Republic of Burundi | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

| Anthem: "Burundi Bwacu" (Kirundi) "Our Burundi" | |

Location of Burundi (dark blue)

in Africa (light blue) | |

| Capital | 3°30′S 30°00′E / 3.500°S 30.000°E |

| Largest city | Bujumbura |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2020)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Burundian |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic under an authoritarian dictatorship[2][3] |

| Évariste Ndayishimiye[4] | |

| Nestor Ntahontuye | |

| Prosper Bazombanza | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| National Assembly | |

| Establishment history | |

| 1680–1966 | |

• Part of German East Africa | 1890–1916 |

• Part of Ruanda-Urundi | 1916–1962 |

• Independence from Belgium | 1 July 1962 |

• Republic | 28 November 1966 |

| 17 May 2018 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 27,834 km2 (10,747 sq mi)[7] (142nd) |

• Water (%) | 10[6] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 14,151,540 [8] (78th) |

• Density | 473/km2 (1,225.1/sq mi) (25th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2023) | low (187th) |

| Currency | Burundian franc (FBu) (BIF) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Calling code | +257 |

| ISO 3166 code | BI |

| Internet TLD | .bi |

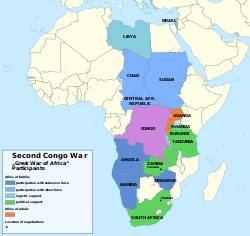

Burundi,[b] officially the Republic of Burundi,[c] is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is located in the Great Rift Valley at the junction between the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa, with a population of over 14 million people.[16] It is bordered by Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east and southeast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west; Lake Tanganyika lies along its southwestern border. The political capital city is Gitega and the economic capital city is Bujumbura.[17]

The Twa, Hutu and Tutsi peoples have lived in Burundi for at least 500 years. For more than 200 of those years, Burundi was an independent kingdom. In 1885, it became part of the German colony of German East Africa.[18] After the First World War and Germany's defeat, the League of Nations mandated the territories of Burundi and neighboring Rwanda to Belgium in a combined territory called Rwanda-Urundi. After the Second World War, this transformed into a United Nations Trust Territory. Burundi gained independence in 1962 and initially retained the monarchy. However, a coup d'état in 1966 replaced the monarchy with a one-party republic, and for the next 27 years, Burundi was ruled by a series of ethnic Tutsi dictators and notably experienced a genocide of its Hutu population in 1972. In July 1993, Melchior Ndadaye became Burundi's first Hutu president following the country's first multi-party presidential election. His assassination three months later during a coup attempt provoked the 12-year Burundian Civil War. In 2000, the Arusha Agreement was adopted, which was largely integrated in a new constitution in 2005. Since the 2005 post-war elections, the country's dominant party has been the Hutu-led National Council for the Defense of Democracy – Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD–FDD), widely accused of authoritarian governance and perpetuating the country's poor human rights record.

Burundi remains primarily a rural society, with just 13.4% of the population living in urban areas in 2019.[19] Burundi is densely populated, and many young people emigrate in search of opportunities elsewhere. Roughly 81% of the population are of Hutu ethnic origin, 18% are Tutsi, and fewer than 1% are Twa.[20] The official languages of Burundi are Kirundi, French, and English—Kirundi being officially recognised as the sole national language.[21] English was made an official language in 2014.[22]

One of the smallest countries in Africa, Burundi's land is used mostly for subsistence agriculture and grazing. Deforestation, soil erosion, and habitat loss are major ecological concerns.[23] As of 2005[update], the country was almost completely deforested. Less than 6% of its land was covered by trees, with over half of that being for commercial plantations.[24] Burundi is the poorest country in the world by nominal GDP per capita and is one of the least developed countries. It faces widespread poverty, corruption, instability, authoritarianism and illiteracy. The 2018 World Happiness Report ranked the country as the world's least happy with a rank of 156.[25] Burundi is a member of the African Union, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, United Nations, East African Community (EAC), OIF and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Etymology

[edit]Modern Burundi is named after the King of Urundi, who ruled the region starting in the 16th century. It derives its name from a word "Urundi" in Kirundi the local language, which means "Another one".[citation needed] Later the Belgian mandate to Ruanda-Urundi region came to rename it and their former capital "Usumbura" of both kingdoms by adding the letter "B" in front of it.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Burundi is one of the few countries in Africa, along with its neighbour Rwanda among others (such as Botswana, Lesotho, and Eswatini), to be a direct territorial continuation of a pre-colonial era African state. The early history of Burundi, and especially the role and nature of the country's three dominant ethnic groups, the Twa, Hutu and Tutsi, is highly debated amongst academics.[26]

Kingdom of Burundi

[edit]The first evidence of the Burundian state dates back to the late 16th century where it emerged on the eastern foothills. Over the following centuries it expanded, annexing smaller neighbours. The Kingdom of Burundi or Urundi, in the Great Lakes region was a polity ruled by a traditional monarch with several princes beneath him; succession struggles were common.[5] The king, known as the mwami (translated as ruler) headed a princely aristocracy (ganwa) which owned most of the land and required a tribute, or tax, from local farmers (mainly Hutu) and herders (mainly Tutsi). The Kingdom of Burundi was characterised by a hierarchical political authority and tributary economic exchange.[27]

In the mid-18th century, the Tutsi royalty consolidated authority over land, production, and distribution with the development of the ubugabire—a patron-client relationship in which the populace received royal protection in exchange for tribute and land tenure. By this time, the royal court was made up of the Tutsi-Banyaruguru. They had higher social status than other pastoralists such as the Tutsi-Hima. In the lower levels of this society were generally Hutu people, and at the very bottom of the pyramid were the Twa. The system had some fluidity, however. Some Hutu people belonged to the nobility and in this way also had a say in the functioning of the state.[28]

The classification of Hutu or Tutsi was not merely based on ethnic criteria alone. Hutu farmers that managed to acquire wealth and livestock were regularly granted the higher social status of Tutsi, some even made it to become close advisors of the Ganwa. On the other hand, there are also reports of Tutsi that lost all their cattle and subsequently lost their higher status and were called Hutu. Thus, the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was also a socio-cultural concept, instead of a purely ethnic one.[29][30] There were also many reports of marriages between Hutu and Tutsi people.[31] In general, regional ties and power struggles played a far more determining role in Burundi's politics than ethnicity.[30]

Rule by Germany and Belgium

[edit]From 1884, the German East Africa Company was active in the African Great Lakes region. As a result of heightened tensions and border disputes between the German East Africa Company, the British Empire and the Sultanate of Zanzibar, the German Empire was called upon to put down the Abushiri revolts and protect the empire's interests in the region. The German East Africa Company transferred its rights to the German Empire in 1891, in this way establishing the German colony of German East Africa, which included Burundi (Urundi), Rwanda (Ruanda), and the mainland part of Tanzania (formerly known as Tanganyika).[32] The German Empire stationed armed forces in Rwanda and Burundi during the late 1880s. The location of the present-day city of Gitega served as an administrative centre for the Ruanda-Urundi region.[33]

