Dyfnwal.[8] Rhun was a member of the long-reigning Cumbrian dynasty of Strathclyde. He is the last monarch to be named by a pedigree preserved within a collection of tenth-century Welsh genealogical material known as the Harleian genealogies.[9]

A certain son of Rhun was Eochaid, a man who seems to have possessed a stake in the Scottish kingship before falling from power in the last decades of the ninth century.[10] It is unknown if Eochaid actually ruled the Kingdom of Strathclyde, although it is possible.[11] If Dyfnwal was not a son of Rhun, another possibility is that he descended from Eochaid:[12] either as a son[13] or grandson. Alternately, Dyfnwal could have represented a more distant branch of the same dynasty.[14] If Dyfnwal was indeed a son of Eochaid, a sister of his could have been Eochaid's apparent daughter, Land, the wife of Niall Glúndub mac Áeda attested by the twelfth-century Banshenchas.[15]

Expansion

Rhun's father, Arthgal ap Dyfnwal, ruled the Kingdom of Al Clud. In the 870s, the kingdom's principal citadel—the eponymous fortress of Al Clud ("Rock of the Clyde")—fell to the Irish-based Scandinavian kings Amlaíb and Ímar.[16] Thereafter, the kingdom's capital seems to have relocated up the River Clyde to the vicinity of Govan[17] and Partick.[18] The relocation is partly exemplified by a shift in royal terminology. Until the fall of Al Clud, for example, the rulers of the realm were styled after the fortress; whereas following the loss of this site, the Kingdom of Al Clud came to be known as the Kingdom of Strathclyde in consequence of its reorientation towards Ystrad Clud (Strathclyde), the valley of the River Clyde.[19][note 2]

At some point after the loss of Al Clud, the Kingdom of Strathclyde appears to have undergone a period of expansion.[21] Although the precise chronology is uncertain, by 927 the southern frontier appears to have reached the River Eamont, close to Penrith.[22] The catalyst for this southern extension may have been the dramatic decline of the Kingdom of Northumbria at the hands of conquering Scandinavians,[23] and the expansion may have been facilitated by cooperation between the Cumbrians and insular Scandinavians in the late ninth- and early tenth century.[24][note 3] Amiable relations between these powers may be evidenced by the remarkable collection of contemporary Scandinavian-influenced sculpture at Govan.[26]

Attestation

After Eochaid's career, the next notice of the Cumbrian realm is the record of Dyfnwal's death preserved by the ninth- to twelfth-century Chronicle of the Kings of Alba.[27] This is Dyfnwal's only attestation, and his appearance in this source could confirm that he was indeed related to the earlier rulers of Strathclyde.[28] In any case, one particular passage of the chronicle notes the deaths of five kings during the reign of Dyfnwal's Scottish counterpart, Custantín mac Áeda, King of Alba. Dyfnwal is the second of these five; the king before him is Cormac mac Cuilennáin; the ones after him are Domnall mac Áeda, Flann Sinna mac Maíl Sechnaill, and Niall Glúndub.[29][note 4] Although Dyfnwal's death is not specifically dated by the chronicle, the context of the passage suggests that it took place in 908×915.[31] Therefore, if the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba is to be believed, Dyfnwal died no later than 915.[32]

Successor

Dyfnwal appears to have been the father of Owain ap Dyfnwal,[33] a man who succeeded him as King of Strathclyde.[34] Dyfnwal's descendants are recorded to have ruled the Kingdom of Strathclyde into eleventh century.[35]

The personal name Dyfnwal was commonly employed by the Cumbrian royal dynasty. This name lays behind the place name of Dundonald/Dundonald Castle (grid reference NS3636034517), derived from the British *Din Dyfnwal. Although no Cumbrian monarch can be specifically linked to this location, any one of those named Dyfnwal could be the eponym.[36] Another place that could have been named after any of these like-named kings is Cardonald (grid reference NS5364).[37]

Notes

- ^ Since the 1990s, academics have accorded Dyfnwal various personal names in English secondary sources: Donald,[2] Donevaldus,[3] Dyfnwal,[4] and Dynwal.[5]

- ^ Either Arthgal or Rhun could have been the first monarch to rule the reconstructed realm of Strathclyde.[20]

- ^ The expansion of the Cumbrian kingdom may be perceptible in some of the place names of southern Scotland and northern England.[25]

- ^ The fact that the chronicle renders Domnall's kingdom as elig, a term which can be mistakenly interpreted as an abbreviation of eligitur ("he was selected"), has led to the erroneous belief that the ruling Alpínid dynasty of Alba inserted a member of its own—an otherwise unknown brother of Custantín named Domnall—to succeed Dyfnwal.[30]

Citations

- ^ Hudson (1998) p. 150; Skene (1867) p. 9; Lat. 4126 (n.d.) fol. 29v.

