| Odyssey | |

|---|---|

| Attributed to Homer | |

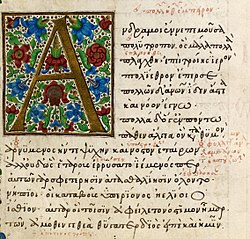

Oldest-known manuscript fragment of the Odyssey, produced in Ptolemaic Egypt during the 3rd century BC and unearthed in Medinet Ghoram | |

| Original title | Ὀδύσσεια |

| Translator | See translations of the Odyssey or English translations |

| Composed | c. 8th century BC |

| Language | Homeric Greek |

| Genre(s) | Epic |

| Form | Epic poem |

| Rhyme scheme | None |

| Lines | 12,109 |

| Preceded by | The Iliad |

| Metre | Dactylic hexameter |

| Full text | |

The Odyssey (/ˈɒdɪsi/;[1] Ancient Greek: Ὀδύσσεια, romanized: Odýsseia)[2] is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the Iliad, the Odyssey is divided into 24 books. It follows the heroic king of Ithaca, Odysseus, also known by the Latin variant Ulysses, and his homecoming journey after the ten-year long Trojan War. His journey from Troy to Ithaca lasts an additional ten years, during which time he encounters many perils and all of his crewmates are killed. In Odysseus's long absence, he is presumed dead, leaving his wife Penelope and son Telemachus to contend with a group of unruly suitors competing for Penelope's hand in marriage.

The Odyssey was first composed in Homeric Greek around the 8th or 7th century BC; by the mid-6th century BC, it had become part of the Greek literary canon. In antiquity, Homer's authorship was taken as true, but contemporary scholarship predominantly assumes that the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed independently, as part of long oral traditions. Given widespread illiteracy, the poem was performed for an audience by an aoidos or rhapsode.

Key themes in the epic include the ideas of nostos (νόστος; 'return', homecoming), wandering, xenia (ξενία; 'guest-friendship'), testing, and omens. Scholars discuss the narrative prominence of certain groups within the poem, such as women and slaves, who have larger roles than in other works of ancient literature. This focus is especially remarkable when contrasted with the Iliad, which centres the exploits of soldiers and kings during the Trojan War.

The Odyssey is regarded as one of the most significant works of the Western canon. The first English translation of the Odyssey was in the 16th century. Adaptations and re-imaginings continue to be produced across a wide variety of media. In 2018, when BBC Culture polled experts around the world to find literature's most enduring narrative, the Odyssey topped the list.

Background

[edit]Dating

[edit]Many suggestions have been made for dating composition of the Iliad and the Odyssey, but there is no consensus.[3] Richard Lamberton says that the epics "[straddled] the beginnings of widespread literacy" from the middle of the 5th-century BC,[4] but the poems' language can be dated to long before this period.[5] The Greeks began adopting a modified version of the Phoenician alphabet to create their own writing system during the eighth century BC;[3] if the Homeric poems were among the earliest products of that literacy, they would have been composed towards the late period of that century.[6][a]

According to Rudolf Pfeiffer, they were probably written down, but there is no evidence for their publishing or physical dissemination for consumption by a literate audience.[9][b] Dating is further complicated by the fact that the Homeric poems, or sections of them, were performed by rhapsodes for hundreds of years.[3]

Composition and authorship

[edit]Scholars agree that the Homeric epics developed as part of an oral tradition over hundreds of years.[11] In the early twentieth century, Milman Parry and Albert Lord demonstrated that they prominently contained the characteristics of oral poetry,[12][c] which would allow even an illiterate poet to improvise large poems,[14] composing them through speech.[12] Scholars do not agree on how the poems emerged from this tradition,[5] and it is not clear whether oral tradition can claim full credit for their composition.[15] In the nineteenth century, a series of related questions about the epics' authorship became known as the Homeric Question.[16] Sources from antiquity created mythic narratives to explain Homer.[17] Debate still persists today over many of the Homeric questions;[5] for example, concerning the compositional relationship between the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the largely lost poems of the Epic Cycle; about whether Homer lived and, if he did, when;[16] and whether the poems reflect any geographical, historical or cultural reality.[5] While Homer is today attributed as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, other texts have historically been attributed to him—for example, the Homeric Hymns.[18]

Textual reconstructions indicates the poems have taken many forms.[19] As live performance involves feedback, the content of the poem may even have varied from telling to telling.[18] This context is important for understanding and interpreting the epics,[20] and John Miles Foley said that performance is crucial part of their meaning.[21] Performance of epic poetry is a subject of both poems, with the Odyssey actually depicting professional singers like Phemius and Demodocus.[22] Applying these in-narrative performances to our understanding of the epics' performance might indicate that they were performed at the houses of distinguished families as part of banquets or dinners in the 2nd and early 1st millennia BC,[23][24] and that observers may have directed or participated in them.[23] They were probably recited—as in, not performed with music.[25]

Like the Iliad, the Odyssey is divided into twenty-four parts.[d] Early scholars suggested these correspond to the 24 letters of the Greek alphabet, but this is widely considered ahistorical.[27][e] The division was probably made long after the poem's composition but is generally accepted as part of the poem's modern structure.[29] There are many theories as to how they arose. Some suggest they were an authentic part of the oral tradition or invented by Alexandrian scholars.[30] Pseudo-Plutarch attributed the divisions to Aristarchus of Samothrace, but there is some evidence against this.[31][32] Some scholars connect the epics' segmentation to the tradition of performance, for example as a creation of rhapsodes.[33][34]

Both epics assume some knowledge of their audiences—for example, concerning the Trojan War. This strongly indicates that the epics were engaging with a pre-existing mythological tradition.[35] Arguments exist for either epic having been composed first; it is not clear.[36] While the Trojan War is an important element for both, the Odyssey does not directly reference any events from the Iliad's depiction of the war,[37][f] and they are generally considered to have formed independently from one another.[36]

Influences

[edit]

Scholars note strong influences from Near Eastern mythology and literature in the Odyssey.[39] Martin West notes substantial parallels between the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Odyssey.[40] Both Odysseus and Gilgamesh are known for traveling to the ends of the earth and on their journeys go to the land of the dead.[41] On his voyage to the underworld, Odysseus follows instructions given to him by Circe, who is located at the edges of the world and associated with solar imagery.[42] Like Odysseus, Gilgamesh gets directions on reaching the land of the dead from a divine helper: the goddess Siduri, who, like Circe, dwells by the sea at the ends of the earth, whose home is also associated with the sun. Gilgamesh reaches Siduri's house by passing through a tunnel underneath Mt. Mashu, the high mountain from which the sun comes into the sky.[43] West argues that the similarity of Odysseus's and Gilgamesh's journeys to the edges of the earth are the result of the influence of the Gilgamesh epic upon the Odyssey.[44] Classical folklorist Graham Anderson notes other patterns—the heroes of Odyssey and Gilgamesh meet women who can transform people into animals; are involved in the death of divine cattle; unhappily enjoy the presence of a "voluptuous lady in an other-worldly paradise" following a voyage through the underworld.[45]

Scholars have explored whether figures originate within the poem or belong to a tradition outside of it. Adrienne Mayor says that the Austrian paleontologist Othenio Abel made unfounded claims about the fifth-century BC philosopher Empedocles connecting the cyclops to prehistoric elephant skulls.[46] Whether the epic poem created, popularised, or simply retold the tale of Polyphemus is a long-standing dispute,[47] but Anderson says there is some amount of scholarly consensus that the story existed separately from the epic.[45] William Bedell Stanford notes there are some indications that Odysseus existed independently of Homer, although it is inconclusive.[48]

Geography

[edit]Scholars are divided on whether any of the places visited by Odysseus are real.[49] The events in the main sequence of the Odyssey (excluding Odysseus's embedded narrative of his wanderings) have been said to take place across the Peloponnese and the Ionian Islands.[50] Many have attempted to map Odysseus's journey, but largely agree that the landscapes—especially those described in books 9 to 11—include too many mythical elements to be truly mappable.[51] For instance, there are challenges ascertaining whether Odysseus's homeland of Ithaca is the same island that is now called Ithakē (modern Greek: Ιθάκη);[50] the same is true of the route described by Odysseus to the Phaeacians and their island of Scheria.[49] British classicist Peter Jones writes that the poem was likely updated many times by oral story-tellers across several centuries before it was written down, making it "virtually impossible" to say "in what sense [the poem] reflects a historical society or accurate geographical knowledge".[52] Modern scholars tend to explore Odysseus's journey metaphorically rather than literally.[53]

Synopsis

[edit]

Ten years after the Achaean Greeks won the Trojan War, Odysseus, king of Ithaca, has yet to return home from Troy. In his absence, 108 boorish suitors court his wife Penelope. Penelope tells them she will remarry when she is done weaving a shawl; however, she secretly unweaves it every night.