During the First World War, the East African Campaign greatly affected the African Great Lakes region. The Belgian and British colonial forces of the allied powers launched a coordinated attack on the German colony. The German army stationed in Burundi was forced to retreat by the numerical superiority of the Belgian army and by 17 June 1916, Burundi and Rwanda were occupied. The Force Publique and the British Lake Force then started a thrust to capture Tabora, an administrative centre of central German East Africa. After the war, as outlined in the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was forced to cede "control" of the Western section of the former German East Africa to Belgium.[34][35]

On 20 October 1924, Ruanda-Urundi, which consisted of modern-day Rwanda and Burundi, became a Belgian League of Nations mandate territory, with Usumbura as its capital. In practical terms it was considered part of the Belgian colonial empire. Burundi, as part of Ruanda-Urundi, continued its kingship dynasty despite the presence of European authorities.[19][36]

The Belgians, however, preserved many of the kingdom's institutions; the Burundian monarchy succeeded in surviving into the post-colonial period.[5] Following the Second World War, Ruanda-Urundi was classified as a United Nations Trust Territory under Belgian administrative authority.[19] During the 1940s, a series of policies caused divisions throughout the country. On 4 October 1943, powers were split in the legislative division of Burundi's government between chiefdoms and lower chiefdoms. Chiefdoms were in charge of land, and lower sub-chiefdoms were established. Native authorities also had powers.[36] In 1948, Belgium allowed the region to form political parties.[34] These factions contributed to Burundi gaining its independence from Belgium, on 1 July 1962.

Independence

[edit]

On 20 January 1959, King Mwami Mwambutsa IV requested Burundi's independence from Belgium and dissolution of the Ruanda-Urundi union.[37] In the following months, Burundian political parties began to advocate for the end of Belgian colonial rule and the separation of Rwanda and Burundi.[37] The first and largest of these political parties was the Union for National Progress (UPRONA).

Burundi's push for independence was influenced by the Rwandan Revolution and the accompanying instability and ethnic conflict that occurred there. As a result of the Rwandan Revolution, many Rwandan Tutsi refugees arrived in Burundi from 1959 to 1961.[38][39][40]

Burundi's first elections took place on 8 September 1961 and UPRONA, a multi-ethnic unity party led by Prince Louis Rwagasore won just over 80% of the electorate's votes. In the wake of the elections, on 13 October, the 29-year-old Prince Rwagasore was assassinated, robbing Burundi of its most popular and well-known nationalist.[34][41]

The country claimed independence on 1 July 1962,[34] and legally changed its name from Ruanda-Urundi to Burundi.[42] Burundi became a constitutional monarchy with Mwami Mwambutsa IV, Prince Rwagasore's father, serving as the country's king.[39] On 18 September 1962 Burundi joined the United Nations.[43]

In 1963, King Mwambutsa appointed a Hutu prime minister, Pierre Ngendandumwe, but he was assassinated on 15 January 1965 by a Rwandan Tutsi employed by the US Embassy. The assassination occurred in the broader context of the Congo Crisis during which Western anti-communist countries were confronting the communist People's Republic of China as it attempted to make Burundi a logistics base for communist insurgents battling in Congo.[44] Parliamentary elections in May 1965 brought a majority of Hutu into the parliament, but when King Mwambutsa appointed a Tutsi prime minister, some Hutu felt this was unjust and ethnic tensions were further increased. In October 1965, an attempted coup d'état led by the Hutu-dominated police was carried out but failed. The Tutsi dominated army, then led by Tutsi officer Captain Michel Micombero[39] purged Hutu from their ranks and carried out reprisal attacks which ultimately claimed the lives of up to 5,000 people in a precursor to the 1972 Burundian Genocide.[45]

King Mwambutsa, who had fled the country during the October coup of 1965, was deposed by a coup in July 1966 and his teenage son, Prince Ntare V, claimed the throne. In November that same year, the Tutsi Prime Minister, then-Captain Michel Micombero, carried out another coup, this time deposing Ntare, abolishing the monarchy and declaring the nation a republic, though his one-party government was effectively a military dictatorship.[34] As president, Micombero became an advocate of African socialism and received support from the People's Republic of China. He imposed a staunch regime of law and order and sharply repressed Hutu militarism.

Civil war and genocides

[edit]In late April 1972, two events led to the outbreak of the First Burundian Genocide. On 27 April 1972, a rebellion led by Hutu members of the gendarmerie broke out in the lakeside towns of Rumonge and Nyanza-Lac and the rebels declared the short-lived Martyazo Republic.[46][47] The rebels attacked both Tutsi and any Hutu who refused to join their rebellion.[48][49] During this initial Hutu outbreak, anywhere from 800 to 1200 people were killed.[50] At the same time, King Ntare V of Burundi returned from exile, heightening political tension in the country. On 29 April 1972, the 24-year-old Ntare V was murdered. In subsequent months, the Tutsi-dominated government of Michel Micombero used the army to combat Hutu rebels and commit genocide, murdering targeted members of the Hutu majority. The total number of casualties was never established, but contemporary estimates put the number of people killed between 80,000 and 210,000.[51][52] In addition, several hundred thousand Hutu were estimated to have fled the killings into Zaïre, Rwanda and Tanzania.[52][53]

Following the civil war and genocide, Micombero became mentally distraught and withdrawn. In 1976, Colonel Jean-Baptiste Bagaza, a Tutsi, led a bloodless coup to topple Micombero and set about promoting reform. His administration drafted a new constitution in 1981, which maintained Burundi's status as a one-party state.[39] In August 1984, Bagaza was elected head of state. During his tenure, Bagaza suppressed political opponents and religious freedoms.

Major Pierre Buyoya, a Tutsi, overthrew Bagaza in 1987, suspended the constitution and dissolved political parties. He reinstated military rule by a Military Committee for National Salvation (CSMN).[39] Anti-Tutsi ethnic propaganda disseminated by the remnants of the 1972 UBU, which had re-organized as PALIPEHUTU in 1981, led to killings of Tutsi peasants in the northern communes of Ntega and Marangara in August 1988. The government put the death toll at 5,000,[citation needed] some international NGOs[who?] believed this understated the deaths.

The new regime did not unleash the harsh reprisals of 1972. Its effort to gain public trust was eroded when it decreed an amnesty for those who had called for, carried out, and taken credit for the killings. Analysts have called this period the beginning of the "culture of impunity." Other analysts put the origins of the "culture of impunity" earlier, in 1965 and 1972, when a small number of identifiable Hutus unleashed massive killings of Tutsis.[citation needed]

In the aftermath of the killings, a group of Hutu intellectuals wrote an open letter to Pierre Buyoya, asking for more representation of the Hutu in the administration. They were arrested and jailed. A few weeks later, Buyoya appointed a new government, with an equal number of Hutu and Tutsi ministers. He appointed Adrien Sibomana (Hutu) as Prime Minister. Buyoya also created a commission to address issues of national unity.[39] In 1992, the government created a new constitution that provided for a multi-party system,[39] but a civil war broke out.

