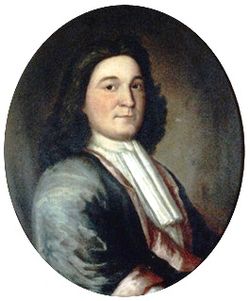

William Phips | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office May 16, 1692 – November 17, 1694 | |

| Monarchs | William III and Mary II |

| Lieutenant | William Stoughton |

| Preceded by | Simon Bradstreet (as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony) |

| Succeeded by | William Stoughton (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 2, 1650/51 Nequasset (Woolwich, Maine) |

| Died | February 18, 1694/95 (aged 44) London, Kingdom of England |

| Spouse | Mary Spencer Hull (married 1673) |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | The New England Knight |

Sir William Phips (or Phipps; February 2, 1651 – February 18, 1695)[Note 1] was the first royally appointed governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and the first native-born person from New England to be knighted. Phips was famous in his lifetime for recovering a large treasure from a sunken Spanish galleon but is perhaps best remembered today for establishing the court associated with the infamous Salem Witch Trials, which he grew unhappy with and was forced to prematurely disband after five months.

Early life

[edit]

Phips was born the son of James and Mary Phips in a frontier settlement at Nequasset (present-day Woolwich, Maine), near the mouth of the Kennebec River,[1] on February 2, 1651.[2] His father died when the boy was six years old, and his mother married a neighbor and business partner, John White.[1] Although Cotton Mather in his biography of Phips claimed that he was one of 26 children, this number is likely an exaggeration or includes many who did not survive infancy. His mother is known to have had six children by James Phips and eight by White.[3] His father was poor, but his ancestry may have descended from country gentry in Nottinghamshire, at least technically. Constantine Phipps, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, seems to have been a cousin of Phips, five years his junior.[4]

Phips watched over his family's flock of sheep, according to Mather, until the age of 18, after which he began a four-year apprenticeship as a ship's carpenter. He received no formal schooling. Despite a keen intelligence, his literacy skills were likely rudimentary. Robert Calef wrote, "It will be generally acknowledged, that not withstanding the meanness of his parentage and education, he attained to be master of a Ship."[5] Once Phips achieved wealth and fame, he relied on a personal secretary and scribes for assistance, as was common for many figures of the time.[6]

After his apprenticeship ended in 1673, Phips traveled to Boston, where he continued to employ his shipmaking and carpentry skills.[7] About a year later, he married Mary Spencer Hull, widow to John Hull (unrelated to Massachusetts mintmaster John Hull).[8] Mary's father, Daniel Spencer, was a merchant and landowner with interests in Maine. Phips may have known Mary from an early age.[9] By all accounts, the couple exhibited "genuine affection" for one another, and there is no evidence Phips was unfaithful during his long absences from home.[10]

Phips established a shipyard on the Sheepscot River at Merrymeeting Bay in Maine in 1675 at the outbreak of King Philips War. The shipyard was successful, turning out a number of small boats[11] and building its first large merchant ship in 1676. As he was preparing for its maiden voyage in August 1676, planning to deliver a load of lumber to Boston, a band of Indians descended on the area during the Northeast Coast Campaign (1676).[12] Rather than take on his cargo, he took on board as many of the local settlers as he could. Although he was financially ruined (the Indians destroyed the shipyard and his intended cargo of masts and lumber), Phips was considered a hero among the colonists in Boston.[13]

In the early 1680s, Phips began to engage in a favorite colonial pastime of treasure hunting in the Bahamas. As captain of the Resolution,[14] he was seeking treasure from sunken Spanish ships near New Providence.[15] The expedition is not well documented but seems to have been profitable, returning shares worth £54 to certain low-level participants. New England mintmaster John Hull was one of Phips's investors.[16] Phips earned a widespread reputation for "continually finding sunken ships".[17]

The voyage of HMS Rose of Algeree

[edit]Narborough's treasure hunt

[edit]On May 2, 1683, the captain of the frigate HMS Falcon was sailing from England to the West Indies and beckoned the other officers to be present as he broke open his secret instructions. He learned that his mission was to aid in the hunt for a large treasure near Hispaniola. A sloop in convoy, HMS Bonetta (sometimes Bonito), was designated to do most of the searching, but Falcon would act as aid and protection. These instructions were from Sir John Narborough, a rear admiral and commissioner of the Royal Navy, who also had the ear of King Charles II.[18]

Around this same time, the thirty-two-year-old Phips had made his way to England, where he gained an audience with Narborough and Charles II. By any measure, this was a remarkable achievement for a poor New Englander like Phips, but it also seems clear that he must have been at the right place at the right time. His reputation for finding sunken ships may have preceded him, and he seems to have had demonstrable gains to show, as one letter writer mentions his "late successful returns." He possibly delivered the King's portion of these returns to Whitehall in person.[19] A plan was concocted, probably by Narborough, whereby Phips would be assigned as the commander of a 20-gun frigate, HMS Rose of Algiers, for a treasure hunt but given no other financial backing. He and his crew would be required to pay for all other expenses of the voyage, including food and diving equipment, and give a deposit of £100. Of the treasure they found, 35% would go to the King, and the rest would be divided among the otherwise unpaid crew. On July 13, 1683, the articles of agreement (see image) were signed by Phips and seven other crew members, in the presence of Narborough and Haddock.[20]

Delivering Randolph

[edit]Before Phips could set sail, he had another mission added to the manifest. Edward Randolph, "indefatigable foe of Puritans",[21][22] was serving Boston with a writ of quo warranto against the Charter of Massachusetts and searching for a frigate to be the muscle backing him:

It is essential that a frigate should be on the New England coast at such a time to second the quo warranto and hasten submission; ... a war vessel be present to awe them.[19][23]

Randolph hoped such a display would induce New England to submit to revisions of their charter from the Crown, rather than having it fully revoked. On August 3, 1683, Randolph wrote to Sir Leoline Jenkins, "I am now informed that the H.M.S. Rose is already fitted out for the Bahamas with orders to call at Boston for 2 or 3 weeks on the way."[24] Randolph indicates that time is of the essence, and he is willing to travel with Phips or forego the frigate idea and embark on a merchantman. Randolph, along with his brother Bernard, were given passage and cabins on HMS Rose.