The goddess Athena, disguised first as Mentes then as Mentor, tells Odysseus's son Telemachus to seek news of his father. The two leave Ithaca and visit Nestor, who tells them that Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek army at Troy, was murdered soon after the war. Telemachus travels to Sparta to meet Agamemnon's brother Menelaus, who in turn describes his encounter with the shape-shifting god Proteus. Menelaus says he learned from Proteus that Odysseus is alive, but held captive by the nymph Calypso.

Athena petitions Zeus to rescue Odysseus, and Zeus sends Hermes to negotiate his release. As Odysseus leaves Calypso's island, Poseidon destroys his raft with a storm. The sea nymph Ino protects Odysseus as he swims to Scherie, home of the Phaeacians, and Athena leads the Phaeacian princess Nausicaä to recover him. In the court of Nausicaä's parents Arete and Alcinous, Odysseus excels at athletic games and is overcome with emotion when the bard Demodocus sings about the Trojan War. Odysseus reveals his identity and recounts his adventures following the war.

On leaving Troy, Odysseus's men unsuccessfully raided the Cicones. Afterward, on an island of lotus-eaters, they found intoxicating fruit which made them forget about reaching home. On another island, they were captured by the cyclops Polyphemus. Odysseus, deceptively calling himself "Nobody", escaped by intoxicating the cyclops and blinding him. However, he boastfully revealed his true identity while escaping, and Polyphemus asked his father Poseidon to take revenge.

Odysseus's crew nearly arrived in Ithaca, but were blown off course after opening a bag of winds they received from Aeolus. Afterwards, all but one of their ships were destroyed by giant cannibals called Laestrygonians. On the island of Aeaea, the witch-goddess Circe turned Odysseus's men into pigs. Hermes helped Odysseus resist Circe's magic using the herb moly, and Odysseus forced her to restore the crew's human forms. Odysseus and Circe then became lovers for a year until he left to continue home. Next, Odysseus traveled to the edge of Oceanus, where the living can speak with the dead. The spirit of the prophet Tiresias told Odysseus he would successfully return home, but must eventually undertake another journey. Odysseus also met the spirits of his mother Anticleia and former comrades Agamemnon and Achilles.

Odysseus's crew then sailed past the Sirens, whose enticing song lured sailors to their deaths. His crewmen plugged their ears with beeswax to avoid hearing them, while Odysseus tied himself to the ship's mast. Next, they navigated the narrow passage between the whirlpool Charybdis and the multi-headed monster Scylla. Finally, on the island of Thrinacia, Odysseus's men killed and ate sacred cattle belonging to the sun god Helios. Helios asked Zeus to punish them, which he did by destroying their last ship. Odysseus, the sole survivor, washed ashore on the island Ogygia. There he met Calypso, who took him captive as her lover until Hermes eventually intervened.

After hearing Odysseus's story, the Phaeacians take him to Ithaca, where Athena disguises him as an elderly beggar. Without knowing his identity, the swineherd Eumaeus offers him lodging and food. Telemachus returns home from Sparta, evading an ambush from the suitors. Odysseus reveals himself to his son and the two return home, where Odysseus's elderly dog Argos recognizes him through his disguise. The suitors mock and mistreat Odysseus in his own home. He and Telemachus hide the suitors' weapons in preparation for violent revenge. Odysseus also reencounters Penelope and her servant Eurycleia, who recognizes him from a scar on his feet.

Penelope announces she is ready to remarry, and that she will choose whoever wins an archery contest with Odysseus's bow. After each suitor fails to even string the bow, Odysseus successfully strings it and fires an arrow through a series of axe heads. Having won the contest, he kills the suitors; Telemachus also hangs a group of slaves who had sex with them. Odysseus reveals his identity to Penelope, who tests him by asking to move their bed. He correctly states that the bed, which he carved from the trunk of an olive tree, is immovable, and the two lovingly reunite.

The next day, after Odysseus reveals himself to his father Laertes, the families of the murdered suitors gather to get revenge. Athena intervenes and prevents further bloodshed.

Style

[edit]Structure

[edit]

The narrative opens in medias res; the preceding events are described through flashbacks and storytelling.[54]

In Classical Greece, some books or sections were provided with their own titles. Books 1 to 4, which focus on the perspective of Telemachus, are called the Telemachy.[55] Books 9 to 12, wherein Odysseus provides an account of his adventures, are called the Apologos or Apologoi.[53][56] Book 22 was known as Mnesterophonia (Mnesteres, 'suitors' + phónos, 'slaughter').[57] Book 22 is generally said to conclude the Greek Epic Cycle, but fragments remain of a lost sequel known as the Telegony.[58]

Debate exists over what constitutes the "original" Odyssey. Some scholars regard the Telemachy as a later additional while others note that later parts do not make sense without those books.[59] Likewise, the poem's ending has been the subject of debate since antiquity—Aristarchus of Samothrace and Aristophanes of Byzantium regarded the epic's real ending as lines 293–295 of book 23. Similar debates over the poem's ending occur today.[60]

Narrative and language

[edit]The epic has 12,109 lines composed in dactylic hexameter, sometimes called Homeric hexameter—a metre with six metrical feet.[61][62] The form of hexameter is catelectic, meaning that it lacks an expected syllable in the last foot. Each line has between twelve to seventeen syllable and generally forms a grammatically complete sentence.[26] The poems may have inherited some stylistic traditions but invented others.[63]

The narrative is primarily related through speech—that is, characters talking to themselves or to somebody else.[64] Consequently, they frequently serve as narrators alongside the Homeric narrator, and their speech is the primary method of characterisation.[65]

The language is simple, direct, and fast-paced.[66] It is also literary in style—the vocabulary was likely never the vernacular of any Greek population.[67] An important characteristic of the language is the Homeric simile. These are comparative metaphors that can be long[g] or short,[69] typically deriving from the natural world or everyday life. Irene de Jong describes them as "omnitemporal"—they may use the simple present tense, or the epic tense (blending past and present), or they may present a timeless truth (gnomic aorist).[70] Their functions vary; examples include characterisation and the reinforcement of theme.[71] Traditionally, the Homeric simile was regarded as a predecessor of European literary similes. This has been contested—for example by Oliver Taplin.[72] Modern scholars generally agree that the Homeric similes formed as part of the epics' oral tradition, but earlier writers sometimes said they were added by one or more later poets.[73]

An important element of Homeric texts is their use of epithets—in English, these are often translated as compound adjectives like much-nourished or much-nourishing.[74]

Themes and patterns

[edit]Homecoming

[edit]

Homecoming (Ancient Greek: νόστος, nostos) is a central theme of the Odyssey.[75] The Greek word nostos signifies both a homecoming voyage by sea and narratives involving the homecoming.[76][77] Classicist Agathe Thornton notes that nostos to the victorious Achaeans following the fall of Troy, but the narrator focuses on Odysseus and provides other Achaeans' homecomings as part of his narrative.[78]

Following Agamemnon's homecoming, his wife Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, kill Agamemnon. Agamemnon's son, Orestes kills Aegisthus for vengeance, paralleling the death of the suitors with the death of Aegisthus; Athena and Nestor famously use Orestes as an example for Telemachus, motivating him to action.[79] During Odysseus's trip to the underworld, Agamemnon tells him about Clytemnestra's betrayal. After reaching Ithaca, Athena transforms Odysseus into a beggar so he can test the loyalty of his wife Penelope.[80]

Agamemnon eventually praises Penelope for not killing Odysseus, and her faithfulness ensures Odysseus both fame and a successful homecoming compared to the other Achaeans. Agamemnon's failed homecoming caused his death; Achilles achieved fame but died and was denied homecoming.[81]

Wandering

[edit]Before Odysseus's arrival in Ithaca, only two of his adventures are described by the narrator. The rest of Odysseus's adventures are recounted by Odysseus himself. The two scenes described by the narrator are Odysseus on Calypso's island and Odysseus's encounter with the Phaeacians. These scenes are told by the poet to represent an important transition in Odysseus's journey: being concealed to returning home.[82]

Calypso's name comes from the Greek word kalúptō (καλύπτω), meaning 'to cover' or 'conceal', which is apt, as this is exactly what she does with Odysseus.[citation needed] Calypso keeps Odysseus concealed from the world and unable to return home. After leaving Calypso's island, the poet describes Odysseus's encounters with the Phaeacians—those who "convoy without hurt to all men"[83]—which represents his transition from not returning home to returning home.[82]