An estimated total of 250,000 people died in Burundi from the various conflicts between 1962 and 1993.[54]

Since Burundi's independence in 1962, two genocides have taken place in the country: the 1972 mass killings of Hutus by the Tutsi-dominated army,[55] and the mass killings of Tutsis in 1993 by the Hutu majority. Both were described as genocides in the final report of the International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi presented in 2002 to the United Nations Security Council.[56]

First attempt at democracy and war between Tutsi National Army and Hutu population

[edit]In June 1993, Melchior Ndadaye, leader of the Hutu-dominated Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU), won the first democratic election. He became the first Hutu head of state, leading a pro-Hutu government. Though he attempted to smooth the country's bitter ethnic divide, his reforms antagonised soldiers in the Tutsi-dominated army, and he was assassinated amidst a failed military coup in October 1993, after only three months in office. The ensuing Burundian Civil War (1993–2005) saw persistent violence between Hutu rebels and the Tutsi majority army. It is estimated that some 300,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed in the years following the assassination.[57]

In early 1994, the parliament elected Cyprien Ntaryamira (Hutu) to the office of president. He and Juvénal Habyarimana, the president of Rwanda, both Hutus, died together when their airplane was shot down in April 1994. More refugees started fleeing to Rwanda. Speaker of Parliament, Sylvestre Ntibantunganya (Hutu), was appointed as president in October 1994. A coalition government involving 12 of the 13 parties was formed. A feared general massacre was averted, but violence broke out. A number of Hutu refugees in Bujumbura,[citation needed] the then-capital, were killed. The mainly Tutsi Union for National Progress withdrew from the government and parliament.

In 1996, Pierre Buyoya (Tutsi) again took power through a coup d'état. He suspended the constitution and was sworn in as president in 1998. This was the start of his second term as president, after his first term from 1987 to 1993. In response to rebel attacks, the government forced much of the population to move to refugee camps.[citation needed] Under Buyoya's rule, long peace talks started, mediated by South Africa. Both parties signed agreements in Arusha, Tanzania and Pretoria, South Africa, to share power in Burundi. The agreements took four years to plan.

On 28 August 2000, a transitional government for Burundi was planned as a part of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement. The transitional government was placed on a trial basis for five years. After several aborted cease-fires, a 2001 peace plan and power-sharing agreement has been relatively successful. A cease-fire was signed in 2003 between the Tutsi-controlled Burundian government and the largest Hutu rebel group, CNDD-FDD (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy).[58]

In 2003, FRODEBU leader Domitien Ndayizeye (Hutu) was elected president.[citation needed] In early 2005, ethnic quotas were formed for determining positions in Burundi's government. Throughout the year, elections for parliament and president occurred.[59]

Pierre Nkurunziza (Hutu), once a leader of a rebel group, was elected president in 2005. As of 2008[update], the Burundian government was talking with the Hutu-led Palipehutu-National Liberation Forces (NLF)[60] to bring peace to the country.[61]

Peace agreements

[edit]African leaders began a series of peace talks between the warring factions following a request by the United Nations Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali for them to intervene in the humanitarian crisis. Talks were initiated under the aegis of former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere in 1995; following his death, South African President Nelson Mandela took the helm. As the talks progressed, South African President Thabo Mbeki and United States President Bill Clinton also lent their respective weight.

The main objective was to transform the Burundian government and military structurally in order to bridge the ethnic gap between the Tutsi and Hutu. It was to take place in two major steps. First, a transitional power-sharing government would be established, with the presidents holding office for three-year terms. The second objective involved a restructuring of the armed forces, where the two groups would be represented equally.[62]

As the protracted nature of the peace talks demonstrated, the mediators and negotiating parties confronted several obstacles. First, the Burundian officials perceived the goals as "unrealistic" and viewed the treaty as ambiguous, contradictory and confusing. Second, and perhaps most importantly, the Burundians believed the treaty would be irrelevant without an accompanying cease fire. This would require separate and direct talks with the rebel groups. The main Hutu party was skeptical of the offer of a power-sharing government; they alleged that they had been deceived by the Tutsi in past agreements.

In 2000,[63] the Burundian President signed the treaty, as well as 13 of the 19 warring Hutu and Tutsi factions. Disagreements persisted over which group would preside over the nascent government, and when the ceasefire would begin. The spoilers of the peace talks were the hardliner Tutsi and Hutu groups who refused to sign the accord; as a result, violence intensified. Three years later at a summit of African leaders in Tanzania, the Burundian president and the main opposition Hutu group signed an accord to end the conflict; the signatory members were granted ministerial posts within the government. However, smaller militant Hutu groups – such as the Forces for National Liberation – remained active.[64]

UN involvement

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Between 1993 and 2003, many rounds of peace talks, overseen by regional leaders in Tanzania, South Africa and Uganda, gradually established power-sharing agreements to satisfy the majority of the contending groups. Initially the South African Protection Support Detachment was deployed to protect Burundian leaders returning from exile. These forces became part of the African Union Mission to Burundi, deployed to help oversee the installation of a transitional government. In June 2004, the UN stepped in and took over peacekeeping responsibilities as a signal of growing international support for the already markedly advanced peace process in Burundi.[65]

The mission's mandate, under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, has been to monitor cease-fire, carry out disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of former military personnel, support humanitarian assistance and refugee and IDP return, assist with elections, protect international staff and Burundian civilians, monitor Burundi's troublesome borders, including halting illicit arms flows, and assist in carrying out institutional reforms including those of the Constitution, judiciary, armed forces and police. The mission has been allotted 5,650 military personnel, 120 civilian police and about 1,000 international and local civilian personnel. The mission has been functioning well. It has greatly benefited from the transitional government, which has functioned and is in the process of transitioning to one that will be popularly elected.[65]

The main difficulty in the early stages was continued resistance to the peace process by the last Hutu nationalist rebel group. This organisation continued its violent conflict on the outskirts of the capital despite the UN's presence. By June 2005, the group had stopped fighting and its representatives were brought back into the political process. All political parties have accepted a formula for inter-ethnic power-sharing: no political party can gain access to government offices unless it is ethnically integrated.[65]

The focus of the UN's mission had been to enshrine the power-sharing arrangements in a popularly voted constitution, so that elections may be held and a new government installed. Disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration were done in tandem with elections preparations. In February 2005, the constitution was approved with over 90% of the popular vote. In May, June and August 2005, three separate elections were also held at the local level for the Parliament and the presidency.

While there are still some difficulties with refugee returns and securing adequate food supplies for the war-weary population, the mission managed to win the trust and confidence of a majority of the formerly warring leaders, as well as the population at large.[65] It was involved with several "quick effect" projects, including rehabilitating and building schools, orphanages, health clinics and rebuilding infrastructure such as water lines.

The 2005 Constitution formalised a complex power-sharing architecture that has been described as "associational" in its logic, as it aims to provide guarantees of representation for the Tutsi minority without entrenching the ethnic cleavage at the centre of Burundian politics.[66] This institutional design provides an original contribution from Burundian negotiators and constitution makers to institutional options to manage ethnic conflict.[citation needed]

2006 to 2018

[edit]

Reconstruction efforts in Burundi started to practically take effect after 2006. The UN shut down its peacekeeping mission and re-focused on helping with reconstruction.[67] Toward achieving economic reconstruction, Rwanda, D.R.Congo and Burundi relaunched the regional Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries.[67] In addition, Burundi, along with Rwanda, joined the East African Community in 2007.