John Knepp's Account

[edit]Just before the Rose set sail, things were complicated again when the Crown decided to place a minder on board named John Knepp "to look after the King's interest". Knepp seems to have been a purser.[25] In the English Navy, the purser acted as a sort of Company Store, providing sailors whiskey, tobacco and other desirables which could be purchased with credit against their wages collected through the captain. It was a lucrative post and required an investment to procure, hence it usually went to young Naval clerks and scions who could afford the capital outlay.[26] The purser was dependent on good relations with the captain, yet Knepp seems to have looked down on Phips and decided to be forward in introducing himself to the crew of HMS Rose while Phips was absent in London. The reception was rather less than friendly:

... then most of them began to curse the ship and wished she had been afire before they saw her and that they had better have hired a ship of merchants ...[27]

Everything known about the crew comes from a detailed journal of the trip to Boston kept by Knepp,[28] and he has rightly been called a "hostile observer",[29] but he was often ignorant of the complex nature of the voyage, as well as basic colonial politics. By the time the ship set sail the next day, Phips and Knepp were distinctly at odds, as Knepp records when asked for a cabin or berth and was told he would have to make do sleeping on a trunk. The articles of agreement testify to the trust that the King and Narborough placed in Phips, and the crew seemed willing to do as Phips commanded, but Knepp acted as if he was not beholden to Phips. Knepp's journal is addressed to Narborough (and Haddock), and presents Phips in a negative light.[26] Knepp excelled at taking coordinates and seemed trained in piloting, but did not exhibit a breadth of experience or knowledge of the rigging. Though he recorded every perceived misstep by Phips, his careful plotting of the journey also shows the great ability Phips possessed as a sailor, crossing the Atlantic in half the time of another ship that they meet and making first landfall at Cape Ann.[27]

Randolph arrived at Boston

[edit]On October 27, Increase Mather recorded his one and only diary entry for all of 1683: "Randolph arrived at Boston."[30] Phips quickly began to provide a show of force for Randolph by insisting other ships strike their colors and firing across their bows if they did not. Knepp claims that Narborough did not condone this, and many historians have followed his lead in treating Phips' activities in Boston harbor as arrogant showboating, but it seems clear from the letters of Randolph and Blathwayt[31][Note 2] that Phips had reason for his actions Phips cites personal instructions from the King, and indeed Charles II was known to have insisted on a salute to his flag.[32] As Phips created chaos Massachusetts government, he continued to pursue his original intention of gathering diving equipment and divers to take to the Bahamas. Phips later followed the same procedures of requiring ships to strike in the West Indies and with a new crew in Bermuda. Phips lack of experience in the Royal Navy would suggest he likely made mistakes and did not always go about this procedure in the best way. It must have been a strange and uncomfortable chore for someone whose loyalties were with Boston.[8][Note 3] Randolph was never one to withhold criticism, but he did not complain of Phips activities in Boston harbor that winter,[29] and Randolph even seems to have assisted Phips by searching a ship for him. But choosing a threatening posture showed Randolph's inability to understand the New England character, and it did not produce the effect Randolph intended. The magistrates voted to submit to the crown, but the deputies resisted. Phips and the Rose became a focal point for the resistance.[33]

Randolph's writ of quo warranto required a response from Massachusetts by the end of "Michaelmas term." Having not received a response, Randolph and his brother boarded a ship bound for England on December 14. A few days later, Phips began making preparations but was detained by problems with the Boston government and the ongoing search for victuals.[28] Phips finally sailed clear of the Boston Harbor on January 19, 1684[34] but unfortunately not before some of his crew could caused a small riot in Boston and perpetrate a despicable assault in Hull, according to Knepp.[35] Knepp was not on board, meaning he had effectively deserted according to the Articles, "though I should be almost undone by it" and so it became all the more important for Knepp to show Phips in a bad light.

Two days after Phips left the Boston area, Increase Mather gave a rousing speech to the deputies and freemen advising them not to submit to the Crown and to resist the quo warranto. One historian calls this Increase Mather's "first important entry into politics."[21] {Mather's "Remarkable Providences" was distributed this same month, with echoes to the New England government Increase Mather assembles in 1692.} It had been Phips' debut into colonial politics too, if clumsily and involuntarily. To what extent he was swayed by the arguments of Randolph as they crossed the Atlantic, it is hard to know, but Phips certainly behaved as a royalist in the meetings he had with Bradstreet and Stoughton, at least as recorded by Knepp. However, by 1688, Phips had crossed over to Increase Mather's side and begun to consistently oppose Randolph and the Dominion government he helped bring about

After leaving Boston, Phips searched the picked over wrecks in the Bahamas with limited success. Too many other treasure hunters had already gone before. When some of his crew became mutinous, he had them put off in Jamaica. On November 18, 1684, Phips was in Port Royal, Jamaica, the same time as Captain Stanley of the Bonetta.[36] Soon afterward, Phips visited the north coast of Hispaniola and slowly cruised north exploring the banks where Stanley had been diligently searching for over a year.