Also, during Odysseus's journey, he encounters many beings that are close to the gods. These encounters are useful in understanding that Odysseus is in a world beyond man and that influences the fact he cannot return home.[82] These beings that are close to the gods include the Phaeacians who lived near the Cyclopes,[84] whose king, Alcinous, is the great-grandson of the king of the giants, Eurymedon, and the grandson of Poseidon.[82] Some of the other characters that Odysseus encounters are the cyclops Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon; Circe, a sorceress who turns men into animals; and the cannibalistic giants, the Laestrygonians.[82]

Guest-friendship

[edit]

Throughout the course of the epic, Odysseus encounters several examples of xenia ('guest-friendship'), which provide models of how hosts should and should not act.[85][86] The Phaeacians demonstrate exemplary guest-friendship by feeding Odysseus, giving him a place to sleep, and granting him many gifts and a safe voyage home, which are all things a good host should do. Polyphemus demonstrates poor guest-friendship. His only "gift" to Odysseus is that he will eat him last.[86] Calypso also exemplifies poor guest-friendship because she does not allow Odysseus to leave her island.[86] Another important factor to guest-friendship is that kingship implies generosity. It is assumed that a king has the means to be a generous host and is more generous with his own property.[86] This is best seen when Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, begs Antinous, one of the suitors, for food and Antinous denies his request. Odysseus essentially says that while Antinous may look like a king, he is far from a king since he is not generous.[87]

According to J. B. Hainsworth, guest-friendship follows a very specific pattern:[88]

- The arrival and the reception of the guest.

- Bathing or providing fresh clothes to the guest.

- Providing food and drink to the guest.

- Questions may be asked of the guest and entertainment should be provided by the host.

- The guest should be given a place to sleep, and both the guest and host retire for the night.

- The guest and host exchange gifts, the guest is granted a safe journey home, and the guest departs.

Another important factor of guest-friendship is not keeping the guest longer than they wish and also promising their safety while they are a guest within the host's home.[85][89]

Testing

[edit]

Another theme throughout the Odyssey is testing.[90] This occurs in two distinct ways. Odysseus tests the loyalty of others and others test Odysseus's identity. An example of Odysseus testing the loyalties of others is when he returns home.[90] Instead of immediately revealing his identity, he arrives disguised as a beggar and then proceeds to determine who in his house has remained loyal to him and who has helped the suitors. After Odysseus reveals his true identity, the characters test Odysseus's identity to see if he really is who he says he is.[90] For instance, Penelope tests Odysseus's identity by saying that she will move the bed into the other room for him. This is a difficult task since it is made out of a living tree that would require being cut down, a fact that only the real Odysseus would know, thus proving his identity.[90]

Testing also has a very specific type scene that accompanies it. Throughout the epic, the testing of others follows a typical pattern. This pattern is:[90][89]

- Odysseus is hesitant to question the loyalties of others.

- Odysseus tests the loyalties of others by questioning them.

- The characters reply to Odysseus's questions.

- Odysseus proceeds to reveal his identity.

- The characters test Odysseus's identity.

- There is a rise of emotions associated with Odysseus's recognition, usually lament or joy.

- Finally, the reconciled characters work together.

Omens

[edit]

Omens occur frequently throughout the Odyssey. Within the epic poem, they frequently involve birds.[91] According to Thornton, most crucial is who receives each omen and in what way it manifests. For instance, bird omens are shown to Telemachus, Penelope, Odysseus, and the suitors.[91] Telemachus and Penelope receive their omens as well in the form of words, sneezes, and dreams.[91] However, Odysseus is the only character who receives thunder or lightning as an omen.[92][93] She highlights this as crucial because lightning, as a symbol of Zeus, represents the kingship of Odysseus.[91] Odysseus is associated with Zeus throughout both the Iliad and the Odyssey.[94]

Omens are another example of a type scene in the Odyssey. Two important parts of an omen type scene are the recognition of the omen, followed by its interpretation.[91] In the Odyssey, all of the bird omens—with the exception of the first—show large birds attacking smaller birds.[91][89] Accompanying each omen is a wish which can be either explicitly stated or only implied.[91] For example, Telemachus wishes for vengeance[95] and for Odysseus to be home,[96] Penelope wishes for Odysseus's return,[97] and the suitors wish for the death of Telemachus.[98]

Reception

[edit]Pre-classical period to late antiquity

[edit]Homer was widely celebrated in Greek society as an impressively talented and didactic poet, instructing audiences on topics ranging from philosophy to science.[99] Audiences were primarily exposed to the epics through performances in both Archaic and Classical Greece,[100] but their status among audiences in the early Archaic period (840–700 BC) is not understood.[4] Scholars of at least two ancient libraries—the Library of Alexandria and the Library of Pergamum[h]—studied ancient versions of the Homeric epics.[19] Alexandrian scholars included Zenodotus of Ephesus (early third century BC), Aristophanes of Byzantium (early second century BC) and Aristarchus of Samothrace (mid-second century BC).[102]

Ancient scholarship explored a variety of topics. Some explored narrative inconsistencies,[103] for example. Allegory was a particularly common interpretation.[104] Wilson says this interpretation allowed scholars "to make sense of puzzling or disturbing scenes in the Odyssey".[105] Allegorical arguments also defended from Homer allegations that he had disrespected the gods[106][107]—a criticism famously made by the fifth/sixth-century BC philosopher Xenophanes[108]—but were rejected by Alexandrian scholars as too convenient.[107] Pergamon scholar Crates of Mallus explored the epics as containing allegorical insight into cosmology and geography.[101] Heraclitus (late sixth/early fifth century BC) and Porphyry (third century) also wrote allegorical interpretations.[109][110] Porphyry's Homeric Questions is the sole surviving large Homeric essay of the classical era. He limited his analytical scope to only explore questions that the Homeric text answered—he called this the Aristarchan principle.[111] Porphyry saw the nymphs' caves as representing human life,[104] and Heraclitis argued that Telemachus' encounter with Athena represented "the development of rationality" as he becomes a man.[104]

Many ancient editions of the Homeric epics existed; the Alexandrian library possessed some.[112] In material derived from the commentary of the fourth-century scholar Didymus, ancient versions were divided into "city editions" and "individual editions".[i] City editions were likely created within the city (perhaps as "official" versions) while individual editions were prepared independently by scholars.[114] He mentions individual versions owned by Antimachus, Aristophanes of Byzantium, Sosigenes,[114] Rhianus of Crete, Callistratus, and Philemon.[114] City editions are known in Argos, Chios, Crete, Cyprus, and Marseille.[114] Both the Iliad and the Odyssey were school texts in places where the Greek language was spoken.[115][116] They were probably part of the curriculum for the elite of Classical Athens,[117] and in the Roman Empire. They were regarded as instructive for rhetorical skill,[118][j] and reading.[k] The Trojan War and its participants were already important mythological and historical references for the Roman Empire,[120] and the they readily absorbed Homer into its culture, transmitting the epic east and west.[4]

Alexander the Great's conquests spread Hellenistic cultural influence throughout the Eastern Mediterranean; it became read by every school child in the Greek world.[121] By the sixth century, the Homeric poems had a canonical place within the institutions of ancient Athens.[122] The Athenian tyrant Peisistratos or his son Hipparchus instituted a civic and religious festival, the Panathenaia, which probably featured performances of Homeric poetry;[123][124][l] a "correct" version had to be performed, possibly indicating that a version of the text had become canonised.[3][m] They may only have performed sections of the poems,[125] and it is not likely that they were performed without a break.[126]

Post-classical

[edit]Beyond classical antiquity and into the Byzantine era, the spread of the Greek language—and the consequent internal translation of the Homeric texts as it spread—maintained the Odyssey's relevancy and status.[n] Armstrong says both epics may have dropped from knowledge otherwise, citing Beowulf as an example of this fate.[128] The orthodox Byzantine view was that Homer wrote the two epics alongside the Homeric Hymns and the Batrachomyomachia, with some philological scepticism over the latter.[129] The Iliad and the Odyssey remained widely studied throughout the Middle Ages and were used as school texts within the Byzantine Empire.[115][116] Homeric Greek was difficult for Byzantine students, requiring paratexts to explain grammatical and mythological references.[130] Much of the surviving Byzantine scholarship was originally intended as educational material.[131][o] Students probably did not have physical copies of the epics, but certain manuscripts might have been made available to talented students. They primarily learned via dictation and repetition.[134]

