María de la Ossa de Amador

María de la Ossa de Amador | |

|---|---|

de la Ossa de Amador in 1913 | |

| First Lady of Panama | |

| In office February 20, 1904 – October 1, 1908 | |

| President | Manuel Amador Guerrero |

| Preceded by | Position Created |

| Succeeded by | Josefa Jované Aguilar y Távara |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Manuela María Maximiliano de la Ossa Escobar (1855-03-02)2 March 1855 Sahagún, Bolívar State, Republic of New Granada |

| Died | 5 July 1948(1948-07-05) (aged 93) Charlotte, North Carolina, United States |

| Spouse | Manuel Amador Guerrero (m. 1872–1909; his death) |

| Children | Raúl Arturo Guerrero Elmira María Guerrero de Ehrman |

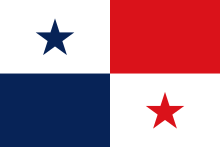

| Known for | creating the first Flag of Panama and planning the bloodless revolution for Panama's Independence |

María de la Ossa de Amador (2 March 1855 – 5 July 1948) was the inaugural First Lady of Panama serving from February 1904 to October 1908. She was one of the creators of the original Panamanian flag and a member of the separatist movement which fought for Panamanian independence from Colombia. She is known as the "Mother of the Nation" and in the corregimiento Parque Lefevre a school was named in her honor. In 1953, for the nation's 50th anniversary, a stamp bearing the likeness of her and her husband was issued by the government of Panama.

Early life

Manuela María Maximiliano de la Ossa Escobar was born on 2 March 1855 in Sahagún, Chinú Province, Bolívar State (when it was part of the Republic of New Granada, now Córdoba Department, Colombia) to Manuela Escobar Arce and Jose Francisco de la Ossa Molina.[1][Notes 1]

Her father was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court for the Isthmus Department of Colombia[5][6] and her maternal grandfather and his brothers were signers of the Declaration of Independence of Panama from the Spanish Empire.[7] Her siblings included: Jerónimo (1847–1907), who wrote the National anthem of Panama;[6][8] Ramona (1849-prior to 1919)[9][Notes 2], who married the legislator Manuel C. Cervera;[12][13] Emilia (1850–1938), mother of Edwin Lefèvre, who was a women's rights advocate and later a writer;[6][14] José Francisco Ramón (1851–1852);[15][16] José Francisco (1856–1956), who served as Mayor of the Isthmus Department and later a Superior Court Judge;[17] Ricardo (1860–1907), who owned a Peruvian business;[18][19] and Manuela Augusta (1864–?),[20] who married Jose Guillermo Lewis Herrera.[21][11]

De la Ossa was raised in an era of rigid custom, where upper-class women were kept separate from society and trained in the arts of music and needlework, to prepare them for marriage and the domestic sphere.[14] She attended a convent school in Panama City and was educated by private tutors.[22] On 6 February 1872, she married Manuel Amador Guerrero,[4] as his second wife. Amador had a previous son, Manuel Encarnación Amador Terreros,[2] with his first wife, María de Jesús Terreros.[23][24] The couple had two children, Raúl Arturo, who as an adult was attached to the Panamanian consulate in New York City and Elmira María, who married William Ehrman, one of the owners of the Ehrman Banking Company.[2][23]

Independence movement

When the French company that owned the rights to build the Panama Canal went bankrupt, the United States bought the rights to build the canal in 1902.[25] Contentious negotiations with Colombia led the United States to back the separatist movement in Panama, believing that negotiations would be more favorable to American interests from a small, weak newly developing state.[26] To that end, Amador traveled to New York in September 1903 to work out how the United States was willing to support their separation movement.[27] He returned to Panama to put plans in motion[28] and asked his son, Manuel Encarnación to design the flag for the new nation. The design was completed on 1 November and de la Ossa and her sister-in-law Angélica Bergamonta de la Ossa, Jerónimo's wife,[3][29] purchased the blue, red, and white fabrics from three different warehouses in Panama City, so as not to arouse suspicion.[2] Having secured sufficient fabric to make two flags, the women worked through the night on 2 November using a portable sewing machine to complete the flag.[29] A third, smaller flag was made of the fabric remnants by María Emilia, Angélica's daughter[29][30] and the women were assisted by de la Ossa's domestic helper, Águeda.[31]