- ^ Hudson (2002); Hudson (1998).

- ^ Hudson (1994).

- ^ Clarkson (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b); Oram (2011); Clarkson (2010); Broun (2004b); Dumville, D (2000); Hudson (1994).

- ^ Hudson (1994).

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 4.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. genealogical tables; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Clarkson (2010) chs. genealogical tables, 9 ¶ 4; Broun (2004b) p. 135 tab.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 12.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. genealogical tables, 1 ¶ 23, 1 n. 56, 2 ¶¶ 21–22, 3 ¶ 19; Edmonds (2014) p. 201; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 571; Clarkson (2010) chs. genealogical tables, introduction ¶ 12, 2 ¶ 35–36, 4 ¶ 44, 8 ¶ 23, 9 ¶ 4; Bartrum (2009) p. 642; Woolf (2007) p. 28; Charles-Edwards (2006) p. 324 n. 1; Broun (2004b) p. 117; Ó Corráin (1998a) § 38; Ó Corráin (1998b) p. 331; Dumville, DN (1999) p. 110; Woolf (1998) pp. 159–160, 160–161 n. 61; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) p. 134; Hudson (1994) pp. 72, 110; Macquarrie (1986) p. 21; Anderson (1922) pp. clvii–clviii; Phillimore (1888) pp. 172–173; Skene (1867) p. 15.

- ^ Oram (2011) ch. 2.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 12.

- ^ Hudson (1998) p. 157 n. 39.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 4; Hudson (1994) pp. 56, 72, 173 genealogy 6.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 4.

- ^ Bartrum (2009) p. 286; Clancy (2006a); Bhreathnach (2005) p. 270; Hudson (2004); Hudson (1994) pp. 56, 171 genealogy 4, 173 genealogy 6, 174 n. 6; Dobbs (1931) p. 188.

- ^ Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 5–6; Edmonds (2015) p. 44; Edmonds (2014) p. 200; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 480; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 21; Clarkson (2012b) ch. 11 ¶ 46; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 20; Davies (2009) p. 73; Downham (2007) pp. 66, 142, 162; Clancy (2006b); Forsyth (2005) p. 32; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 8.

- ^ Foley (2017); Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 5, 7; Clarkson (2014) chs. 1 ¶ 23, 3 ¶ 11–12; Edmonds (2014) p. 201; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 480–481; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 23; Clarkson (2012b) ch. 11 ¶ 46; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 22; Davies (2009) p. 73; Oram (2008) p. 169; Downham (2007) p. 169; Clancy (2006b); Driscoll, S (2006); Forsyth (2005) p. 32; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 8, 10; Driscoll, ST (2003) pp. 81–82; Hicks (2003) pp. 32, 34; Driscoll, ST (2001a); Driscoll, ST (2001b); Driscoll, ST (1998) p. 112.

- ^ Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 5, 7; Clarkson (2014) ch. 3 ¶ 13; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 23; Clarkson (2012b) ch. 11 ¶ 46; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 22; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Driscoll, ST (2015) p. 5; Clarkson (2014) ch. 3 ¶ 11; Edmonds (2014) pp. 200–201; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 23; Clarkson (2012b) ch. 11 ¶ 46; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 26; Downham (2007) p. 162 n. 158; Clancy (2006b); Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 8, 10; Hicks (2003) pp. 15, 16, 30.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. 1 ¶ 23, 3 ¶ 18.

- ^ Dumville, DN (2018) p. 118; Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 6–7; Edmonds (2015) p. 44; James (2013) pp. 71–72; Parsons (2011) p. 123; Davies (2009) p. 73; Downham (2007) pp. 160–161, 161 n. 146; Woolf (2007) p. 153; Breeze (2006) pp. 327, 331; Clancy (2006b); Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 9–10; Hicks (2003) pp. 35–38, 36 n. 78.