According to Lamberton, the audience of the epics changed in the middle Byzantine age. Once the domain of grammarians and students, adults began to read them for pleasure and wondered the narratives of the Iliad and the Odyssey related to the wider Trojan narrative.[135] The twelfth-century poet John Tzetzes produced Homeric Allegories for Manuel I Komnenos's consort, which summarised Odyssey and other texts.[135] Mavroudi says Tzetzes' work married cultural concepts from the Homeric and Byzantine periods; Tzetzes compared Manuel I to the kingly figures of Zeus and Agamemnon,[136] and depicted Odysseus with a protruding stomach.[137]

Byzantine interpretation was influenced by the Homeric Questions of Porphyry by way of Neopythagorean and Neoplatonic scholars.[138][139] The Byzantine scholar and archbishop Eustathios of Thessalonike (c. 1115 – c. 1195/6 AD) wrote exhaustive commentaries on both of the Homeric epics that were seen as authoritative by later generations;[115][116] his commentary on the Odyssey alone spans nearly 2,000 oversized pages in a twentieth-century edition.[115] The first printed edition of the Odyssey, or the editio princeps,[p] was produced in 1488 by the Greek scholar Demetrios Chalkokondyles, who was born in Athens and studied in Constantinople.[115][116] His edition was printed in Milan by a Greek printer named Antonios Damilas in Milan.[116]

Early modern

[edit]

During the quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns—a late 17th- and early 18th-century artistic debate in France—the Odyssey and Iliad were two of the primary subjects. The Homeric texts were criticised by the writers Jean Desmarets, Pierre Bayle, and Charles Perrault;[141] Howard Clarke says that Perrault refrained from directly castigating the poems in the absence of a French epic, with Perrault granting Homer "ritual praise" by describing him as "Father of all the Arts". Defenders of the epics and Homer included Jean de La Fontaine and Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux.[141] The debate subsided briefly in 1700, later reigniting between the French scholars Anne Dacier, a translator and staunch defender of Homer, and the Moderns proponent Antoine Houdar de la Motte.[142] Dacier's Homeric translations included a 90-page introduction addressing the criticisms of Perrault and other Moderns; in his abridged translation of Homer, Houdar de la Motte responded, and Dacier produced a 600-page rebuttal. A rhetorical ceasefire was called in 1716.[143]

As part of the quarrel, questions arose over the traditional view of Homer as a singular poet.[144] François Hédelin, Abbé d’ Aubignac criticised Homer's sustenance of theme; his language; and observed that nothing was known about his life.[145] Perrault posited that the epics were written by different poets, possibly from each city that claimed to be Homer's birthplace, and then assembled; he credited the theory to the late Hédelin.[146] Richard Bentley argued that the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus assembled different songs five-hundred years after initial composition.[147] His research also showed that Homeric Greek did not resemble the Greek of the classical period.[5]

Modern

[edit]In the early 20th century, Milman Parry and Albert Lord demonstrated that illiterate singers could exploit formulaic language to improvise large poems, much like the Homeric Greek.[14] Of the 27,803 lines in the original texts, around 9200 are repetitions, ranging from groups of words to entire sections.[148] Their research decisively showed that the Homeric texts formed as oral poetry.[149] Parry and Lord were investigating the South Slavic epic tradition, inspired by the work of philologist Matija Murko.[14] Parry's doctoral thesis had explored traditional Homeric epithets, drawing from the work of French linguist Antoine Meillet, but he did not comprehend the significance completely until travelling to Yugoslavia to conduct field work with Lord.[150][q] Scholarship became increasingly interdisciplinary in the late twentieth century, synthesising literary research with archaeological and religious findings.[63]

Legacy

[edit]

The influence of the Homeric texts can be difficult to summarise because of how greatly they have affected the popular imagination and cultural values.[152] The Odyssey and the Iliad formed the basis of education for members of ancient Mediterranean society. That curriculum was adopted by Western humanists,[153] meaning the text was so much a part of the cultural fabric that an individual having read it was irrelevant.[154] Robert Browning says that the scholarship Alexandrian library "laid the foundation" for "European literacy and philological studies".[107] The epics mark the beginning of the Western literary tradition and, according to Corinne Ondine Pasche, have unrivalled influence.[11] The Odyssey has reverberated over a millennium of writing; a poll of experts for BBC Culture named it literature's most enduring narrative.[155]

Translation

[edit]Livius Andronicus produced a Latin translation, Odusia.[156] Little is known about the full work, which was probably not simply a translation,[157] but surviving fragments are more formal than the original, and he reappropriated Homeric imagery from one part of the poem to another.[158] Livius' Odusia eventually became a school text for Latin students; Michael von Albrecht says his translation was "beaten into" a young Horace.[159] Nicholas Sigeros provided Petrarch with manuscripts of the Iliad and the Odyssey in 1354.[r] Petrarch's correspondent Giovanni Boccaccio persuaded a monk to called Pilato to produce translations in Latin prose—he finished the Iliad, but only came close to finishing the Odyssey.[160] The first printed edition in Greek was published in Milan 1488 by Demetrios Chalkokondyles, a Greek scholar resident in Florence.[161]

Printed translations for modern European languages surged in popularity in the 16th century,[162] although many were only partial translations.[163] The most popular edition of the century was a word-for-word Latin translation by Andreas Divus.[162] The first completed Italian Odyssey, written by Girolamo Baccelli in free verse, was published in 1582.[164] The first completed French translation was composed in Alexandrine couplets by Salomon Certon and printed in 1604.[163] It lost public favour following the Académie Française language reforms in the 1630s and 1640s.[165] Arthur Hall was the first to translate Homer into English: his translation of the Iliad's first 10 books, which was published in 1581,[164] relied upon a French version.[166] George Chapman became the first writer to complete a translation of both epics into English after finishing his translation of the Odyssey.[167] These translations were published together in 1616, but were serialised earlier, and became the first modern translations to enjoy widespread success.[168] He worked on Homeric translation for most of his life,[169] and his work later inspired John Keats' sonnet "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer" (1816).[170] Emily Wilson writes that almost all prominent translators of Greco-Roman literature had been men,[171] arguing this impacted the popular understanding of the Odyssey.[172][s]

Johann Heinrich Voss' 18th-century translations of the epics are among his most celebrated works,[174][t] and profoundly influenced the German language.[175] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe called Voss' translations transformational masterpieces that initiated interest German Hellenism.[176] Anne Dacier translated the Iliad and Odyssey into French prose,[u] appearing in 1711 and 1716, respectively;[165] it was the standard French Homeric translation until the late 18th century.[178] Antoine Houdar de La Motte, who could not read Greek, used Dacier's Iliad to produce his own contracted version of the Iliad and criticised Homer in the preface.[142][v] Dacier's translation of the Odyssey profoundly influenced the 1720s translation by Alexander Pope,[180][w] which he produced for financial reasons years after his Iliad.[181] He translated twelve books himself and divided the other twelve between Elijah Fenton and William Broome; the latter also provided annotations.[182][183] This information eventually leaked, harming his reputation and profits.[184] The first Odyssey in the Russian language may have been Vasily Zhukovsky's 1849 translation in hexameter.[185][186] Luo Niansheng began translating the first Chinese language Iliad in the late 1980s, but he died in 1990 before completing it; his student Wang Huansheng finished the project, which was published in 1994. Huansheng's Odyssey followed three years later.[187]

Literature

[edit]Classicist Edith Hall says the Odyssey has been regarded as "the very birthplace of literary fiction"; in T. E. Lawrence's 1932 introduction to the epic, he called it "the greatest novel ever written".[188] It is widely regarded by western literary critics as a timeless classic,[189] and it remains one of the oldest pieces of literature regularly read by Western audiences.[190] Brian Stableford, who described it as a kind of forerunner to science fiction, says it has been reconfigured as science fiction more than any other literary work.[191]

In Canto XXVI of the Inferno, Dante Alighieri meets Odysseus in the eighth circle of hell: Odysseus appends a new ending to the epic in which he continues adventuring and does not return to Ithaca.[192] Edith Hall suggests that Dante's depiction of Odysseus became understood as a manifestation of Renaissance colonialism and othering, with the cyclops standing in for "accounts of monstrous races on the edge of the world", and his defeat as symbolising "the Roman domination of the western Mediterranean".[85] Some of Odysseus's adventures reappear in the Arabic tales of Sinbad the Sailor.[193][194]

The Irish writer James Joyce's modernist novel Ulysses (1922) was significantly influenced by the Odyssey. Joyce had encountered the figure of Odysseus in Charles Lamb's Adventures of Ulysses, an adaptation of the epic poem for children, which seems to have established the Latin name in Joyce's mind.[195][196] Ulysses, a re-telling of the Odyssey set in Dublin, is divided into eighteen sections ("episodes") which can be mapped roughly onto the twenty-four books of the Odyssey.[197] Joyce claimed familiarity with the original Homeric Greek, but this has been disputed by some scholars, who cite his poor grasp of the language as evidence to the contrary.[198] The book, and especially its stream of consciousness prose, is widely considered foundational to the modernist genre.[199]