After Phips returned to London in August 1685, Samuel Pepys ordered the Navy Board to assess the Rose. Pepys had been out of power when Narborough set the strange plan in motion. In March and May 1686, Phips was ordered to attend the Lord Treasurer, where it was found that the king was only to receive £471 in treasure, though the wear and tear on the Rose was estimated at £700.[37] In this age of piracy and high mortality, Phips making it back to London alive and with the King's ship still afloat was probably enough for him to pass the test. Already Narborough had a new plan in the works for Captain Phips, though this time it would be a private venture. Narborough's long infatuation with the Hispaniola treasure had not been diminished by Captain Stanley's discouragement on the Bonetta. Knepp's report on Phips did succeed in disqualifying Phips who had shown that he was serviceable: willing serve the interests of the Crown.

Finding Treasure

[edit]As Captain Stanley of the Bonetta expressed disinterest in continuing to search for the Hispaniola treasure, the next logical choice for commander was obvious. Narborough turned to the Duke of Albemarle who assembled a group of private investors to fund another expedition. Phips was tasked with finding suitable ships and these came to be the James and Mary, a 22-gun 200-ton frigate, and the 45-ton Henry of London, a sloop commanded by Francis Rogers,[38] Phips' second mate on the previous voyage (he had left the Rose in Boston ISTG Vol 4 - Salee Rose). Phips utilized experience as a sailor and shipwright to select high quality anchors, chains, and cables to hold their ships securely in close proximity to the shoals for months as they tried to fish treasure from it. £500 worth of merchandize was taken along to barter for provisions, as well as to provide cover, or a ruse, that they were in Hispaniola merely as merchants, not treasure hunters. The London investors must have felt confident because they paid a total of £3,210 outfitting the ships for the voyage.[39] Unlike the voyage of the Rose, the crew were to be paid regular wages.

Phips sailed from the Downs on September 12, 1686, and on November 28, arrived in Hispaniola, Samana Bay, where they spent two weeks restocking their water and provender. The weather was bad, and the search consequently did not get underway for a few more weeks. On January 12, Phips sent out Captain Rogers in the smaller Henry of London along with three Native American divers (including Jonas Abimeleck and John Pasqua; the name of the other diver is not listed) to search what was then called the Ambrosia Bank (now the Silver Bank). There was a bit more delay due to the weather, but Peter Earle writes, "There is no doubt that he knew exactly where he was going." On January 20, they spotted cannons from a shipwreck lying on the white sands of the reef. The ship they had found was the Almiranta of the Spanish silver fleet (later determined to be Nuestra Señora de la Concepción; the English did not know the name of the ship) wrecked in 1641.[40] Over the next two days, the divers were able to bring up 3,000 coins and 3 silver bars. They decided to travel back to Phips to let him know, but this turned out to be a somewhat slow and treacherous trip among the reefs. After Phips was discreetly informed of their amazing find, he spent the next nine days preparing the ships and gathering enough food to sustain the men over months of bringing up treasure.[41]

Through March and April, the divers and ships' crews worked to recover all manner of treasure: silver coins, silver bullion, doubloons, jewelry, a small amount of gold, and other artifacts. Concerned about the possibility of mutiny, Phips guaranteed to the crew, who had been hired for seaman's wages, that they would receive shares in the find even if he had to pay them from his own percentage.[42] He carefully avoided putting in at any ports before anchoring at Gravesend, where he dispatched a courier to London with the news.

The treasure weighed in at over 34 tons, or £205,536. Almost a quarter went to Albemarle.[43] Phips, after paying out £8,000 in crew shares, received £11,000.[44] Phips was treated as a hero in London, and the find was the talk of the town.[45] Some economic historians argue that Phips' find significantly affected history, because it led to a major increase in the formation of joint-stock companies and even played a role in the eventual formation of the Bank of England.[44]

Phips and the crew were rewarded by the investors with medals, and Phips was knighted by James in June. James also rewarded Phips with the post of Provost Marshal General (Chief Sheriff) of the Dominion of New England, serving under Sir Edmund Andros.[46] In September 1687, Phips returned to the wreck, though he did not command the venture. Admiral Narborough elected to personally lead the expedition, but it was not nearly as successful. The wreck had been discovered by others, and the arrival of the English scattered more than 20 smaller ships. Treasure worth £10,000 was recovered before Narborough's death in May 1688 brought the expedition to an end. Phips had by then already left the wreck site in early May, sailing for Boston for what seems to have been his first time home in four and a half years, to take up his new post as Provost Marshal General.[47]

Provost Marshal General

[edit]Phips arrived back in Boston in the summer of 1688 and was welcomed back as a hero. His wife seemed very happy to see him.[16] He was celebrated in sermons and at the Harvard College commencement he was compared to Jason fetching the Golden Fleece.[16] Andros and Randolph were not so happy to see him, and it seems the feeling was mutual. Almost all of New England was unified in their opposition to Andros and Randolph. Phips, despite having been Captain of Randolph's gunship in 1683-4, does not seem to have carried an association with Randolph in the minds of the people of Massachusetts Bay.

Andros swore Phips into his new post in early July, but his council refused Phips' demand that the previously named sheriffs be dismissed. Phips stayed in Boston only six weeks before travelling back to London to join with Increase Mather in opposing the Dominion and seeking to restore the original charter. This seems to be the first mention of Phips in Increase Mather's diary or correspondence.[21] Motivated by a shared dislike of Andros, Phips and Increase Mather worked together to bring about his downfall. After the Glorious Revolution in late 1688 replaced the Catholic James with the Protestant monarchs William III and Mary II, Phips and Mather petitioned the new monarchs for restoration of the Massachusetts charter[48] and successfully convinced the Lords of Trade to delay the transmission of formal instructions about the change of power to Andros. Phips returned to Boston in May 1689, carrying proclamations from the King and Queen and found Andros and Randolph had already been arrested in a revolt in Boston.[49] Phips served for a time as an Overseer guarding Andros and Randolph in the prison at Castle Island.[50]

Entry into Politics

[edit]If Paris were worth a mass to Henry IV, Boston was worth a conversion, in the Puritan sense, to William Phips.[51]