However, the terms of the September 2006 Ceasefire between the government and the last remaining armed opposition group, the FLN (Forces for National Liberation, also called NLF or FROLINA), were not totally implemented, and senior FLN members subsequently left the truce monitoring team, claiming that their security was threatened.[68] In September 2007, rival FLN factions clashed in the capital, killing 20 fighters and causing residents to begin fleeing. Rebel raids were reported in other parts of the country.[67] The rebel factions disagreed with the government over disarmament and the release of political prisoners.[69] In late 2007 and early 2008, FLN combatants attacked government-protected camps where former combatants were living. The homes of rural residents were also pillaged.[69]

The 2007 report[69] of Amnesty International mentions many areas where improvement is required. Civilians are victims of repeated acts of violence done by the FLN. The latter also recruits child soldiers. The rate of violence against women is high. Perpetrators regularly escape prosecution and punishment by the state. There is an urgent need for reform of the judicial system. Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity continued to go unpunished.[citation needed]

In late March 2008, the FLN sought for the parliament to adopt a law guaranteeing them 'provisional immunity' from arrest. This would cover ordinary crimes, but not grave violations of international humanitarian law like war crimes or crimes against humanity .[69] Even though the government has granted this in the past to people, the FLN has been unable to obtain the provisional immunity.

On 17 April 2008, the FLN bombarded Bujumbura. The Burundian army fought back and the FLN suffered heavy losses. A new ceasefire was signed on 26 May 2008. In August 2008, President Nkurunziza met with the FLN leader Agathon Rwasa, with the mediation of Charles Nqakula, South Africa's Minister for Safety and Security. This was the first direct meeting since June 2007. Both agreed to meet twice a week to establish a commission to resolve any disputes that might arise during the peace negotiations.[70]

The UN has attempted to evaluate the impact of its peace-building initiatives. In the early 2010s, the UN peacekeeping mission in Burundi sought to assess the success of its Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration program by counting the number of arms that had been collected, given the prevalence of arms in the country. However, these evaluations failed to include data from local populations, which are significant in impact evaluations of peacebuilding initiatives.[71]

As of 2012, Burundi was participating in African Union peacekeeping missions, including the mission to Somalia against Al-Shabaab militants.[72] In 2014, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established, initially for four years and then extended for another four in 2018.[73][74]

2015 unrest

[edit]In April 2015 protests broke out after the ruling party announced President Pierre Nkurunziza would seek a third term in office.[75] Protestors claimed Nkurunziza could not run for a third term in office but the country's constitutional court agreed with Nkurunziza (although some of its members had fled the country at the time of its vote).[76]

An attempted coup d'état on 13 May failed to depose Nkurunziza. [77] [78] He returned to Burundi, began purging his government, and arrested several of the coup leaders.[79][80][81][82][83] Following the attempted coup, however, protests continued; over 100,000 people had fled the country by 20 May, causing a humanitarian emergency. There are reports of continued and widespread abuses of human rights, including unlawful killings, torture, disappearances, and restrictions on freedom of expression.[84][85]

Despite calls by the United Nations, the African Union, the United States, France, South Africa, Belgium, and various other governments to refrain, the ruling party held parliamentary elections on 29 June, but these were boycotted by the opposition.

On 30 September 2016, the United Nations Human Rights Council established the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi through resolution 33/24. Its mandate is to "conduct a thorough investigation into human rights violations and abuses committed in Burundi since April 2015, to identify alleged perpetrators and to formulate recommendations."[86] On 29 September 2017 the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi called on Burundian government to put an end to serious human rights violations. It further stressed that, "The Burundian government has so far refused to cooperate with the Commission of Inquiry, despite the Commission's repeated requests and initiatives."[87] The violations the Commission documented include arbitrary arrests and detentions, acts of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, rape and other forms of sexual violence."[87]

2018 to present

[edit]

In a constitutional referendum in May 2018, Burundians voted by 79.08% to approve an amended constitution that ensured that Nkurunziza could remain in power until 2034.[88][89] However, much to the surprise of most observers, Nkurunziza later announced that he did not intend to serve another term, paving the way for a new president to be elected in the 2020 general election.[90]

On 20 May 2020, Evariste Ndayishimiye, a candidate who was hand-picked as Nkurunziza's successor by the CNDD-FDD, won the election with 71.45% of the vote.[91] Shortly after, on 9 June 2020, Nkurunziza died of a cardiac arrest, at the age of 55.[90] There was some speculation that his death was COVID-19 related, though this is unconfirmed.[92] As per the constitution, Pascal Nyabenda, the president of the national assembly, led the government until Ndayishimiye's inauguration on 18 June 2020.[90][91]

In December 2021, a large prison fire killed dozens in the capital city of Gitega.[93]

In November 2022, in challenges to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Burundi's economic growth increased slightly to 3 percent, according to an assessment of the International Monetary Fund.

Currently, Burundi remains as one of the poorest nations on Earth based on a Gross National Income (GNI) of $270 per capita.[94]

The fall of Goma in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in January 2025 was the largest escalation of the conflict in Kivu since 2012 and raised concerns that the Rwandan-backed M23 rebel campaign could turn into a larger regional war due to the presence of troops from Rwanda and Burundi in the Kivu provinces. Thousands of soldiers had been deployed to assist the Congolese army in South Kivu by Burundi, which has a Hutu-dominated government and previously accused Rwanda of backing a 2015 coup attempt, adding to concern for the potential of a larger regional war.[95][96]

Government

[edit]

Burundi's political system is that of a presidential representative democratic republic based upon a multi-party state. The president of Burundi is the head of state and head of government. There are currently 21 registered parties in Burundi.[34] On 13 March 1992, Tutsi coup leader Pierre Buyoya established a constitution,[97] which provided for a multi-party political process and reflected multi-party competition.[98] Six years later, on 6 June 1998, the constitution was changed, broadening National Assembly's seats and making provisions for two vice-presidents. Because of the Arusha Accord, Burundi enacted a transitional government in 2000.[99]

Burundi's legislative branch is a bicameral assembly, consisting of the Transitional National Assembly and the Transitional Senate. As of 2004[update], the Transitional National Assembly consisted of 170 members, with the Front for Democracy in Burundi holding 38% of seats, and 10% of the assembly controlled by UPRONA. Fifty-two seats were controlled by other parties. Burundi's constitution mandates representation in the Transitional National Assembly to be consistent with 60% Hutu, 40% Tutsi, and 30% female members, as well as three Batwa members.[34] Members of the National Assembly are elected by popular vote and serve five-year terms.[100]

The Transitional Senate has fifty-one members, and three seats are reserved for former presidents. Due to stipulations in Burundi's constitution, 30% of Senate members must be female. Members of the Senate are elected by electoral colleges, which consist of members from each of Burundi's provinces and communes.[34] For each of Burundi's eighteen provinces, one Hutu and one Tutsi senator are chosen. One term for the Transitional Senate is five years.[100]