Modern writers have revisited the Odyssey to highlight the poem's female characters. Canadian writer Margaret Atwood adapted parts of the Odyssey for her novella The Penelopiad (2005). The novella focuses on Penelope and the twelve female slaves hanged by Odysseus at the poem's ending,[200] an image which haunted Atwood.[201] Atwood's novella comments on the original text, wherein Odysseus's successful return to Ithaca symbolises the restoration of a patriarchal system.[201] Similarly, Madeline Miller's Circe (2018) revisits the relationship between Odysseus and Circe on Aeaea.[202] As a reader, Miller was frustrated by Circe's lack of motivation in the original poem and sought to explain her capriciousness.[203] The novel recontextualises the sorceress' transformations of sailors into pigs from an act of malice into one of self-defence, given that she has no superhuman strength with which to repel attackers.[204]

Film and television

[edit]- L'Odissea (1911) is an Italian silent film by Giuseppe de Liguoro.[205]

- Ulysses (1954) is an Italian film adaptation starring Kirk Douglas as Ulysses, Silvana Mangano as Penelope and Circe, and Anthony Quinn as Antinous.[206]

- L'Odissea (1968) is an Italian-French-German-Yugoslavian television miniseries praised for its faithful rendering of the original epic.[207]

- Ulysses 31 (1981–1982) is a French-Japanese television animated series set in the futuristic 31st century.[208]

- Nostos: The Return (1989) is an Italian film about Odysseus's homecoming. Directed by Franco Piavoli, it relies on visual storytelling and has a strong focus on nature.[209]

- Ulysses' Gaze (1995), directed by Theo Angelopoulos, has many of the elements of the Odyssey set against the backdrop of the most recent and previous Balkan Wars.[210]

- The Odyssey (1997) is a television miniseries directed by Andrei Konchalovsky and starring Armand Assante as Odysseus and Greta Scacchi as Penelope.[211]

- O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) is a crime comedy drama film written, produced, co-edited and directed by the Coen brothers and is very loosely based on Homer's poem.[212]

- The Return (2024) is a film based on Books 13–24, directed by Uberto Pasolini and starring Ralph Fiennes as Odysseus and Juliette Binoche as Penelope.[213]

- The Odyssey (2026), written and directed by Christopher Nolan, will be based on the books and is slated to be released in 2026.[214]

Opera and music

[edit]- Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, first performed in 1640, is an opera by Claudio Monteverdi based on the second half of Homer's Odyssey.[215]

- Rolf Riehm composed an opera based on the myth, Sirenen – Bilder des Begehrens und des Vernichtens (Sirens – Images of Desire and Destruction), which premiered at the Oper Frankfurt in 2014.[216]

- Robert W. Smith's second symphony for concert band, The Odyssey, tells four of the main highlights of the story in the piece's four movements: "The Iliad", "The Winds of Poseidon", "The Isle of Calypso", and "Ithaca".[217]

- Jean-Claude Gallota's ballet Ulysse,[218] based on the Odyssey, but also on the work by James Joyce, Ulysses.[219]

- Jorge Rivera-Herrans' sung-through work Epic: The Musical tells the story of the Odyssey over the course of nine "sagas", beginning with the end of the Trojan War and carrying through to Odysseus's homecoming to Ithaca.[220][221]

Sciences

[edit]- Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay wrote two books, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character (1994)[222] and Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming (2002),[223] which relate the Iliad and the Odyssey to posttraumatic stress disorder and moral injury as seen in the rehabilitation histories of combat veteran patients.

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Inscribed on a clay cup found in Ischia, Italy, are the words "Nestor's cup, good to drink from".[7]. Some scholars, such as Calvert Watkins, have tied this cup to a description of King Nestor's golden cup in the Iliad.[8] If the cup is an allusion to the Iliad, that poem's composition can be dated to at least 700–750 BC.[3]

- ^ Papyri containing fragments of the Odyssey have been discovered in Egypt, preserved by the dry climate; these date to the 3rd century BC and differ from medieval versions.[10]

- ^ These include the pairing of nouns with adjectival epithets; type scenes, and chiastic structure.[13]

- ^ Calling these parts 'books' is anachronistic.[26]

- ^ The Ionic alphabet ranged from 20 to 26 letters during the Homeric period.[28]

- ^ This observation is known as "Monro's law" after David Monro.[38]

- ^ During the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, the Moderns found long Homeric similes so displeasing that they named them comparisons à longue queuë ("long-tailed similes").[68]

- ^ These libraries were rivals in the early second century BC. Alexandria saw an scholarly exodus due to internal political disagreements. The Roman Republic took control of the Pergamon in 133 BC.[101]

- ^ City editions were variously called ekdoseis kata, poleis, apo tōn poleōn, or apo tōn poleōn, or politikai; individual editions were ekdoseis kat’andra.[113]

- ^ Homer was repeatedly called "the father of oratory" throughout antiquity, including by Telephus of Pergamum.[119]

- ^ Robert Browning writes: "It may seem odd today that children should be taught the art of reading from poems composed in a form of language which no one actually spoke or ever had spoken, but Greek society was not the only one that taught them this way."[107]

- ^ Marry Ebbott writes: "Ancient sources indicate that rhapsodes performed in 'musical contests' (mousikoi agōnes) at the Panathenaia from at least the late sixth century through the late fourth century BC".[125]

- ^ According to Mary Ebbott, rhapsodes played selections from the Iliad and the Odyssey, which slowly contributed to Athenians identifying only those poems as Homer's work.[125]

- ^ Some scholars have argued that religious tension in this period was caused by the spread of Christianity because Homer was increasingly identified as pagan, but there is no academic consensus.[127]

- ^ We have one surviving work from an anonymous Byzantine scholar (published as Homeric Epirisms in 1983), probably from the mid-9th century.[132][133]

- ^ The Odyssey was not the only text in this edition: it included all works classically attributed to Homer: the Illiad, the Batrachomyomachia, and the Homeric Hymns.[140] Maria Mavroudi attributes Demetrios' assemblage of all prospective Homeric texts for his editon to the interest of Byzantine scholars in interpreting the texts over debating their authorship.[129]

- ^ Parry died, aged 33, from an accidental gunshot wound to the chest.[151]

- ^ Petrarch wrote in a letter: "Homer is mute to me, or, rather, I am deaf to him. Still, I enjoy just looking at him and often, embracing him and sighing, I say, 'O great man, how eagerly would

- ^ Wilson argues these inflected the narrative with connotations not present in the original text. For example, she says several translators interpreted the language used to refer to the slaves having sex with the suitors—the femine article hai (lit. 'those female people')—as meaning sluts or whores.[173]

- ^ Voss produced translations of other classics, too, and eventually revised his version of Odyssey, but that received a less favourable reception.[174]

- ^ Dacier's Iliad was critically well received; she provided historical and lingusitic commentary alongside it.[177]

- ^ Houdar de la Motte's translation was much shorter and modernised. His argument that he had improved upon Homer angered Dacier, who penned a 600-page rebuttal.[179]

- ^ Dacier did not speak English and, to read Pope's Odyssey, relied upon a poor translation of it; she condemned it in a prefatory note a new version of her Iliad. Pope admired Dacier and was hurt, but she died in 1720 before he could respond.[178]

References

[edit]- ^ Cambridge Dictionary 2025.

- ^ Ὀδύσσεια. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.Harper, Douglas. "odyssey". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson 2018, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Lamberton 2020, p. 411.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson 2020, p. xiii.

- ^ Wilson 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Higgins 2019.

- ^ Watkins 1976, p. 28.

- ^ Pfeiffer 1968, p. 25.

- ^ Daley 2018.

- ^ a b Pache 2020, p. xxvii.

- ^ a b Wilson 2020, p. xiv–xv.

- ^ Dué & Marks 2020, p. 588.

- ^ a b c Hall 2008, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Finkelberg 2003, p. 68.

- ^ a b Dué & Marks 2020, p. 585.

- ^ Nagy 2020, p. 82.

- ^ a b Nagy 2020, p. 81.

- ^ a b Nagy 2020, p. 92.

- ^ Myrsiades & Pinsker 1976, p. 237.

- ^ Foley 2002, p. 82.

- ^ Ebbott 2020, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Ebbott 2020, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Ebbott 2020, p. 12.

- ^ Martin 2020, p. 38.

- ^ a b Muellner 2020, p. 24.

- ^ González 2020, p. 140.

- ^ Taplin 1995, p. 285.

- ^ Lattimore 1951, p. 14.

- ^ Frame 2009, p. 561.