The turmoil in England and William's accession to the throne had prompted New France's Governor to take advantage of the political turmoil in New England, launching a series of Indian raids across the northern frontier in 1689 and early 1690.[52] When a frontier town in Maine was overrun in early March 1690, the French were perceived as instigators and the provisional government of Massachusetts began casting about for a major general to lead an expedition against the French in Acadia. Phips had not demonstrated military interests as a young man. During King Philip's War, when many took up arms, Phips built ships and cut lumber. John Knepp's journal testifies to Phips' constitutional disinterest in military discipline.[27] Yet Phips' control of a naval gunship, and his subsequent actions, seem to have suggested he was a good candidate to lead a large military expedition. Sewall writes:

Saturday, March 22. Sir William Phips offers himself to go in person, the Governor [Bradstreet] sends for me, and tells me of it, I tell the [General] Court; they send for Sir William who accepts to go, and is appointed to command the forces. Major Townsend relinquishes with thanks. Sir William had been sent to at first; but some feared he would not go; others thought his Lady would not consent. Court makes Sir William free and swear him Major General, and several others. Adjourn to Boston, Wednesday,14 night one o'clock.[16]

This is Sewall's entire entry, and he has no entry for the next day. It shows that Phips, though knighted, one of the richest men in the colony, and highly active on the colony's behalf, was not yet able to vote or serve under the provisional government because they were following the old charter, wherein only church members were free. The court, not the church, made Phips free on this Saturday, according to Sewall. Sewall was religiously devout and active in his church congregation and would not likely have misspoken or deliberately withheld information on this point. Sewall's diary is generally considered trustworthy and is widely referenced by historians.

Some years later, after Phips' death, Cotton Mather anonymously wrote a biography of Phips and sent it away to London for publication although he could have done so in Boston.[53] He implausibly cast this scenario as a spontaneous spiritual awakening, including heartfelt testimony, which Cotton Mather claims to faithfully transcribe "without adding so much as one word unto it."[54]

Both events are not mutually exclusive. Cotton Mather places the baptism the next day, March 23. The general court in which Cotton Mather played an active role may have made Phips free with the understanding that Cotton Mather would add him to the rolls of the North Church. Records of the North Church show Phips' name added to admissions. (Curiously, a "B" for "brother" is withheld as prefix to his name, unlike all others. See image.) Another book, mostly recording infant baptisms, lists Phips as "Admitted and Baptized." Phip's wife's name does not seems not to appear in the records at all. The admission and baptism of an adult was generally a somewhat drawn-out process over some weeks.[55] There seems to be no surviving record of Phips "coming to the table" to partake in the Lord's Supper, as only church members were invited to do.

The only other reference to a baptism of Phips is not first-hand but a sardonic reference by Blathwayt (Randolph's boss in London) mentioning Phips being made a general the same year he was "publicly christened at Boston."[56] Expanding the franchise of New England away from the control of the clergy was one of Blathwayt's obsessions, and his comment probably goes to this point, as well as noting Phips loyalty with New England as opposed to the crown.[57]

Major General

[edit]Port Royal expedition

[edit]In late April, leading a fleet of seven ships and over 700 men, Phips sailed from Boston[58] to the Acadian capital, Port Royal. On May 9 he summoned Governor Louis-Alexandre des Friches de Meneval to surrender.[59] Meneval, in command of about 70 men and a fort in disrepair, promptly negotiated terms of capitulation. When Phips came ashore the next day, it was discovered that Acadians had been removing valuables, including some that were government property (and thus were supposed to come under the victor's control).[60]

Phips, whose motives continue to be debated by historians today,[Note 4] claimed this was a violation of the terms of capitulation and consequently declared the agreement void. He allowed his troops to sack the town and destroy the church, acts that he had promised to prevent in the oral surrender agreement.[61] He had the fortifications destroyed, removing all of their weaponry. Before he left, he convinced a number of Acadians to swear oaths of allegiance to the English Crown, appointed a council of locals to administer the town, and then sailed back to Boston, carrying Meneval and his garrison as prisoners of war. Phips received a hero's welcome and was lavished with praise, although he was criticized in some circles (and has been vilified in French and Acadian histories)[62] for allowing the sacking of Port Royal.[63]

Quebec expedition

[edit]

In the wake of the success, the Massachusetts provisional government agreed to organize an expedition on a larger scale against Quebec, the capital of New France, and gave its command to Phips. Originally intending to coordinate with a simultaneous overland attack on Montreal launched from Albany, New York, the expedition's departure was delayed in the vain hope that needed munitions would arrive from England. The expedition, counting 34 ships and more than 2,000 soldiers, finally sailed on August 20. It was short on ammunition, had no pilots familiar with the Saint Lawrence River, and carried what would turn out to be inadequate provisions.[64]

Because of contrary winds and the difficulty in navigating the Saint Lawrence, the expedition took eight weeks to reach Quebec.[65] The late arrival (wintry conditions were already setting in on the river) and the long voyage meant that it would be impossible to conduct a lengthy siege. Phips sent a message into the citadel demanding its surrender. Governor General Louis de Buade de Frontenac declared that his only response would be from "the mouths of my cannons".[64] Phips then held a war council, which decided to make a combined land assault and naval bombardment.[65] Both failed. The landing force, 1,200 men led by Major John Walley, were unable to cross the well-defended Saint-Charles River, and the naval bombardment failed because the New Englanders' guns were unable to reach the high battlements of the city, and they furthermore soon ran out of ammunition. The fighting, according to Phips, cost the expedition 30 deaths and one field cannon, as well as numerous wounded; disease and disaster took an additional toll. Smallpox ravaged the troops, and two transports were lost to accidents; another 200 men were lost to these causes.[66]