- ^ Dumville, DN (2018) pp. 72, 110, 118; Edmonds (2015) pp. 44, 53, 62; Charles-Edwards (2013a) p. 20; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 481; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Parsons (2011) p. 138 n. 62; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 10; Davies (2009) p. 73, 73 n. 40; Downham (2007) p. 165; Woolf (2007) p. 154; Clancy (2006b); Todd (2005) p. 96; Hicks (2003) pp. 35–38; Stenton (1963) p. 328.

- ^ Lewis (2016) p. 15; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 481–482; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Breeze (2006) pp. 327, 331; Hicks (2003) pp. 35–38, 36 n. 78; Woolf (2001); Macquarrie (1998) p. 19; Fellows-Jensen (1991) p. 80.

- ^ Evans (2015) pp. 150–151; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 481–482.

- ^ James (2013) p. 72; James (2011); James (2009) p. 144, 144 n. 27; Millar (2009) p. 164.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 482; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 24; Downham (2007) pp. 162, 170.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 § 4; Downham (2007) p. 163.

- ^ Hudson (1998) p. 157 n. 39.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 13, 4 n. 11; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶¶ 4, 17; Downham (2007) pp. 163–164; Woolf (2007) pp. 126–128, 157; Broun (2004b) pp. 132–133; Davidson (2002) pp. 129 n. 96, 130; Hudson (2002) p. 37; Dumville, D (2000) p. 77; Hudson (1998) pp. 140, 150, 156–157, 156 n. 38, 157 nn. 39–42; Broun (1997) pp. 118–119 n. 35; Hudson (1994) pp. 56, 71, 174 n. 5; Anderson (1922) pp. 445–446; Skene (1867) p. 9.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 137; Clarkson (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 13; Clancy (2011) p. 373; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 17; Downham (2007) pp. 163–164; Woolf (2007) p. 157; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2007) p. 99; Broun (2004a); Broun (2004b) pp. 132–133; Davidson (2002) p. 129, 129 n. 96; Hudson (1998) p. 140; Hudson (1994) p. 71.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 163; Davidson (2002) p. 130.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 14.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) chs. genealogical tables, 1 ¶ 13, 4 ¶ 14; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Clarkson (2010) chs. genealogical tables, 9 ¶ 17; Broun (2004b) p. 135 tab.; Hudson (1994) pp. 72, 173 genealogy 6.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 17; Hudson (1994) p. 72.

- ^ Broun (2004b) p. 136.

- ^ Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 7.

- ^ Hicks (2003) p. 147, 147 n. 20.

References

Primary sources

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd. OL 14712679M.

- Dobbs, ME, ed. (1931). "The Ban-Shenchus". Revue Celtique. 48: 163–234.

- Phillimore, E (1888). "The Annales Cambriæ and Old-Welsh Genealogies From Harleian MS 3859". Y Cymmrodor. 9: 141–183.

- Hudson, BT (1998). "The Scottish Chronicle". Scottish Historical Review. 77 (2): 129–161. doi:10.3366/shr.1998.77.2.129. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530832.

- Lat. 4126. n.d.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1867). Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots, and Other Early Memorials of Scottish History. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. OL 23286818M.

Secondary sources

- Bartrum, PC (2009) [1993]. A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to About A.D. 1000. The National Library of Wales.

- Bhreathnach, E (2005). The Kingship and Landscape of Tara. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Breeze, A (2006). "Britons in the Barony of Gilsland, Cumbria". Northern History. 43 (2): 327–332. doi:10.1179/174587006X116194. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X. S2CID 162343198.

- Broun, D (1997). "Dunkeld and the Origin of Scottish Identity". The Innes Review. 48 (2): 112–124. doi:10.3366/inr.1997.48.2.112. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Broun, D (2004a). "Constantine II (d. 952)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6115. Retrieved 13 June 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Broun, D (2004b). "The Welsh Identity of the Kingdom of Strathclyde c.900–c.1200". The Innes Review. 55 (2): 111–180. doi:10.3366/inr.2004.55.2.111. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Charles-Edwards, T, ed. (2006). The Chronicle of Ireland. Translated Texts for Historians. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-959-8.

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013a). "Reflections on Early-Medieval Wales". Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion. 19: 7–23. ISSN 0959-3632.