- ^ Jensen 1999, p. 5–90.

- ^ Jankos 2000.

- ^ Jensen 1999, p. 5–34.

- ^ Frame 2009, pp. 561–562.

- ^ Marks 2020, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Marks 2020, p. 51.

- ^ Monro 1901, p. 325.

- ^ Marks 2020, p. 50.

- ^ West 1997, p. 403.

- ^ West 1997, pp. 402–417.

- ^ West 1997, p. 405.

- ^ West 1997, p. 406.

- ^ West 1997, p. 410.

- ^ West 1997, p. 417.

- ^ a b Anderson 2000, p. 127.

- ^ Mayor 2000, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 123.

- ^ Stanford 1968, p. 8.

- ^ a b Fox 2008.

- ^ a b Strabo, Geographica, 1.2.15, cited in Finley 1976, p. 33

- ^ Zazzera 2019.

- ^ Jones 1996, p. xi.

- ^ a b Pache et al. 2020, pp. 275.

- ^ Foley 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Willcock 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Most 1989, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Cairns 2014, p. 231.

- ^ Carne-Ross 1998, p. lxi.

- ^ Jones 1996, p. 48.

- ^ Wilson 2020, p. lv.

- ^ Myrsiades 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Haslam 1976, p. 203.

- ^ a b Bremer, de Jong & Kalff 1987, p. vii.

- ^ Beck 2020, p. 203.

- ^ de Jong 2001, p. viii.

- ^ Clarke 1967, p. 102.

- ^ Wilson 2020, p. ix.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 126.

- ^ Karanika 2020, p. 201.

- ^ de Jong 2001, p. xviii.

- ^ de Jong 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Hardwick 2025, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Karanika 2020, p. 202.

- ^ Clarke 1967, p. 103.

- ^ Bonifazi 2009, pp. 481, 492.

- ^ Hall 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Bonifazi 2009, p. 481.

- ^ Thornton 1970, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Thornton 1970, pp. 1–15.

- ^ Thornton 1970, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Thornton 1970, pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c d e Thornton 1970, pp. 16–37.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 8.566.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 6.4–5.

- ^ a b c Reece 1993, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Thornton 1970, pp. 38–46.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 17.415–444.

- ^ Hainsworth 1972, pp. 320–321.

- ^ a b c Edwards 1992, pp. 284–330.

- ^ a b c d e Thornton 1970, pp. 47–51.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thornton 1970, pp. 52–57.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 20.103–104.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 21.414.

- ^ Kundmueller 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 2.143–145.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 15.155–159.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 19.136.

- ^ Lattimore 1975, 20.240–243.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 417.

- ^ Dué 2020, p. 6.

- ^ a b Kim 2020, p. 429.

- ^ Marks 2020, p. 92.

- ^ Wilson 2020, p. 315.

- ^ a b c Wilson 2020, p. 326.

- ^ Wilson 2020, p. Ixii.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Browning 1992, p. 134.

- ^ Christensen 2020a, p. 126.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 10.

- ^ Lamberton 1989, p. 114.

- ^ Lamberton 1989, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Schironi 2020, p. 114.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d Schironi 2020, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e Lamberton 2010, pp. 449–452.

- ^ a b c d e Browning 1992, pp. 134–148.

- ^ Kim 2020, pp. 411, 417.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 431.

- ^ Lamberton 1989, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Lamberton 2020, p. 417.

- ^ Pache et al. 2020, p. 417.

- ^ Davison 1955, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Davison 1955, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 420.

- ^ a b c Ebbott 2020, p. 13.

- ^ Fantuzzi & Tsagalis 2015a, p. 15.

- ^ Mavroudi 2020a, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Armstrong 2025, p. 6.

- ^ a b Mavroudi 2020a, p. 444.

- ^ Browning 1992, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Mavroudi 2020a, p. 446.

- ^ Dyck 1983, p. 7.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 137.

- ^ Browning 1992, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Browning 1992, p. 140.

- ^ Mavroudi 2020a, p. 447.

- ^ Stanford 1968, p. 254.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 135.

- ^ Lamberton 1989, p. 112.

- ^ Wolfe 2020, p. 491.

- ^ a b Clarke 1981, p. 122.

- ^ a b Clarke 1981, p. 123.

- ^ Candler Hayes 2025, p. 165.

- ^ Dué & Marks 2020, pp. 585–586.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 150.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 154.

- ^ Dué & Marks 2020, p. 587.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 264.

- ^ Thornton 1970, p. xi.

- ^ Dué & Nagy 2020, p. 590.

- ^ Wilson 2020, p. xv.

- ^ Kenner 1971, p. 50.

- ^ Hall 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Ruskin 1868, p. 17.

- ^ Haynes 2018.

- ^ Albrecht 1997, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Stanford 1968, p. 268.

- ^ Albrecht 1997, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Albrecht 1997, p. 117.

- ^ Clarke 1981, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 147.

- ^ a b Wolfe 2020, p. 495.

- ^ a b Wolfe 2020, p. 496.

- ^ a b Wolfe 2020, p. 497.

- ^ a b Candler Hayes 2025, p. 164.

- ^ Lawton 2020, p. 598.

- ^ Clarke 1981, p. 57.

- ^ Fay 1952, p. 104.

- ^ Brammall 2018.

- ^ Grafton, Most & Settis 2010, p. 331.

- ^ Wilson Guardian 2017.

- ^ Wilson 2018, p. 86.

- ^ Wilson 2017.

- ^ a b Curran 1996, pp. 173–175.

- ^ Steiner 1975, p. 266.

- ^ Steiner 1975, p. 259.

- ^ Candler Hayes 2025, p. 168.

- ^ a b Candler Hayes 2025, p. 176.

- ^ Candler Hayes 2025, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Armstrong 2018, p. 225.

- ^ Baines 2000, p. 25.

- ^ Gray 1984, p. 108.

- ^ Barnard 2003, p. 509.

- ^ Damrosch 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Cooper 2007, p. 196.

- ^ UOM 2012.

- ^ Zhang 2021, pp. 353–354.

- ^ Hall 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (15 March 2017). "Odyssey". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ North 2017.

- ^ Stableford 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Mayor 2000, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Sinbad the Sailor". Encyclopedia Brittanica. Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ^ Burton, Richard (1885). The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night Volume VI (PDF). The Burton Club; Oxford. p. 40.

- ^ Gorman 1939, p. 45.

- ^ Jaurretche 2005, p. 29.

- ^ Drabble, Margaret, ed. (1995). "Ulysses". The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1023. ISBN 978-0-19-866221-1.

- ^ Ames 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Williams, Linda R., ed. (1992). The Bloomsbury Guides to English Literature: The Twentieth Century. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 108–109.

- ^ Beard, Mary (28 October 2005). "Review: Helen of Troy | Weight | The Penelopiad | Songs on Bronze". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Margaret Atwood: A personal odyssey and how she rewrote Homer". The Independent. 28 October 2005. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Circe by Madeline Miller review – myth, magic and single motherhood". the Guardian. 21 April 2018. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020.

- ^ "'Circe' Gets A New Motivation". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018.

- ^ Messud, Claire (28 May 2018). "December's Book Club Pick: Turning Circe Into a Good Witch (Published 2018)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020.

- ^ Luzzi, Joseph (2020). Italian Cinema from the Silent Screen to the Digital Image. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441195616.

- ^ Wilson, Wendy S.; Herman, Gerald H. (2003). World History On The Screen: Film And Video Resources:grade 10–12. Walch Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8251-4615-2. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020.

- ^ Garcia Morcillo, Marta; Hanesworth, Pauline; Lapeña Marchena, Óscar (11 February 2015). Imagining Ancient Cities in Film: From Babylon to Cinecittà. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-135-01317-2.

- ^ "Ulysses 31 [Ulysse 31]". Our Mythical Childhood Survey. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Lapeña Marchena, Óscar (2018). "Ulysses in the Cinema: The Example of Nostos, il ritorno (Franco Piavoli, Italy, 1990)". In Rovira Guardiola, Rosario (ed.). The Ancient Mediterranean Sea in Modern Visual and Performing Arts: Sailing in Troubled Waters. Imagines – Classical Receptions in the Visual and Performing Arts. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4742-9859-9.

- ^ Grafton, Most & Settis 2010, p. 653.

- ^ Roman 2005, p. 267.

- ^ Siegel, Janice (2007). "The Coens' O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Homer's Odyssey". Mouseion: Journal of the Classical Association of Canada. 7 (3): 213–245. doi:10.1353/mou.0.0029. ISSN 1913-5416. S2CID 163006295. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020.