The expedition cost the colony £50,000 to mount, for which it issued paper currency, a first in the English colonies.[67] Many of the expedition's participants and creditors were unhappy at being paid this way, and Phips generously purchased some of the depreciated paper with hard currency, incurring financial losses in the process. At this same time, Governor Meneval petitioned for the return of minor valuables (silverware and other small items) that Phips had taken.[51] Phips was outraged when the General Council heard Meneval's case. He returned to England in February 1691 to seek support for another expedition against Quebec.[16]

Governor of Massachusetts

[edit]Soon after returning to England, Phips joined up again with Increase Mather, and again supported him in dealing with Whitehall. Increase Mather's diary says they are together on March 25, 1691, and again on March 26.[68] On March 31, they are together as Increase Mather writes a response to the Board of Trade. Also at this meeting is Sir Henry Ashurst. These three—Mather the clergyman, flanked by two knights: Sir William Phips and Sir Henry Ashurst—would emerge later as the major proponents of the various compromises that brought about a new charter. Not counting Phips, there seem to have been a total of four agents acting on behalf of Massachusetts in seeking to restore the old charter. The two agents holding official commission papers from the Massachusetts council—Cooke and Oakes—were also the least compromising and the least politically deft. The Board of Trade seems to have sought a policy of pushing through a new charter by cleaving the two knights away from these two agents. On July 24, Increase Mather recorded in his diary that he would "part with my life sooner than [compromise on charter]". Not long after this, Increase Mather left London on vacation. On August 11, 1691, a letter was written from Whitehall to King William's secretary: "I must now desire your Lordship to acquaint the King that they are willing to accept their Charter ... and no longer Insist upon the Alterations mentioned ... "[68][69] This could not have been Cooke and Oakes because they never wavered in their stance opposing a new charter. Mather's diary entry one week later (August 19) indicates that he is still either unaware or has not yet accepted this move. On August 20, the Earl of Nottingham told a committee that he had been with Sir William Phips, who informed him that the New England agents "did acquiesce therein [with the new charter]." By August 27, Increase Mather had decided to participate in the process of shaping this new charter, if reluctantly.[68]

A number of Mather's requests concerning the new charter were rejected, but William and Mary allowed Mather to nominate the colony's lieutenant governor and council members.[68] The monarchs appointed Phips as the first Royal Governor, with Increase Mather's approval, under a newly issued colonial charter for the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[68][70] The charter greatly expanded the colony's bounds, including not just the territories of the Massachusetts Bay Colony but also those of the Plymouth Colony, islands south of Cape Cod including Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket, and the present-day territories of Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.[71] It also expanded the franchise to be nearly universal (for males).[68]

Phips and Increase Mather had little in common, but they had become politically conjoined to the new charter, and it would be their job to sell it to the people of Massachusetts, who were expecting their agents to return with nothing less than the old charter restored.

Salem witch trials

[edit]Phips and Increase Mather reached Boston in separate ships on May 14, 1692. This was a Saturday afternoon, meaning all activity was to cease at sundown according to the old Puritan laws regarding the sabbath. Unlike his arrival in HMS Rose in 1683, when Phips showed little regard for the sabbath, on this occasion, Phips was highly deferential toward the theocracy. Phips's elaborate swearing-in ceremony at the meeting house was halted at sundown and delayed until the following Monday. According to one letter writer, Phips presented himself as having no intentions to oppose the ancient laws and customs of Puritan Boston. He promised to rule as a weak governor, according to the tradition of his predecessors.[72] The speech itself had likely been crafted with the care and attention of Increase Mather as they crossed the Atlantic. They seemed to have come to an agreement—you work your side of the street and I'll work mine—whereby Phips would tend to the frontier while Increase Mather and his slate of cohorts would see to domestic affairs.

Unfortunately, their crossing also coincided with the great swelling of the infamous witchcraft hysteria. More than 125 people had been arrested on charges of witchcraft and were being held in Boston and Salem prisons. On May 27, a special Court of Oyer and Terminer was created to hear the accumulated cases. This may have been Increase Mather's idea since such courts were specifically mentioned in the new charter and no one had spent more time working on the details of the charter than Increase Mather.[73] Nonetheless, Phips signed the order and may have composed it. The language of the order itself is curious because it speaks of concern for the welfare of those "imprisoned during this hot time of the year". Increase Mather's pick for lieutenant governor, William Stoughton, was chosen as chief judge of this new court.[74] There was little then to indicate that Stoughton would proceed with such ruthless conviction. Phips later claimed to have chosen nominations for the court from "persons of the best prudence and figure that could then be pitched upon",[75] and indeed, as Thomas Brattle pointed out, most were well-known and respected merchants from the Boston area.

On June 8, William Stoughton ordered a woman accused of witchcraft (Bridget Bishop) to be executed only two days later, though tradition had been to allow at least four days between order and execution. The following Monday, the clergy all around the Boston area were asked to officially weigh in on the issue. There is no official record of this meeting except what was written down by Increase Mather's son Cotton Mather and usually referred to as The Return of the Ministers, which was put into print at the end of 1692 in a book by Increase Mather, after Phips's had disrupted the trials and disbanded the Court of Oyer and Terminer. The manuscript was unknown to historians until 1943, when it was presented to archivists in a trove of documents including the infamous Letter from Cotton Mather to William Stoughton, September 2, 1692. Cotton Mather's manuscript is carefully scribed with few cross-outs or mistakes, suggesting it was not so much "minutes" of a meeting as a careful construction after the fact. It is not endorsed by any minister or government official. According to Cotton Mather's telling, the ministers at the gathering simultaneously urged both caution and speedy prosecution. Most importantly, Cotton Mather's Return does not disallow, or discredit, the admission of spectral evidence (accusations of a crime committed by one's "specter", against which there is no alibi possible). The Mathers, father and son, continued to debate this issue with other area ministers, like Samuel Willard, throughout the summer and into the fall, as documented by the minutes of the Cambridge Association.