Together, Burundi's legislative branch elect the president to a five-year term.[100] Burundi's president appoints officials to his Council of Ministers, which is also part of the executive branch.[99] The president can also pick fourteen members of the Transitional Senate to serve on the Council of Ministers.[34] Members of the Council of Ministers must be approved by two-thirds of Burundi's legislature. The president also chooses two vice-presidents.[100] Following the 2015 election, the president of Burundi was Pierre Nkurunziza. The first vice-president was Therence Sinunguruza, and the Second Vice-president was Gervais Rufyikiri.[101]

On 20 May 2020, Evariste Ndayishimiye, a candidate who was hand-picked as Nkurunziza's successor by the CNDD-FDD, won the election with 71.45% of the vote. Shortly after, on 9 June 2020, Nkurunziza died of a cardiac arrest, at the age of 55. As per the constitution, Pascal Nyabenda, the president of the national assembly, led the government until Ndayishimiye's inauguration on 18 June 2020.[102][103]

The Cour Suprême (Supreme Court) is Burundi's highest court. There are three Courts of Appeals directly below the Supreme Court. Tribunals of First Instance are used as judicial courts in each of Burundi's provinces as well as 123 local tribunals.[99]

Censorship

[edit]Burundi's government has been repeatedly criticised for the multiple arrests and trials of journalist Jean-Claude Kavumbagu for issues related to his reporting.[104] Amnesty International (AI) named him a prisoner of conscience and called for his "immediate and unconditional release."

Human rights

[edit]In April 2009, the government of Burundi changed the law to criminalise homosexuality. Persons found guilty of consensual same-sex relations risk three months to two years in prison and/or a fine of 50,000 to 100,000 Burundian francs.[105] Amnesty International has condemned the action, calling it a violation of Burundi's obligations under international and regional human rights law, and against the constitution, which guarantees the right to privacy.[106]

Burundi officially left the International Criminal Court (ICC) on 27 October 2017, the first country in the world to do so.[107] The move came after the UN accused the country of various crimes and human rights violations, such as extrajudicial killings, torture and sexual violence, in a September 2017 report.[107] The ICC announced on 9 November 2017 that human rights violations from the time Burundi was a member would still be prosecuted.[108][109]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Burundi's provinces and communes were created on Christmas Day in 1959 by a Belgian colonial decree. They replaced the pre-existing system of chieftains.[110]

In 2000, the province encompassing Bujumbura was separated into two provinces, Bujumbura Rural and Bujumbura Mairie.[111] In 2015, the province of Rumonge was created from portions of Bujumbura Rural and Bururi.[112] From 2015 to 2025, Burundi was divided into eighteen provinces,[113] 119 communes,[34] and 2,638 collines (hills).[114]

In July 2022, the government of Burundi announced a complete overhaul of the country's territorial subdivisions. The proposed change would reduce the number of provinces from eighteen to five, and the communes from 119 to 42. The change was approved by both the National Assembly and the Senate and took effect with the parliamentary elections in July 2025.[110][115]

With the new administrative division, the country is now made up of five provinces: Buhumuza, Bujumbura, Burunga, Butanyerera and Gitega. These provinces are further subdivided into 42 communes, 451 zones and 3044 collines and quartiers.[116]

Geography

[edit]

One of the smallest countries in Africa, Burundi is landlocked and has an equatorial climate. Burundi is a part of the Albertine Rift, the western extension of the East African Rift. The country lies on a rolling plateau in the centre of Africa. Burundi is bordered by Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east and southeast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west. It lies within the Albertine Rift montane forests, Central Zambezian miombo woodlands, and Victoria Basin forest-savanna mosaic ecoregions.[117]

The average elevation of the central plateau is 1,707 m (5,600 ft), with lower elevations at the borders. The highest peak, Mount Heha at 2,685 m (8,810 ft),[118] lies to the southeast of the largest city and economic capital, Bujumbura. The source of the Nile River is in Bururi province, and is linked from Lake Victoria to its headwaters via the Ruvyironza River.[119][clarification needed] Lake Victoria is also an important water source, which serves as a fork to the Kagera River.[120][121] Another major lake is Lake Tanganyika, located in much of Burundi's southwestern corner.[122]

In Burundi forest cover is around 11% of the total land area, equivalent to 279,640 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, up from 276,480 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 166,670 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 112,970 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 23% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 41% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.[123][124]

There are two national parks: Kibira National Park to the northwest (a small region of rainforest, adjacent to Nyungwe Forest National Park in Rwanda), and Ruvubu National Park to the northeast (along the Rurubu River, also known as Ruvubu or Ruvuvu). Both were established in 1982 to conserve wildlife populations.[125]

Wildlife

[edit]Economy

[edit]

Burundi is a landlocked, resource-poor country with an underdeveloped manufacturing sector. The economy is predominantly agricultural, accounting for 50% of GDP in 2017[126] and employing more than 90% of the population. Subsistence agriculture accounts for 90% of agriculture.[127] Burundi's primary exports are coffee and tea, which account for 90% of foreign exchange earnings, though exports are a relatively small share of GDP. Other agricultural products include cotton, tea, maize, sorghum, sweet potatoes, bananas, manioc (tapioca); beef, milk and hides. Even though subsistence farming is highly relied upon, many people do not have the resources to sustain themselves. This is due to large population growth and no coherent policies governing land ownership. In 2014, the average farm size was about one acre.

Burundi is one of the world's poorest countries, owing in part to its landlocked geography,[19] lack of access to education and the proliferation of HIV/AIDS. Approximately 80% of Burundi's population lives in poverty.[128] Famines and food shortages have occurred throughout Burundi, most notably in the 20th century,[36] and according to the World Food Programme, 56.8% of children under age five suffer from chronic malnutrition.[129] Burundi's export earnings – and its ability to pay for imports – rests primarily on weather conditions and international coffee and tea prices.

The purchasing power of most Burundians has decreased as wage increases have not kept up with inflation. As a result of deepening poverty, Burundi will remain heavily dependent on aid from bilateral and multilateral donors. Foreign aid represents 42% of Burundi's national income, the second highest rate in Sub-Saharan Africa. Burundi joined the East African Community in 2009, which should boost its regional trade ties, and also in 2009 received $700 million in debt relief. Government corruption is hindering the development of a healthy private sector as companies seek to navigate an environment with ever-changing rules.[19]

Studies since 2007 have shown Burundians to have extremely poor levels of satisfaction with life; the World Happiness Report 2018 rated them the world's least happy.[25][130]

Some of Burundi's natural resources include uranium, nickel, cobalt, copper and platinum.[131] Besides agriculture, other industries include: the assembly of imported components; public works construction; food processing, and light consumer goods such as blankets, shoes, and soap.