The U.S. naval ship USS Nashville arrived on the coastline on 2 November.[28] On 3 November 1903, word reached separatists in Panama City, that General Juan B. Tobar, was landing with the cruiser Cartagena and merchant ship Alexander Bixio from Colombia to the coastline near Colón. Leading a battalion of 500 soldiers, which included the Third Sharpshooter Battalion, Tobar was on the way to the capital. Fearing that if they were caught they would be executed, Amador, along with José Agustín Arango, Federico Boyd, and Manuel Espinosa Batista met to discuss the situation. Many of their colleagues decided to abandon the cause. De la Ossa suggested that her husband make contact with a trusted ally, Herbert G. Prescott, assistant superintendent of the Panama Railway, in hopes that Prescott could convince Superintendent James Shaler to help.[4][32] Prescott was at the time, the fiancé of María Emilia de la Ossa Bergamota, daughter of de la Ossa's brother Jerónimo.[27] When Amador went to speak with Prescott, de la Ossa left and met with Arango and Espinosa, husband of her cousin, to reassure them that the plans were proceeding and convince them to remain steadfast to the cause.[4]

De la Ossa's plan involved having Shaler convince Tobar to come to the capital, separating him from his troops. Once there, he would be captured and his troops bribed to return home.[32][33][31] When the plan successfully concluded,[33] one of the flags was hung from a balcony and the other was paraded through the streets on 3 November.[2][29] Upon securing Panama's independence, Amador was elected as the first constitutional President of Panama and de la Ossa became the inaugural First Lady. Their term began on 20 February 1904 and ended on 1 October 1908[23] with de la Ossa serving as the official hostess of the country. Her duties included providing official entertainments for dignitaries and meeting daily during the season with official guests.[22] Choosing not to seek re-election, Amador died soon after leaving office in 1909.[34] After her husband's death, de la Ossa traveled between visits to various family members in the United States and Europe. She was a proponent of women's education and had a strong belief in religion as providing a moral compass to guide women.[22] She lived in Paris until 1939, when she moved to Charlotte, North Carolina.[35] In 1935, Flag Day was first celebrated in her honor on 4 November and in 1941, Public Law 60 was passed by the National Assembly of Panama to recognize her contributions to the nation.[2]

Death and legacy

De la Ossa died on 5 July 1948, in Charlotte and her remains were buried in Panama.[35] She is known as the "Mother of the Nation" and in the corregimiento known as Parque Lefevre, a school was named in her honor.[3] Of the three flags made for the independence, one was destroyed by repeated use.[29] The small flag made by María Emilia was either hoisted on the flagpole of the first steamer to leave Panama for the United States to announce the success of the country's independence[30] or taken by María Emilia to New York, where it was exhibited in a shop and later a museum, before its whereabouts became unknown.[29] The third flag, which was retained by de la Ossa was later given as a gift to President Theodore Roosevelt and is believed to have been later donated to the Library of Congress.[29][2] In 1953, for the nation's 50th anniversary, a stamp bearing the likeness of her and her husband was issued by the government of Panama.[36]

Notes

- ^ Peréz gives her birth date as 1 March 1855,[2] as do other sources,[3] while Diez Castillo gives the date as 2 March 1855.[4] The latter date is used, based upon the statement in Mega: "Notario Público de este Departamento, compareció el Señor Doctor José Francisco de la Ossa, y expuso: que el día dos de Marzo de mil ochocientos cincuenta y cinco tuvo lugar en el distrito de Sahagun de la Provincia del Chinú (en el Estado soberano de Bolívar) el nacimiento de una niña a quien se ha puesto por nombre Manuela María Maximiliano, al ser bautizada, pero tan solo se le ha dejado el de María, que es hija legítima del exponente y de la señora Manuela Escobar..." (translation: Notary Public of this Department, Dr. José Francisco de la Ossa appeared, and explained that on March 2, one thousand eight hundred and fifty-five took place in the district of Sahagun of the Province of Chinú (in the sovereign State of Bolívar) the birth of a girl who was named Manuela María Maximiliano, when she was baptized, but only María has been left, who is the legitimate daughter of the exponent and of Mrs. Manuela Escobar).[1]