- ^ Ravindran, Manori (28 April 2023). "'English Patient' Stars Juliette Binoche, Ralph Fiennes Will Reunite in 'The Return,' a Gritty Take on 'The Odyssey'". Variety. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (23 December 2024). "Christopher Nolan's Next Film Is An Adaptation Of Homer's 'The Odyssey,' Universal Reveals". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 23 December 2024. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ "Monteverdi's 'The Return of Ulysses'". NPR. 23 March 2007. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017.

- ^ Griffel, Margaret Ross (2018). "Sirenen". Operas in German: A Dictionary. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-4422-4797-0. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "The Iliad (from The Odyssey (Symphony No. 2))". www.alfred.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020.

- ^ Entrée Ulysse, Philippe Le Moal, Dictionnaire de la danse (in French), éditions Larousse, 1999 ISBN 2035113180, p. 507.

- ^ Esiste uno stile Gallotta ? Archived 1 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine by Marinella Guatterini in 1994 on Romaeuropa's website (in Italian).

- ^ Rabinowitz, Chloe. "Epic: The Troy Saga Passes 3 Million Streams in First Week of Release". BroadwayWorld. Archived from the original on 13 November 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ McKinnon, Madeline. "Music Review: 'Epic: The Musical'". The Spectrum. Archived from the original on 9 November 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ Shay, Jonathan. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Scribner, 1994. ISBN 978-0-684-81321-9

- ^ Shay, Jonathan. Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming. New York: Scribner, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7432-1157-4

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Albrecht, Michael von (1997), A History of Roman Literature, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10711-3

- Anderson, Graham (2000). Fairytale in the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23702-4.

- Armstrong, Richard H.; Lianeri, Alexandra, eds. (2025). A Companion to the Translation of Classical Epic (1st ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9781119094265.

- Armstrong, Richard H. Introduction. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Candler Hayes, Julie. "Anne Dacier's Homer: Epic Force". In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Hardwick, Lorna. "Between Translation and Reception". In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Baines, Paul (2000). The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 0-203-16993-X. OCLC 48139753.

- Barnard, John (2003). Alexander Pope: The Critical Heritage. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-19423-2.

- Bremer, Jan Maarten; de Jong, Irene; Kalff, Jurriaan (1987). Homer: Beyond Oral Poetry. B.R. Grüner. ISBN 978-90-6032-215-4.

- Cairns, Douglas (2014). Defining Greek Narrative. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8010-8.

- Carne-Ross, D. S. (1998). "The Poem of Odysseus". The Odyssey. Translated by Fitzgerald, Robert. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-52574-3.

- Clarke, Howard W. (1967). "Appendix II: Translators and Translations". The Art of the Odyssey.

- Clarke, Howard W. (1981). Homer's Readers: A Historical Introduction to the Iliad and the Odyssey. University of Delaware Press.

- Damrosch, Leopold (1987). The imaginative world of Alexander Pope. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05975-7.

- de Jong, Irene J. F. (2001). A Narratological Commentary on the Odyssey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46478-9.

- Dyck, Andrew R., ed. (1983). Homeric Epirisms. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-006556-5.

- Fantuzzi, Marco; Tsagalis, Christos, eds. (2015). The Greek Epic Cycle and its Ancient Reception: A Companion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01259-2.

- Fantuzzi, Marco; Tsagalis, Christos (2015a). Introduction. In Fantuzzi & Tsagalis (2015).

- Finley, Moses (1976). The World of Odysseus (revised ed.). Viking Compass.

- Foley, John M. (2002). How to Read an Oral Poem. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07082-2.

- Fox, Robin Lane (2008). "Finding Neverland". Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Frame, Douglas (2009). Hippota Nestor. Center for Hellenic Studies.

- Gorman, Herbert Sherman (1939). James Joyce. Rinehart. OCLC 1035888158.

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010). The Classical Tradition. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- Gray, James (1984). ""Postscript to the "Odyssey"": Pope's Reluctant Debt to Milton". Milton Quarterly. 18 (4): 105–116. doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1984.tb00295.x. ISSN 0026-4326. JSTOR 24464409.

- Hall, Edith (2008). The Return of Ulysses: A Cultural History of Homer's Odyssey. I. B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 978-1-84511-575-3.

The two Homeric epics formed the basis of the education of every- one in ancient Mediterranean society from at least the seventh century BCE; that curriculum was in turn adopted by Western humanists

- Jaurretche, Colleen (2005). Beckett, Joyce and the art of the negative. European Joyce studies. Vol. 16. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1617-0.

- Jones, Peter V. (1996). Homer's Odyssey: A Companion to the English Translation of Richmond Lattimore. Classical studies series (Repr ed.). Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-85399-038-0.

- Kenner, Hugh (1971). The Pound Era. University of California Press.

- Lamberton, Robert (1989). Homer the Theologian: Neoplatonist Allegorical Reading and the Growth of the Epic Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06622-9.

- Lamberton, Robert; Keaney, John J., eds. (1992). Homer's Ancient Readers: The Hermeneutics of Greek Epic's Earliest Exegetes. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6916-5627-4.

- Browning, Robert. "The Byzantines and Homer". In Lamberton & Keaney (1992).

- Lamberton, Robert (2010). "Homer". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (eds.). The Classical Tradition. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- Lattimore, Richmond (1951). The Iliad of Homer. The University of Chicago Press.

- Lattimore, Richmond (1975). The Odyssey of Homer. Harper & Row.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2000). The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times. Princeton University Press.

- Monro, David (1901). Homer's Odyssey: Books XIII XXIV. Clarendon Press.

- Myrsiades, Kostas (2019). Reading Homer's Odyssey. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-68448-136-1.

- Pache, Corinne Ondine; Dué, Casey; Lupack, Susan; Lamberton, Robert, eds. (2020). The Cambridge Guide to Homer (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781139225649. ISBN 978-1-139-22564-9.

- Pache, Corinne Ondine. "General Introduction". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Dué, Casey. "Introduction (Part I)". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Martin, Richard P. "Homer in a World of Song". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Ebbott, Mary. "Homeric Epic in Performance". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Muellner, Leonard. "Homeric Poetics". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Marks, Jim. "Epic Traditions". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Nagy, Gregory. "From Song to Text". In Pache et al. (2020).

- González, José M. "Homer and the Alphabet". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Lamberton, Robert. "Introduction (Part III)". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Schironi, Francesca. "Early Editions". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Christensen, Joel P. (2020a). "Gods and Goddesses". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Karanika, Andromache. "Similes". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Beck, Deborah. "Speech". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Kim, Lawrence. "Homer in Antiquity". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Mavroudi, Maria (2020a). "Homer in Greece from the End of Antiquity: The Byzantine Reception of Homer and His Export to Other Cultures". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Wolfe, Jessica. "Homer in Renaissance Europe (1488–1649)". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Dué, Casey; Nagy, Gregory. "Milman Parry". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Dué, Casey; Marks, Jim. "Homeric Question". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Lawton, David. "Shakespeare and Homer". In Pache et al. (2020).

- Pfeiffer, Rudolf (1968). History of Classical Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the End of the Hellenistic Age. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814342-0.

- Reece, Steve (1993). The Stranger's Welcome: Oral Theory and the Aesthetics of the Homeric Hospitality Scene. University of Michigan Press.

- Roman, James W. (2005). From Daytime to Primetime: The History of American Television Programs. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31972-3.

- Ruskin, John (1868). The Mystery of Life and its Arts. Cambridge University Press.

- Stableford, Brian (2004) [1976]. "The Emergence of Science Fiction, 1516–1914". In Barron, Neil (ed.). Anatomy of Wonder: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction (5th ed.). Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-59158-171-0.

- Stanford, W. B. (1968). The Ulysses Theme: A Study in the Adaptability of the Traditional Hero (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press.

- Steiner, George (1975). After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. Oxford University Press.

- Taplin, Oliver (1995). Homeric Soundings: The Shaping of the Iliad (Revised ed.). Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815014-5.

- Thornton, Agathe (1970). People and Themes in Homer's Odyssey. Methuen.

- West, Martin (1997). The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. Clarendon Press.

- Willcock, Malcolm L. (2007). A Companion to The Iliad: Based on the Translation by Richard Lattimore. Phoenix Books. ISBN 978-0-226-89855-1.

- Wilson, Emily (2018). "Introduction: When Was The Odyssey Composed?". The Odyssey. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08905-9.

- Wilson, Emily (2020). The Odyssey: A Norton Critical Edition. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 9780393655063.

Journals, news and web

[edit]- Ames, Keri Elizabeth (2005). "Joyce's Aesthetic of the Double Negative and His Encounters with Homer's "Odyssey"". European Joyce Studies. 16: 15–48. ISSN 0923-9855. JSTOR 44871207. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Armstrong, Richard H. (2018). "Review of Homer: The Odyssey". Museum Helveticum. 75 (2): 225–226. ISSN 0027-4054. JSTOR 26831950.