At the end of June, five more women were condemned to die. Phips granted a reprieve to one of these but was impressed upon "by some Salem gentlemen" to take it back.[76] At this point, Phips seemed to wash his hands of the proceedings, not relishing the idea of gaining the enmity of his own lieutenant governor and powerful clergymen, including the fully committed Cotton Mather[77] and the somewhat more waffling Increase Mather. There is no record of Phips ever having traveled north to meet any of the "afflicted" or attend a single Oyer and Terminer trial or execution. Instead, Phips continued to work on recruiting troops and gathering supplies to build a fort in Maine, and he left the province around August 1 and was gone the entire month and much of September. William Stoughton seems to have officially taken over executive powers in this period of Phips's absence.[78]

French and Indian raids had resumed in the years following Phips's 1690 expeditions, so he sought to improve the province's defenses. Pursuant to his instructions from London, in 1692, he oversaw the construction of a stone fort, which was dubbed Fort William Henry, at Pemaquid (present-day Bristol, Maine), where a wooden fort had been destroyed in 1689. He recruited Major Benjamin Church to lead a 450-man expedition eventually leading to a tenuous peace agreement with the Abenaki people.[citation needed]

By the time Phips returned from Maine on September 29, 1692, twenty people had been executed and the accusations and arrests continued, including charges against many high-profile individuals, allegedly including Phips's own wife. At this point, Phips finally let it be known that the Court of Oyer and Terminer "must fall".[citation needed] A new court was formed with instructions to entirely disregard spectral evidence. But Stoughton was once again selected by his peers to be chief justice. In late January 1693, Stoughton ordered eight graves dug in advance of his next round of execution orders, not realizing that Phips would no longer appease him.[citation needed]

All eight were cleared by Phips's proclamations, leading Stoughton to storm from the court. His replacement on the court was more inclined to mercy for the accused. Beginning in February 1693, no more of the accused were condemned to die, and almost all had been released from prison by May.[citation needed]

Recall to London

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

Phips' leadership was dependent on the support of the powerful Mathers, father and son, as well as their pick to be his lieutenant governor. This strange and disparate coalition had been badly fractured by the witchcraft proceedings, and Phips' resolute and final, if slow, move to shut it down. In a letter written October 20, 1692, Cotton Mather expressed anguish over the ending of the "proceedings" and stated his displeasure with his father's recent call for presumed innocence ("Cases of Conscience"). When Phips stood up to Stoughton, he gained a terrible foe. Furthermore, Joseph Dudley, a Massachusetts native (and former Dominion official alongside Randolph) was in London, scheming to replace Phips, and in early 1693 Stoughton joined forces with him.[79]

The strain of this seems to have gotten to Phips in a way that so many previous seemingly insurmountable challenges had not. In January 1693, Phips was involved in an embarrassing and unseemly physical altercation with his subordinate captain in the royal navy, Richard Short. Their accusations against each other in letters to Whitehall[80] follow the standard lines of the Tarpaulin vs. Gentleman.[26] Short is called a drunk, corrupt, unwilling to withstand hardships, or obey direct orders. His lieutenant captain is accused of cowardice. Phips, as usual, is accused of having only a carpenter's education, poor manners, and disregarding standard procedure (reminiscent of the journal of Knepp). Phips' pick for a replacement captain, Dobbins, is accused of the same. Phips is also accused of corruption, which was a standard charge, and a standard problem for colonial leadership at this time. But Phips, having traded silver for paper after the fiasco of Quebec, and building his own ship to chase pirates in Maine, seems to take the teeth out of this accusation.

Following the Dominion government, in which Andros oversaw all of the colonies, there was a good bit of jealousy, border disputes, and jockeying for position between the new governors of the various colonies, and Phips seems to have done as much to inflame these jealousies as to work past them. Phips expressed outrage at the execution of Leisler and harbored enemies of Fletcher[51] and the New York government that replaced Leisler. Phips' ongoing struggles with Usher in New Hampshire continued as before. (In 1695, following Phips' death, Bellomont was placed over Fletcher, Usher, and Stoughton, suggesting Whitehall was unimpressed by the bickering of the three provinces and not swayed by the particular merits of any of their arguments. Bellomont ordered a posthumous pardon of Leisler.)

Keeping up the longstanding tradition of Massachusetts Bay, Phips fought against the office of custom inspectors, arguing that the port of Massachusetts did not see enough enumerated goods to warrant their presence. Instead Phips attempted to re-establish a naval office, with himself acting as head of the admiralty, thereby doling out favors to gain the support of the powerful merchant class. This was part of an old turf battle between the Admiralty and Customs, but it led to an altercation with Randolph's custom inspector, Jahleel Brenton, which seemed to follow the similar embarrassing and unseemly pattern as his altercation with Captain Short. The two altercations weighed together against Phips. Phips was accused of violating the Navigation Acts, as his predecessor had been. Blathwayt was slowly and steadily working to standardize the flow of tributes from the colonies to the Crown, and if Phips was clogging these pipes, he would need to answer for it.

By the spring elections of 1693, Phips needed new connections to balance against the dangerous enmity of Stoughton. Elisha Cooke was elected, and Phips negated his seat. For a royally appointed governor to exercise such veto power, granted only by the controversial new charter, was a highly unpopular move and could establish a dangerous precedent. Increase Mather had fought unsuccessfully to keep this veto power out of the new charter, but ironically, he seems to have been the architect of this move.[81] A few weeks later, Phips invited both men to dinner but was unable to broker a truce. Phips was still trying to maintain a bond of loyalty to Increase Mather. By many counts this move against Cooke was considered poor political calculus. The Mathers, father and son, were a house divided, trying to heal itself.[82] The Mathers had lost much credibility and public trust. Phips seemed slow to realize that Increase Mather should no longer be his trusted adviser. A year later, when Elisha Cooke was again elected, Phips allowed it to stand. But by this time, it was probably too little, too late.