- Charles-Edwards, TM (2013b). Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. The History of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clancy, TO (2006a). "Eochaid son of Rhun". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 704–705. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Clancy, TO (2006b). "Ystrad Clud". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1818–1821. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Clancy, TO (2011). "Gaelic in Medieval Scotland: Advent and Expansion: Sir John Rhys Memorial Lecture". Proceedings of the British Academy. 167. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197264775.003.0011 – via British Academy Scholarship Online.

- Clarkson, T (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons and Southern Scotland (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-02-3.

- Clarkson, T (2012a) [2011]. The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels and Vikings (EPUB). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-907909-01-6.

- Clarkson, T (2012b) [2008]. The Picts: A History (EPUB). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-907909-03-0.

- Clarkson, T (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age (EPUB). Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-907909-25-2.

- Davidson, MR (2002). Submission and Imperium in the Early Medieval Insular World (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/23321.

- Davies, JR (2009). "Bishop Kentigern Among the Britons". In Boardman, S; Davies, JR; Williamson, E (eds.). Saints' Cults in the Celtic World. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 66–90. ISBN 978-1-84383-432-8. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Downham, C (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Driscoll, S (2006). "Govan". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 839–841. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Driscoll, ST (1998). "Church Archaeology in Glasgow and the Kingdom of Strathclyde" (PDF). The Innes Review. 49 (2): 95–114. doi:10.3366/inr.1998.49.2.95. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Driscoll, ST (2001a). "Dumbarton". In Lynch, M (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Driscoll, ST (2001b). "Govan". In Lynch, M (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Driscoll, ST (2003). "Govan: An Early Medieval Royal Centre on the Clyde". In Breeze, DJ; Clancy, TO; Welander, R (eds.). The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph Series. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. pp. 77–83. ISBN 0903903229.

- Driscoll, ST (2015). "In Search of the Northern Britons in the Early Historic Era (AD 400–1100)". Essays on the Local History and Archaeology of West Central Scotland. Resource Assessment of Local History and Archaeology in West Central Scotland. Glasgow: Glasgow Museums. pp. 1–15.

- Dumville, D (2000). "The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba". In Taylor, S (ed.). Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297: Essays in Honour of Marjorie Ogilvie Anderson on the Occasion of Her Ninetieth Birthday. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 73–86. ISBN 1-85182-516-9.

- Dumville, DN (1999) [1993]. "Coroticus". In Dumville, DN (ed.). Saint Patrick, A.D. 493–1993. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 107–115. ISBN 978-0-85115-733-7.

- Dumville, DN (2018). "Origins of the Kingdom of the English". In Naismith, R; Woodman, DA (eds.). Writing, Kingship and Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–121. doi:10.1017/9781316676066.005. ISBN 978-1-107-16097-2.

- Edmonds, F (2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". Scottish Historical Review. 93 (2): 195–216. doi:10.3366/shr.2014.0216. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Edmonds, F (2015). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde". Early Medieval Europe. 23 (1): 43–66. doi:10.1111/emed.12087. eISSN 1468-0254. S2CID 162103346.

- Evans, NJ (2015). "Cultural Contacts and Ethnic Origins in Viking Age Wales and Northern Britain: The Case of Albanus, Britain's First Inhabitant and Scottish Ancestor" (PDF). Journal of Medieval History. 41 (2): 131–154. doi:10.1080/03044181.2015.1030438. eISSN 1873-1279. ISSN 0304-4181. S2CID 154125108.

- Ewart, G; Pringle, D; Caldwell, D; Campbell, E; Driscoll, S; Forsyth, K; Gallagher, D; Holden, T; Hunter, F; Sanderson, D; Thoms, J (2004). "Dundonald Castle Excavations, 1986–93". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 26 (1–2): i–x, 1–166. eISSN 1766-2028. ISSN 1471-5767. JSTOR 27917525.

- Fellows-Jensen, G (1991). "Scandinavians in Dumfriesshire and Galloway: The Place-Name Evidence" (PDF). In Oram, RD; Stell, GP (eds.). Galloway: Land and Lordship. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 77–95. ISBN 0-9505994-6-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Foley, A (2017). "Strathclyde". In Echard, S; Rouse, R (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1. doi:10.1002/9781118396957.wbemlb665. ISBN 9781118396957.