- ^ When settlement for their father's estate was requested in 1919, Ramona was not mentioned, thus it is probable that she died without issue prior to that time.[10] Francisco, Emelia, María, Manuela, and both Jerónimo and Ricardo’s widows were provided for in the final settlement.[11]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Mega 1946, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pérez 2016.

- ^ a b c López 2015.

- ^ a b c d Diez Castillo 2000.

- ^ White 1967, p. 142.

- ^ a b c Panamanian Baptisms 1850, p. 308.

- ^ Morris 1937, p. 150.

- ^ Martínez Ortega 1992, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Panamanian Baptisms 1849, p. 254.

- ^ The Panama Canal Record 1920, p. 328-329.

- ^ a b The Panama Canal Record 1920, p. 515.

- ^ Panamanian Baptisms 1875, p. 136.

- ^ Eustaquio Álvarez 2007, p. 47.

- ^ a b Lefevre de Wirz 2009.

- ^ Panamanian Baptisms 1852, p. 189.

- ^ Moreno 2017.

- ^ Pizzurno & Araúz 2000.

- ^ New York Passenger Lists 1888, p. 33.

- ^ Peruvian Death Registration 1907, p. 300.

- ^ New York Passenger Lists 1909.

- ^ New York City Municipal Deaths 1902.

- ^ a b c The Los Angeles Times 1913, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Arcia Jaramillo 2016.

- ^ Castro Stanziola 2002.

- ^ Harding 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Sanchez 2003, p. 53.

- ^ a b Ospina Peña 2017, p. XXV—El Plan B.

- ^ a b Harding 2006, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Guevara 2015.

- ^ a b The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat 1904, p. 5.

- ^ a b La Estrella de Panamá 2011.

- ^ a b Ospina Peña 2017, p. XXX—Los acontecimientos en Panamá.

- ^ a b Harding 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Delpar 2013, p. 11.

- ^ a b The Daily Times-News 1948, p. 3.

- ^ Stamp World 2017.

Bibliography

- Arcia Jaramillo, Ohigginis (9 March 2016). "El AND de Amador Guerrero" [The DNA of Amador Guerrero]. La Prensa (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Castro Stanziola, Harry (14 July 2002). "Globalizando los idiomas" [Globalizing Languages]. La Prensa (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Delpar, Helen (2013). "Amador Guerrero, Manuel". In Leonard, Thomas; Buchenau, Jurgen; Longley, Kyle; Mount, Graeme (eds.). Encyclopedia of U.S.-Latin American Relations. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-60871-792-7.

- Diez Castillo, Luis A. (1 September 2000). "María Ossa de Amador: revivida" [María Ossa de Amador: revived] (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Editora Panamá América. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Eustaquio Álvarez, Francisco (2007). Manual de lógica (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Universidad del Rosario. ISBN 978-958-8298-62-7.

- Harding, Robert C. (2006). The History of Panama. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33322-4.

- Guevara, Helkin (5 November 2015). "Historia de las primeras banderas panameñas y de la que no es 'original'" [History of the first Panamanian flags and of the one that is not 'original']. La Prensa (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Lefevre de Wirz, E.E.R. (30 January 2009). "Emilia Lefevre (de la Ossa)". Edificio Lefevre (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Casa Lefevre. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- López, Cecy (4 November 2015). "Doña María Ossa de Amador considerada la Madre de La Patria" [Doña María Ossa de Amador considered the Mother of the Homeland] (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Televisora Nacional. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Martínez Ortega, Aristides (1992). Las generaciones de poetas panameños (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Tareas. OCLC 28378848.