On July 31, 1693, Phips hosted at his house a meeting of the General Council, including Stoughton and four other O&T judges, and read a letter that had arrived the day before from the Queen. The letter supported Phips in his ending of the trials and stated that "the greatest moderation and all due circumspection be used..[toward those accused of witchcraft]." No doubt Phips wanted the letter read into the official minutes, but by hosting the meeting at his house, one wonders if he was not trying to provoke, especially if his own wife had been among the accused.

On November 30, 1693, little over a year after Phips had shut down the Court of Oyer and Terminer, Whitehall heard complaints against Phips regarding Short and Brenton, shepherded to London by Stoughton and Dudley. A recall with the internal date of February 15, 1694, summoned Phips back to London to answer the charges. It took months for the letter to reach Boston. On July 4, 1694, Phips received the summons to appear before the Lords of Trade. Stoughton, of all people, was ordered to oversee the gathering of evidence for the hearing, a galling reversal of fortunes for Phips. Phips spent much of the summer in Maine, at Pemaquid, securing a peace treaty and overseeing the frontier defenses near his birthplace.

Phips finally sailed for England on November 17. Increase Mather was asked to go along in support but decided against it, citing the difficulty of the journey, though his diary from the time is full of yearning to return to England. They were still friendly, but it seems their coalition and partnership was in tatters.

As a final stroke, before Phips left, he pardoned all those who had been accused of witchcraft.[83] Most had already been reprieved, but a pardon ensured they would not be brought to trial in his absence. He sailed from the harbor after sunset on the sabbath, firing guns from his ship. Samuel Sewall notes the similarity to his "uncomfortable" time of arrival, but the differences are more telling. Phips was no longer sensitive to the customs of the Puritan clergy, he was loudly defying them.

Phips arrived in London in early January, 1695. Upon his arrival in London, he was arrested on exaggerated charges, levied by Dudley, that he had conspired to withhold customs monies. Phips was bailed out by Sir Henry Ashurst but fell ill with a fever[citation needed] and died on February 18, 1695,[2] aged 44, before his charges were heard. He was buried in London at the Church of St. Mary Woolnoth.

Family and legacy

[edit]William and Mary Phips had no children. They adopted Spencer Bennett, the son of Mary's sister Rebecca,[84] who formally took the Phips name in 1716.[85] He went on to serve as Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, including two periods as acting governor.[86]

Phippsburg, Maine, is named in his honor.[87][88]

Notes

[edit]- ^ All dates are Julian calendar, as recorded at the time, except that each new year is begun on January 1 (as opposed to March 25). Orthography is also updated for clarity.

- ^ Ann Jacobsen's biography of Blathwayt also points to this.

- ^ Letters of Randolph are now freely available online in various forms and can usually arranged by date.

- ^ Griffiths (2005), p. 151 provides several competing points of view on the matter.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lounsberry (1941), pp. 8–11

- ^ a b Chu (2000)

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), p. 10

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), p. 5

- ^ Calef, Robert (1700). More Wonders of the Invisible World. Public Domain: Nathaniel Hillar at the Prince's Arms. pp. Postscript, 145.

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), p. 21

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 16

- ^ a b Baker & Reid (1998), p. 15

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), p. 16

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), p. 17

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 22

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 23

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), pp. 24–26

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), pp. 26–27

- ^ Earle, Peter (1979). The Treasure of the Concepcion. New York: The Viking Press. p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e Diary of Samuel Sewall" Vol. I 1674–1700, Vol II 1700–1729 MHS Collections Vol. V-VI Fifth Series, Boston MA 1878. Public Domain. Happy wife is June, 1688. Golden Fleece is July, 1688. Becoming free in 1691 and bold emphasis is mine.

- ^ Earle (1979) p. 125. Earle's citation is from the Archivo General de Indias, Seville.

- ^ Peter Earle (1979) pp. 122–125.

- ^ a b Randolph to Sir Leoline Jenkins July 26, 1683, in British History Online

- ^ Karraker, Cyrus H. (1932-10-01). "The Treasure Expedition of Captain William Phips to the Bahama Banks". The New England Quarterly. 5 (4): 731–752. doi:10.2307/359331. JSTOR 359331.

- ^ a b c Murdock, Kenneth B. (1925). Increase Mather. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 152–154.

- ^ Washburn, Emory (1840). Sketches of the Judicial History of Massachusetts. Boston, MA: Little and Brown. Public Domain. p. 121.

- ^ "[Randolph] clamored for a ship, preferably a ship of war to give the business prestige."Michael G. Hall Edward Randolph and the American Colonies (1960) pp. 79–81.

- ^ Eward Randolph to Sir Leoline Jenkins, British History Online, August 3,1683.

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998) p. 30

- ^ a b c Davies, J.D. (1991). Gentlemen and Tarpaulins: The Officers and Men of the Restoration Navy. New York: Oxford. pp. 16–21 passim.

- ^ a b c MHS holds a copy of John Knepp Journal in the F.L. Gay Collection. It remains unpublished but is available for public viewing in their reading room.

- ^ a b John Knepp at MHS & F.L. Gay "A Rough List of a Collection of Transcripts"

- ^ a b Baker & Reid (1998), p. 32

- ^ Diary by Increase Mather. 1674–1687. Cambridge MA. University Press. 1900. p. 51 or search by date.

- ^ British History online search Blathwayt and July 1683.