In regards to telecommunications infrastructure, Burundi is ranked second to last in the World Economic Forum's Network Readiness Index (NRI) – an indicator for determining the development level of a country's information and communication technologies. Burundi ranked number 147 overall in the 2014 NRI ranking, down from 144 in 2013.[132]

Lack of access to financial services is a serious problem for the majority of the population, particularly in densely populated rural areas: only 2% of the total population holds bank accounts and fewer than 0.5% use bank lending services. Microfinance, however, plays a larger role, with 4% of Burundians being members of microfinance institutions – a larger share of the population than that reached by banking and postal services combined. 26 licensed microfinance institutions (MFIs) offer savings, deposits, and short- to medium-term credit. The dependence of the sector on donor assistance is limited.[133]

Burundi is part of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation. Burundi economy has declined since 1990s and Burundi is behind all neighbouring countries.

Burundi was ranked 127th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[134]

Currency

[edit]Burundi's currency is the Burundian franc. It is nominally subdivided into 100 centimes, though coins have never been issued in centimes in independent Burundi; centime coins were circulated only when Burundi used the Belgian Congo franc.

Monetary policy is controlled by the central bank, Bank of the Republic of Burundi.

| Current BIF exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD |

Transport

[edit]

Burundi's transport network is limited and underdeveloped. According to a 2012 DHL Global Connectedness Index, Burundi is the least globalised of 140 surveyed countries.[135] Bujumbura International Airport is the only airport with a paved runway and as of May 2017 it was serviced by four airlines (Brussels Airlines, Ethiopian Airlines, Kenya Airways and RwandAir). Kigali is the city with the most daily flight connections to Bujumbura. The country has a road network but as of 2005[update] less than 10% of the country's roads were paved and as of 2012[update] private bus companies were the main operators of buses on the international route to Kigali; however, there were no bus connections to the other neighbouring countries (Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo).[136] Bujumbura is connected by a passenger and cargo ferry (the MV Mwongozo) to Kigoma in Tanzania.[137] There is a long-term plan to link the country via rail to Kigali and then onward to Kampala and Kenya.

Demographics

[edit]| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bujumbura | Bujumbura Mairie | 374,809 | ||||||

| 2 | Gitega | Gitega | 135,467 | ||||||

| 3 | Ngozi | Ngozi | 39,884 | ||||||

| 4 | Rumonge | Bururi | 35,931 | ||||||

| 5 | Cibitoke | Cibitoke | 23,885 | ||||||

| 6 | Kayanza | Kayanza | 21,767 | ||||||

| 7 | Bubanza | Bubanza | 20,031 | ||||||

| 8 | Karuzi | Karuzi | 10,705 | ||||||

| 9 | Kirundo | Kirundo | 10,024 | ||||||

| 10 | Muyinga | Muyinga | 9,609 | ||||||

As of October 2021, Burundi was estimated by the United Nations to have a population of 12,346,893,[139][140] compared to only 2,456,000 in 1950.[141] The population growth rate is 2.5 percent per year, more than double the average global pace, and a Burundian woman has on average 5.10 children, more than double the international fertility rate.[142] Burundi had the tenth highest total fertility rate in the world, just behind Somalia, in 2021.[19]

Many Burundians have migrated to other countries as a result of the civil war. In 2006, the United States accepted approximately 10,000 Burundian refugees.[143]

Burundi remains an overwhelmingly rural society, with just 13% of the population living in urban areas in 2013.[19] The population density of around 315 people per square kilometre (753 per sq mi) is the second highest in Sub-Saharan Africa.[34] Roughly 85% of the population are of Hutu ethnic origin, 15% are Tutsi and fewer than 1% are indigenous Twa.[20] Non-Africans in Burundi include approximately 3,000 Europeans and 2,000 South Asians.[144]

Languages

[edit]The official languages of Burundi are Kirundi, French, and English. English was made an official language in 2014.[22] Virtually the entire population speaks Kirundi, and just under 10% speak French.[145]

Religion

[edit]Sources estimate the Christian population at 80–90%, with Roman Catholics representing the largest group at 60–65%. Protestant and Anglican practitioners constitute the remaining 15–25%. An estimated 5% of the population adheres to traditional indigenous religious beliefs. Muslims constitute 2–5%, the majority of whom are Sunnis and live in urban areas.[19][146][147]

Health

[edit]Burundi has the worst hunger and malnourishment rates of all 120 countries ranked in the Global Hunger Index.[142] The civil war in 1962 put a stop on the medical advancements in the country.[148] Burundi, again, went into a violent cycle in 2015, jeopardising the citizens of Burundi's medical care.[149] Like other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Burundi uses indigenous medicine in addition to biomedicine. In the 1980s, Burundi's health authorities asked the United Nations Development Program for support to develop quality control for and begin new research on pharmaceuticals from medicinal plants.[148] At the same time, the Burundi Association of Traditional Practitioners (ATRADIBU) was founded, which teamed up with the governments agency to set up the Centre for Research and Promotion of Traditional Medicine in Burundi (CRPMT).[148] The recent influx of international aid has supported the work of biomedical health systems in Burundi. However, international aid workers have traditionally stayed away from indigenous medicine in Burundi.[148] As of 2015, roughly 1 out of 10 children in Burundi die before the age of 5 from preventable and treatable illnesses such as pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria.[149] The current violence in Burundi has limited the country's access to medication and hospital equipment. The life expectancy in Burundi, as of 2015, was 60.1 years.[150] In 2013, Burundi spent 8% of their GDP on healthcare.[150] While Burundi's fertility rate is 6.1 children per women, the country's infant death rate is 61.9 deaths for every 1,000 live births.[150] Common diseases in Burundi include malaria and typhoid fever.[150]

Culture

[edit]

Burundi's culture is based on local tradition and the influence of neighbouring countries, though cultural prominence has been hindered by civil unrest. Since farming is the main industry, a typical Burundian meal consists of sweet potatoes, corn, rice and peas. Due to the expense, meat is eaten only a few times per month.

When several Burundians of close acquaintance meet for a gathering they drink impeke, a beer, together from a large container to symbolise unity.[151]

Notable Burundians include: the footballers Mohamed Tchité, Gaël Bigirimana, Youssouf Ndayishimiye; the professor of Economics Léonce Ndikumana, the philanthropist Deogratias Niyizonkiza, the writer and model Esther Kamatari, the humanitarian activist Marguerite Barankitse, the journalist and chief editor Antoine Kaburahe and the singer Jean-Pierre Nimbona, popularly known as Kidumu (who is based in Nairobi, Kenya).

Crafts are an important art form in Burundi and are attractive gifts to many tourists. Basket weaving is a popular craft for local artisans,[152] as well as other crafts such as masks, shields, statues and pottery.[153]

Drumming is an important part of the cultural heritage. The world-famous Royal Drummers of Burundi, who have performed for over 40 years, are noted for traditional drumming using the karyenda, amashako, ibishikiso and ikiranya drums.[154] Dance often accompanies drumming performance, which is frequently seen in celebrations and family gatherings. The abatimbo, which is performed at official ceremonies and rituals and the fast-paced abanyagasimbo are some famous Burundian dances. Some musical instruments of note are the flute, zither, ikembe, indonongo, umuduri, inanga and the inyagara.[153]

The country's oral tradition is strong, relaying history and life lessons through storytelling, poetry and song. Imigani, indirimbo, amazina and ivyivugo are literary genres in Burundi.[155]

Basketball and track and field are noted sports. Martial arts are popular, as well. There are five major judo clubs: Club Judo de l'Entente Sportive, in Downtown, and four others throughout the city.[156] Association football is a popular pastime throughout the country, as are mancala games.