- Moreno, Roberto A. (2017). "José Francisco de la Ossa Escobar". Geneanet (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Mega, Pedro (1946). Noticias históricas de la Iglesia de la Merced: de la antigua y nueva Panamá de panameños notables del siglo XVIII y XIX (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Taller de The Star & Herald. OCLC 1543006.

- Morris, Harry Timothy (1937). "George Edwin Henry Lefèvre". 50-year Book: Lehigh 1891. Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Times Publishing Company. pp. 150–154. OCLC 28645827.

- Ospina Peña, Mariano (21 July 2017). Los Roosevelt, los magnates y Panama [Roosevelt, the Magnates and Panama] (in Spanish). Colombia: Así Sucedió. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Pérez, Yelina (4 November 2016). "Diez datos curiosos de María De La Ossa de Amado" [Ten curious facts about María De La Ossa de Amador]. Revista Mia (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: La Estrella de Panamá. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Pizzurno, Patricia; Araúz, Celestino Andrés (2000). "José Francisco de la Ossa" (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Editora Panamá América. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Sanchez, Peter M. (2003). "Panama: A "Hegemonized" Foreign Policy". In Hey, Jeanne A. K. (ed.). Small States in World Politics: Explaining Foreign Policy Behavior. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 53–74. ISBN 978-1-55587-943-3.

- White, James Terry (1967). The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. 32. New York, New York: James T. White & Company.

- "Joint Commission: Decisions of the Umpire". The Panama Canal Record. XIII (35). Balboa Heights, Canal Zone, Panama: The Panama Canal: 514–515. 14 April 1920. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "1953 Airmail – The 50th Anniversary of Panama Republic". Stamp World. Belize City, Belize: Belize Bank Limited. 2017. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Madam Maria Amador". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. 4 May 1913. p. 31. Retrieved 23 December 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New York City Municipal Deaths, Manhattan death certificates, 1866–1919: José Guillermo Lewis". FamilySearch. New York City, New York: Municipal Records Department. 22 September 1902. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "New York Passenger Lists 11 Aug 1888-7 Sep 1888: Mr. Ricardo de la Ossa". FamilySearch. Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 13 August 1888. NARA microfilm publication M237, Roll 524, passenger #101. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "New York Passenger Lists 1892–1924: Manuela de Lewis". FamilySearch. New York City, New York: Ellis Island Foundation. 8 November 1909. Passenger id=101715050277, frame 865. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Panamá, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, Bautismos 1844–1852: Emilia Luísa María Santiago de la Ossa". FamilySearch (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Parroquias Católicas. 26 May 1850. FHL film #760720, v9 e48, Certificate #3924. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "Panamá, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, Bautismos 1844–1852: José Francisco Ramón de la Ossa". FamilySearch (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Parroquias Católicas. 10 January 1852. FHL film #4033476, Certificate #7. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Panamá, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, Bautismos 1844–1852: Ramona Efremia María de la Ossa". FamilySearch (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Parroquias Católicas. 16 February 1849. FHL film #4033476, Certificate #31. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Panamá, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, Bautismos 1866–1889: Amanda María Cervera". FamilySearch (in Spanish). Panama City, Panama: Parroquias Católicas. 19 January 1875. FHL film #4813486, Certificate #422. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Perú, Registro Civil, Defunciones 1907 (Mar-Ago): Ricardo de la Ossa". FamilySearch (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Archivo General de la Nación. 5 March 1907. FHL film #4254303, image=20. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Semblanza y acción de Manuel Amador Guerrero" [Semblance and action of Manuel Amador Guerrero]. Panama City, Panama: La Estrella de Panamá. 9 November 2011. p. Spanish. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- "Widow of Panama's First President Dies at Charlotte". The Daily Times-News. Burlington, North Carolina. 6 July 1948. p. 3. Retrieved 23 December 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Women at Home and Abroad". The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, Louisiana. 9 February 1904. p. 5. Retrieved 23 December 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

| Honorary titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Position created | First Lady of Panama 1904–1908 | Succeeded by Josefa Jované de Obaldia |