- ^ Davies (1991) p. 64

- ^ Hall (1960), See index under "Rose" or "Phips"

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 85

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), pp. 41–43

- ^ Earle, Peter (1979) p. 154

- ^ Earle (1979) p. 158

- ^ Earle (1979) p. 160-167

- ^ Earle (1979) p. 165-7

- ^ Fine (2006), pp. 48–52

- ^ Earle (1979) p. 181

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 140

- ^ Earle (1979) p. 201

- ^ a b Baker & Reid (1998), p. 54

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 147

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), pp. 55–58

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), pp. 59–63

- ^ Diary of Increase Mather (MHS & AAS). August 1688 entry contains I.M.'s first mention of Phips, as the two of them begin working together on behalf of Massachusetts in London. They would continue to work together for the next 4 years. Also see F.L. Gay, ''Rough List of the Collection" available online.

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), pp. 69–74

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 200

- ^ a b c Barnes, Viola F. (1928-07-01). "The Rise of William Phips". The New England Quarterly. 1 (3): 271–294. doi:10.2307/359875. JSTOR 359875.

- ^ Griffiths (2005), p. 190

- ^ Calef, Robert (1700). More Wonders of the Invisible World. London: Public Domain. Online. BPL. pp. see postscript regarding Cotton Mather's "Life of Phips".

- ^ Pietas in Patriam. Life of His Excellency Sir William Phips. Dedicated to the Earl of Bellomont. London 1697. Anonymously published but later owned by Cotton Mather and included in his Magnalia.

- ^ See Upham Vol I and II for detailed descriptions of Parris admitting new members.

- ^ Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series of the reign of William and Mary. Vol I-III. Preserved in the Public Record Office (PRO). London. Available online. Sir Francis speaks of need for masts is July 1692. For Blathwayt on Phips christening see March 6, 1691.

- ^ British History online, 1691, search Blathwayt and "baptised"

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 210

- ^ Faragher (2005), p. 87

- ^ Griffiths (2005), p. 151

- ^ Faragher (2005), p. 88

- ^ See e.g. Faragher (2005), p. 88

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 213

- ^ a b "Biography of Sir William Phips". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- ^ a b Peckham (1964), p. 36

- ^ Peckham (1964), p. 37

- ^ Peckham (1964), p. 38

- ^ a b c d e f The Glorious Revolution in Massachusetts, Selected Documents 1689–1692, pp. 544–624. The documents are in chronological order.

- ^ Baker & Reid (1998), pp. 206–210

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 245

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 252

- ^ Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies, London, 1901. Now also found online at British History online. Letter-writer is Joshua Broadbent, June 21, 1692.

- ^ Moody, Robert Earle, ed. (1988). The Glorious Revolution in Massachusetts 1689–1692. Virginia: Colonial Society of Massachusetts. p. 612 Note: some activités of Phips are omitted but the industriousness of Increase Mather is very well-documented.

- ^ Hart (1927), 2: 41

- ^ Calendar of State Papers (1901) and British History online, see October 12, 1692.

- ^ Calef, Robert (1700) Public Domain, many editions available with different pagination. Search for Rebecca Nurse.

- ^ See 1692 private letters from Cotton Mather to various correspondents August 5, September 2, September 22, and October 20.

- ^ Moore, George H. (1888). Bibliographical Notes on Witchcraft in Massachusetts. Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, Public Domain. p. 9: Moore lists Phips as having been present at General Council (not O&T) meetings on June 13, 18; July 4, 8, 15, 18, 21–22, 25–26; September 5, 12, 16; October 14, 22, 26.

- ^ Kimball (1911), p. 66

- ^ Calendar (1901) and British History online. See February 15, 1693, for Phips's account. Other accounts, including Captain Short's, follow thereafter.

- ^ Sewall DI, Vol I. See June 8, 1693: "Mr. Danforth labors to bring Mr. Mather and Cooke together. Is great wrath about Mr. Cooke's being refused and tis supposed Mr. [Increase] Mather is the cause."

- ^ See Increase Mather's postscript to "Cases of Conscience", which was added around this time as a reprint in London and tagged to the end of his son's "Wonder's of the Invisible World".

- ^ Calef, Robert (1700)

- ^ Lounsberry (1941), p. 284

- ^ Paige (1877), 2: 627

- ^ Williamson (1832), pp. 260, 327

- ^ Williamson (1832), p. 637

- ^ Chadbourne, Ava H. (Apr 20, 1949). "Many Maine towns bear names of military men". Lewiston Evening Journal. pp. A-2. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, Emerson W.; Reid, John G. (1998). The New England Knight: Sir William Phips, 1651–1695. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-0925-8. OCLC 222435560.

- Chu, Jonathan M. (2000). "Phips, Sir William (1651-1695), first royal governor of Massachusetts". American National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0100728. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Earle, Peter (1980). The Treasure of the Concepción: The Wreck of the Almiranta. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-72558-7.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3. OCLC 217980421.

- Fine, John Christopher (2006). Treasures of the Spanish Main. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-1-59228-760-4. OCLC 70265588.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- Hall, Michael Garibaldi (1960). Edward Randolph and the American Colonies. University of North Carolina Press.

- Hart, Albert Bushnell, ed. (1927). Commonwealth History of Massachusetts. New York: The States History Company. OCLC 1543273.

- Kimball, Everett (1911). The Public Life of Joseph Dudley. New York: Longmans, Green. OCLC 1876620.

- Lounsberry, Alice (1941). Sir William Phips. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 3040370.

- Paige, Lucius (1877). History of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Boston: H. O. Houghton. p. 627. OCLC 1305589.

- Peckham, Howard (1964). The Colonial Wars, 1689–1762. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 1175484.

- Rawlyk, George (1973). Nova Scotia's Massachusetts. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0142-3. OCLC 1371993.

- Williamson, William (1832). The History of the State of Maine. Hallowell, ME: Glazier, Masters. OCLC 193830.

External links

[edit]- Profile, law2.umkc.edu; accessed December 23, 2014.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne on Phips in the collection "Memoir of Nathaniel Hawthorne with Stories ... " (Public Domain).