Most Christian holidays are celebrated, with Christmas being the largest.[157] Burundian Independence Day is celebrated annually on 1 July.[158] In 2005, the Burundian government declared Eid al-Fitr, an Islamic holiday, to be a public holiday.[159]

Media

[edit]Education

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (June 2018) |

In 2012, the adult literacy rate in Burundi was estimated to be 74.71% for men and women between the ages of 15 and 24, while the youth literacy rate was much higher at 92.58%.[160] Burundi has a comparatively high literacy rate to other countries in the region, which is only about 10% lower than the global average.[160] Ten percent of Burundian boys are allowed a secondary education.[161]

Burundi has one public university, University of Burundi. There are museums in the cities, such as the Burundi Geological Museum in Bujumbura and the Burundi National Museum and the Burundi Museum of Life in Gitega.

In 2010 a new elementary school was opened in the small village of Rwoga that is funded by the pupils of Westwood High School, Quebec, Canada.[162][163]

As of 2022, Burundi invested the equivalent of 5% of its GDP in education.[160]

Science and technology

[edit]Burundi's Strategic Plan for Science, Technology, Research and Innovation (2013) covers the following areas: food technology; medical sciences; energy, mining and transportation; water; desertification; environmental biotechnology and indigenous knowledge; materials science; engineering and industry; ICTs; space sciences; mathematical sciences; and social and human sciences.

With regard to material sciences, Burundi's publication intensity doubled from 0.6 to 1.2 articles per million inhabitants between 2012 and 2019, placing it in the top 15 for sub-Saharan Africa for this strategic technology.[164]

Medical sciences remain the main focus of research: medical researchers accounted for 4% of the country's scientists in 2018 but 41% of scientific publications between 2011 and 2019.[164]

The focus of the Strategic Plan for Science, Technology, Research and Innovation (2013) has been on developing an institutional framework and infrastructure, fostering greater regional and international co-operation and placing science in society. In October 2014, the EAC Secretariat designated the National Institute of Public Health a centre of excellence. Data are unavailable on output on nutritional sciences, the institute's area of specialization, but between 2011 and 2019, Burundi scientists produced seven articles on each of HIV and tropical communicable diseases and a further five on tuberculosis, all focus areas for the Sustainable Development Goals.[164]

The Strategic Plan has also focused on training researchers. Researcher density (in head counts) grew from 40 to 55 researchers per million inhabitants between 2011 and 2018. The amount of funding available to each researcher more than doubled from PPP$14,310 (constant 2005 values) to PPP$22,480, since the domestic research effort has also risen since 2012, from 0.11% to 0.21% of GDP.[164]

Burundi has almost tripled its scientific output since 2011 but the pace has not picked up since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. With six scientific publications per million inhabitants, Burundi still has one of the lowest publication rate in Central and East Africa.[164] Some 97.5% of publications involved foreign co-authorship between 2017 and 2019, with Ugandans figuring among the top five partners.[164]

See also

[edit]- Outline of Burundi

- Culture of Burundi

- Wildlife of Burundi

- National Defence Force (Burundi)

- Anti-clerical campaign of the government of Burundi

Notes

[edit]- ^ Including ~3,000 Europeans and ~2,000 South Asians

- ^ /bəˈrʊndi/ ⓘ bə-RUUN-dee or /bəˈrʌndi/ bə-RUN-dee

- ^ Kirundi: Repuburika y’Uburundi[15] [u.βu.ɾǔː.ndi]; Swahili: Jamuhuri ya Burundi [ɓuˈruⁿdi] ⓘ; French: République du Burundi [buʁundi, byʁyndi]

References

[edit]- ^ "National Profiles". Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Inside the most brutal dictatorship you've never heard of". British GQ. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024.

- ^ Féron, Élise (14 November 2023). "'Throwing in my two cents': Burundian diaspora youth between conventional and transformative forms of mobilization". Globalizations. 22 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1080/14747731.2023.2282256. ISSN 1474-7731.

- ^ "Burundi's ruling party wins presidential election". Reuters. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Kingdom of Burundi". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Annuaire statistique du Burundi (PDF) (Report) (in French). ISTEEBU. July 2015. p. 105. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ "Quelques données pour le Burundi" (in French). ISTEEBU. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ "Burundi Population (2024) - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Bank Open Data".

- ^ "Human Development Report 2025" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 6 May 2025. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2025. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ "Constitution de la République du Burundi promulguée le 07 juin 2018". 3 July 2018. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Burundi Population (2024) - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ "Loi n°1/04 du 04 février 2019 portant Fixation de la Capitale Politique et de la Capitale Economique du Burundi". 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Strizek, Helmut (2006). Geschenkte Kolonien: Ruanda und Burundi unter deutscher Herrschaft [Donated colonies: Rwanda and Burundi under German rule]. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3861533900.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Burundi", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 31 January 2024, archived from the original on 22 January 2021, retrieved 5 February 2024

- ^ a b Eggers, p. ix.

- ^ Maurer, Sous la direction de Bruno (1 October 2016). Les approches bi-plurilingues d'enseignement-apprentissage: autour du programme Écoles et langues nationales en Afrique (ELAN-Afrique): Actes du colloque du 26–27 mars 2015, Université Paul-Valéry, Montpellier, France. Archives contemporaines. ISBN 9782813001955. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Burundi: l'anglais officialisé aux côtés du français et du kirundi". RFI (in French). 29 August 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Bermingham, Eldredge, Dick, Christopher W. and Moritz, Craig (2005). Tropical Rainforests: Past, Present, and Future. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, p. 146. ISBN 0-226-04468-8

- ^ Butler, Rhett A. (2006). "Burundi". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 5 May 2006.

- ^ a b Collinson, Patrick (14 March 2018). "Finland is the happiest country in the world, says UN report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Uvin, Peter. 1999. "Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence" in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr. 1999), pp. 253–272 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 254.

- ^ VANDEGINSTE, S., Stones left unturned: law and transitional justice in Burundi, Antwerp-Oxford-Portland, Intersentia, 2010, p 17.

- ^ R. O. Collins & J. M. Burns. 2007. A History of Sub-Saharan Africa, Cambridge University Press. Page 125.

- ^ Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (2003). The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-1-890951-34-4.

- ^ a b WEISSMAN, S., Preventing genocide in Burundi: lessons from international diplomacy, Washington D.C., United States Institute of Peace Press, 1998, p5.