- Forsyth, K (2005). "Origins: Scotland to 1100". In Wormald, J (ed.). Scotland: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 9–37. ISBN 0-19-820615-1. OL 7397531M.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Hicks, DA (2003). Language, History and Onomastics in Medieval Cumbria: An Analysis of the Generative Usage of the Cumbric Habitative Generics Cair and Tref (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/7401.

- Hudson, BT (1994). Kings of Celtic Scotland. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29087-3. ISSN 0885-9159. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Hudson, BT (2002). "The Scottish Gaze". In McDonald, R (ed.). History, Literature, and Music in Scotland, 700–1560. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 29–59. ISBN 0-8020-3601-5.

- Hudson, BT (2004). "Niall mac Áeda [Niall Glúndub] (c.869–919)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20077. Retrieved 15 August 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- James, AG (2009). "Review of P Cavill; G Broderick, Language Contact in the Place-Names of Britain and Ireland" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 3: 135–158. ISSN 2054-9385.

- James, AG (2011). "Dating Brittonic Place-Names in Southern Scotland and Cumbria" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 5: 57–114. ISSN 2054-9385.

- James, AG (2013). "P-Celtic in Southern Scotland and Cumbria: A Review of the Place-Name Evidence for Possible Pictish Phonology" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 7: 29–78. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Lewis, SM (2016). "Vikings on the Ribble: Their Origin and Longphuirt". Northern History. 53 (1): 8–25. doi:10.1080/0078172X.2016.1127570. eISSN 1745-8706. ISSN 0078-172X. S2CID 163354318.

- Macquarrie, A (1986). "The Career of Saint Kentigern of Glasgow: Vitae, Lectiones and Glimpses of Fact". The Innes Review. 37 (1): 3–24. doi:10.3366/inr.1986.37.1.3. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Macquarrie, A (1998) [1993]. "The Kings of Strathclyde, c. 400–1018". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ (eds.). Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN 0-7486-1110-X.

- McGuigan, N (2015). Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850–1150 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7829.

- Millar, RM (2009). "Review of OJ Padel; DN Parsons, A Commodity of Good Names: Essays in Honour of Margaret Gelling, Donington" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 3: 162–166. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Oram, RD (2008). "Royal and Lordly Residence in Scotland c 1050 to c 1250: An Historiographical Review and Critical Revision". The Antiquaries Journal. 88: 165–189. doi:10.1017/S0003581500001372. eISSN 1758-5309. hdl:1893/2122. ISSN 0003-5815. S2CID 18450115.

- Oram, RD (2011) [2001]. The Kings & Queens of Scotland. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7099-3.

- Ó Corráin, D (1998a). "The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century". Chronicon: An Electric History Journal. 2. ISSN 1393-5259.

- Ó Corráin, D (1998b). "The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century". Peritia. 12: 296–339. doi:10.1484/j.peri.3.334. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Parsons, DN (2011). "On the Origin of 'Hiberno-Norse Inversion-Compounds'" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 5: 115–152. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Stenton, F (1963). Anglo-Saxon England. The Oxford History of England (2nd ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press. OL 24592559M.

- Todd, JM (2005). "British (Cumbric) Place-Names in the Barony of Gilsland, Cumbria" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society. 5: 89–102. doi:10.5284/1032950.

- Williams, A; Smyth, AP; Kirby, DP (1991). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain: England, Scotland and Wales, c.500–c.1050. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Woolf, A (1998). "Pictish Matriliny Reconsidered". The Innes Review. 49 (2): 147–167. doi:10.3366/inr.1998.49.2.147. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Woolf, A (2001). "Anglo-Scottish Relations: 1. 900–1100". In Lynch, M (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Woolf, A (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

Dyfnwal Died: 908×915 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Unknown Last known title holder: Rhun ab Arthgal1 | King of Strathclyde | Succeeded by Owain ap Dyfnwal |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. It is possible that Rhun's son, Eochaid, held the kingship after Rhun. | ||

- v

- t

- e

- Arthgal

- Rhun

- Eochaid

- Dyfnwal

- Owain

- Dyfnwal

- Rhydderch

- Máel Coluim

- Owain

- Owain Foel

- Máel Coluim

- Uncertain kings are italicised.