- "Homer Odyssey: Oldest extract discovered on clay tablet". BBC News. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020.

- Bonifazi, Anna (Winter 2009). "Inquiring into Nostos and Its Cognates". The American Journal of Philology. 130 (4): 481–510. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 20616206.

- Brammall, Sheldon (1 July 2018). "Review: George Chapman: Homer's Iliad". Translation and Literature. 27 (2). doi:10.3366/tal.2018.0339. ISSN 0968-1361. S2CID 165293864.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Odyssey". Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. 2025. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021.

- Cooper, David L. (2007). "Vasilii Zhukovskii as a Translator and the Protean Russian Nation". The Russian Review. 66 (2). ISSN 0036-0341.

- Curran, Jane V. (1996). "Wieland's Revival of Horace". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 3 (2). ISSN 1073-0508.

- Daley, Jason (11 July 2018). "Oldest Greek Fragment of Homer Discovered on Clay Tablet". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Finkelberg, Margalit (2003). "Neoanalysis and Oral Tradition in Homeric Studies". Oral Tradition. 18 (1). doi:10.1353/ort.2004.0014. ISSN 1542-4308.

- Davison, J. A. (1955). "Peisistratus and Homer". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 86: 1–21. doi:10.2307/283605. ISSN 0065-9711. JSTOR 283605.

- Edwards, Mark W. (1992). "Homer and the Oral Tradition". Oral Tradition. 7 (2): 284–330.

- Fay, H. C. (1952). "George Chapman's Translation of Homer's 'iliad'". Greece & Rome. 21 (63): 104–111. doi:10.1017/S0017383500011578. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 640882. S2CID 161366016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Foley, John Miles (Spring 2007). ""Reading" Homer through Oral Tradition". College Literature. 34 (2): 1–28. ISSN 0093-3139. JSTOR 25115419.

- Hainsworth, J. B. (December 1972). "The Odyssey – Agathe Thornton: People and Themes in Homer's Odyssey". The Classical Review. 22 (3): 320–321. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00996720. ISSN 0009-840X. S2CID 163047986.

- Haslam, M. W. (1976). "Homeric Words and Homeric Metre: Two Doublets Examined (λείβω/εϊβω, γαΐα/αία)". Glotta. 54 (3/4): 201–211. ISSN 0017-1298. JSTOR 40266365.

- Haynes, Natalie (22 May 2018). "The Greatest Tale Ever Told?". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020.

- Higgins, Charlotte (13 November 2019). "From Carnage to a Camp Beauty Contest: The Endless Allure of Troy". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020.

- Jankos, Richard (2000). "Review: 'Dividing Homer: When and How were the Iliad and the Odyssey divided into songs?'". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. ISSN 1055-7660.

- Jensen, Minne Skafte (1999). "Dividing Homer: When and How were the Iliad and the Odyssey divided into songs?". Symbolae Osloenses. 74.

- Kundmueller, Michelle (2013). "Following Odysseus Home: an Exploration of the Politics of Honor and Family in the Iliad, Odyssey, and Plato's Republic". American Political Science: 1–39. SSRN 2301247.

- Liney, Nicolas (6 June 2020). "The Last Words of Milman Parry". The Oxonian Review. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020.

- Most, Glenn W. (1989). "The Structure and Function of Odysseus' Apologoi". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 119: 15–30. doi:10.2307/284257. ISSN 0360-5949. JSTOR 284257.

- Myrsiades, Kostas; Pinsker, Sanford (1976). "A Bibliographical Guide to Teaching the Homeric Epics in College Courses". College Literature. 3 (3): 237–259. ISSN 0093-3139. JSTOR 25111144. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- North, Anna (20 November 2017). "Historically, men translated the Odyssey. Here's what happened when a woman took the job". Vox. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Tagaris, Karolina (10 July 2018). Heavens, Andrew (ed.). "'Oldest known extract' of Homer's Odyssey discovered in Greece". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019.

- "The Wanderings of a Translation: From Greek to German to Russian". Translation at Michigan. University of Michigan. 30 September 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- Watkins, Calvert (1976). "Observations on the "Nestor's Cup" Inscription". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 80: 25–40. doi:10.2307/311231. ISSN 0073-0688. JSTOR 311231.

- Wilson, Emily (7 July 2017). "Found in Translation: How Women are Making the Classics Their Own". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020.

- Wilson, Emily (8 December 2017). "A Translator's Reckoning With the Women of The Odyssey". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Zazzera, Elizabeth Della (27 February 2019). "The Geography of the Odyssey". Lapham's Quarterly. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Zhang, Wei (2021). "Reading Homer in Contemporary China (From the 1980s Until Today)". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 28 (3). doi:10.2307/48698763. ISSN 1073-0508.

Further reading

[edit]- The Authoress of the Odyssey by Samuel Butler

- Austin, N. 1975. Archery at the Dark of the Moon: Poetic Problems in Homer's Odyssey. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Clayton, B. 2004. A Penelopean Poetics: Reweaving the Feminine in Homer's Odyssey. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- — 2011. "Polyphemus and Odysseus in the Nursery: Mother's Milk in the Cyclopeia." Arethusa 44(3):255–77.

- Bakker, E. J. 2013. The Meaning of Meat and the Structure of the Odyssey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barnouw, J. 2004. Odysseus, Hero of Practical Intelligence. Deliberation and Signs in Homer's Odyssey. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Dougherty, C. 2001. The Raft of Odysseus: The Ethnographic Imagination of Homer's Odyssey. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fenik, B. 1974. Studies in the Odyssey. Hermes: Einzelschriften 30. Wiesbaden, West Germany: F. Steiner.

- Griffin, J. 1987. Homer: The Odyssey. Landmarks in World Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Louden, B. 2011. Homer's Odyssey and the Near East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- — 1999. The Odyssey: Structure, Narration and Meaning. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Li, Sher-shiueh (4 May 2014). ""Translating" Homer and his epics in late imperial China: Christian missionaries' perspectives". Asia Pacific Translation and Intercultural Studies. 1 (2): 83–106. doi:10.1080/23306343.2014.883750. ISSN 2330-6343.

- Müller, W. G. 2015. "From Homer's Odyssey to Joyce's Ulysses: Theory and Practice of an Ethical Narratology." Arcadia 50(1):9–36.

- Perpinyà, Núria. 2008. Las criptas de la crítica. Veinte lecturas de la Odisea [The Crypts of Criticism: Twenty Interpretations of the 'Odyssey']. Madrid: Gredos. Lay summary Archived 18 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine via El Cultural (in Spanish).

- Reece, Steve. 2011. "Toward an Ethnopoetically Grounded Edition of Homer's Odyssey Archived 1 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine." Oral Tradition 26:299–326.

- Saïd, S. 2011 [1998].. Homer and the Odyssey. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Thurman, Judith, "Mother Tongue: Emily Wilson makes Homer modern", The New Yorker, 18 September 2023, pp. 46–53. A biography, and presentation of the translation theories and practices, of Emily Wilson. "'As a translator, I was determined to make the whole human experience of the poems accessible,' Wilson said." (p. 47.)

External links

[edit]The Odyssey in ancient Greek

[edit]- The Odyssey (in Ancient Greek) on Perseus Project

- Odyssey: the Greek text presented with the translation by Butler and vocabulary, notes, and analysis of difficult grammatical forms

English translations

[edit]- The Odyssey, translated by William Cullen Bryant at Standard Ebooks

- The Odysseys of Homer, together with the shorter poems by Homer, trans. by George Chapman at Project Gutenberg

- The Odyssey, trans. by Alexander Pope at Project Gutenberg

- The Odyssey, trans. by William Cowper at Project Gutenberg

- The Odyssey, trans. by Samuel H. Butcher and Andrew Lang at Project Gutenberg

- The Odyssey, trans. by Samuel Butler at Project Gutenberg

- The Odyssey, trans. by A. T. Murray (1919) on Perseus Project

- Odyssey, trans. by Ian C. Johnston (2002; released into the public domain January 2024)

Other resources

[edit] The Odyssey public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Odyssey public domain audiobook at LibriVox- BBC audio file — In our time BBC Radio 4 [discussion programme, 45 mins]

- The Odyssey Comix — A detailed retelling and explanation of Homer's Odyssey in comic-strip format by Greek Myth Comix

- The Odyssey — Annotated text and analyses aligned to Common Core Standards

- "Homer's Odyssey: A Commentary" by Denton Jaques Snider on Project Gutenberg