- ^ "Burundi". 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "German East Africa | former German dependency, Africa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

In archived text: German East Africa, German Deutsch-Ostafrika, former dependency of imperial Germany, corresponding to present-day Rwanda and Burundi, the continental portion of Tanzania, and a small section of Mozambique. Penetration of the area was begun in 1884 by German commercial agents, and German claims were recognized by the other European powers in the period 1885–94. In 1891 the German imperial government took over administration of the area from the German East Africa Company. Although its subjugation was not completed until 1907, the colony experienced considerable economic development before World War I. During the war it was occupied by the British, who received a mandate to administer the greater part of it (Tanganyika Territory) by the Treaty of Versailles (signed June 1919; enacted January 1920). A smaller portion (Ruanda-Urundi) was entrusted to Belgium.

- ^ "Gitega | Burundi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Background Note: Burundi Archived 22 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine. United States Department of State. February 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- ^ a b c Weinstein, Warren; Robert Schrere (1976). Political Conflict and Ethnic Strategies: A Case Study of Burundi. Syracuse University: Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. p. 5. ISBN 0-915984-20-2.

- ^ a b Weinstein, Warren; Robert Schrere (1976). Political Conflict and Ethnic Strategies: A Case Study of Burundi. Syracuse University: Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. p. 7. ISBN 0-915984-20-2.

- ^ MacDonald, Fiona; et al. (2001). Peoples of Africa. Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 60. ISBN 0-7614-7158-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Timeline: Burundi". BBC News. 25 February 2010. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Timeline: Rwanda Archived 26 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Amnesty International. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ^ "Ethnicity and Burundi’s Refugees" Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, African Studies Quarterly: The online journal for African Studies. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ^ Cook, Chris; Diccon Bewes (1999). What Happened Where: A Guide to Places and Events in Twentieth-Century. London, England: Routledge. p. 281. ISBN 1-85728-533-6.

- ^ United Nations Member States Archived 1 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. 3 July 2006. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- ^ Lemarchand (1996), pp. 17, 21

- ^ Burundi (1993–2006) Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. University of Massachusetts Amherst

- ^ Lemarchand (1996), p. 89 Archived 18 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lemarchand, (2008). Section "B – Decision-Makers, Organizers and Actors"

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S.; Charny, Israel W. (2004). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Psychology Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-415-94430-4. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Manirakiza, Marc (1992) Burundi : de la révolution au régionalisme, 1966–1976, Le Mât de Misaine, Bruxelles, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Lemarchand, (2008). Section "B – Decision-Makers, Organizers and Actors" cites (Chrétien Jean-Pierre and Dupaquier, Jean-Francois, 2007, Burundi 1972: Au bord des génocides, Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 106)

- ^ White, Matthew. Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century: C. Burundi (1972–73, primarily Hutu killed by Tutsi) 120,000 Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi (2002). Paragraph 85. "The Micombero regime responded with a genocidal repression that is estimated to have caused over a hundred thousand victims and forced several hundred thousand Hutus into exile"

- ^ Longman, Timothy Paul (1998). Proxy Targets: Civilians in the War in Burundi. Human Rights Watch. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-56432-179-4.

- ^ Hagget, Peter. Encyclopedia of World Geography. Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish, 2002. ISBN 0-7614-7306-8.

- ^ Past genocides, Burundi resources Archived 25 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine on the website of Prevent Genocide International

lists the following resources:

- Michael Bowen, Passing By;: The United States and Genocide in Burundi, 1972, (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1973), 49 pp.

- René Lemarchand, Selective genocide in Burundi (Report – Minority Rights Group; no. 20, 1974), 36 pp.

- Lemarchand (1996)

- Edward L. Nyankanzi, Genocide: Rwanda and Burundi (Schenkman Books, 1998), 198 pp.

- Christian P. Scherrer, Genocide and crisis in Central Africa : conflict roots, mass violence, and regional war; foreword by Robert Melson. Westport, Conn. : Praeger, 2002.

- Weissman, Stephen R."Preventing Genocide in Burundi Lessons from International Diplomacy". Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link),

- ^ International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi (2002). Paragraphs 85,496.

- ^ Country profile Burundi BBC. Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (accessed on 29 October 2008)

- ^ Global Ceasefire Agreement between Burundi and the CNDD-FDD Archived 14 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 20 November 2003. Relief Web. United Nations Security Council. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ "Burundi: Basic Education Indicators" (PDF). Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) UNESCO. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 22 June 2008. - ^ Haskin, Jeanne M. (2005) The Tragic State of the Congo: From Decolonization to Dictatorship. New York, NY: Algora Publishing, ISBN 0-87586-416-3 p. 151.

- ^ Liang, Yin (4 June 2008). "EU welcomes positive developments in Burundi" Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. China View. Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ^ Raffoul, Alexandre (2019). "Tackling the power-sharing dilemma? The role of mediation" (PDF). Swisspeace: 1–59. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Jan van Eck – peace mediator in Burundi". Radio Netherlands Archives. 7 August 2000. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Ndayiragije, Alexandre W. Raffoul and Réginas (11 May 2020). "Burundi: Power-sharing (Dis)agreements". 50 Shades of Federalism. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Howard, Lise Morje (2008). UN Peacekeeping in Civil Wars. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Raffoul, Alexandre W. (1 January 2020). "The Politics of Association: Power-Sharing and the Depoliticization of Ethnicity in Post-War Burundi". Ethnopolitics. 19 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/17449057.2018.1519933. ISSN 1744-9057. S2CID 149937031. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Timeline Burundi BBC. Archived 30 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (accessed on 29 October 2008)

- ^ "Burundi". Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Amnesty International - ^ a b c d Burundi: Release Civilians Detained Without Charge |Human Rights Watch Archived 2 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Hrw.org (29 May 2008). Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Peace Building Commission Update, A project of the Institute for Global Policy Archived 19 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 2008

- ^ Autesserre, Séverine; Gbowee, Leymah (3 May 2021). The Frontlines of Peace: An Insider's Guide to Changing the World (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197530351.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-753035-1. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Explosion rocks Somali parliament – Africa Archived 6 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Al Jazeera English (7 November 2012). Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Nduwimana, Patrick (18 April 2014). "Burundi creates reconciliation body that divides public opinion". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Rugiririz, Ephrem (25 November 2019). "Burundi: the commission of divided truths". JusticeInfo.net. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Après moi, moi". The Economist. 2 May 2015. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "Burundi court backs President Nkurunziza on third-term" Archived 20 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- ^ "Mind the coup". The Economist. 13 May 2015. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Gun clashes rage on in Burundi as radio station attacked". nation.co.ke. 14 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "Burundi's president returns to divided capital after failed coup" Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian (15 May 2015). Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Burundi general declares coup against President Nkurunziza" Archived 11 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- ^ Burundi arrests leaders of attempted coup Archived 16 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. CNN.com (15 May 2015). Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Laing, Aislinn. (15 May 2015) "Burundi president hunts for coup leaders as he returns to the capital" Archived 30 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "President 'back in Burundi' after army says coup failed" Archived 5 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Al Jazeera English (15 May 2015). Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Burundi 2015/6" Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Amnesty International. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "We feel forgotten" Archived 17 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian. Retrieved 10 April 2016

- ^ "OHCHR – Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Burundi". www.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ a b "OHCHR – Commission calls on Burundian government to put an end to serious human rights violations". www.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ Moore, Jina (17 May 2018). "In Tiny Burundi, a Huge Vote (Published 2018)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Amendments to constitution of Burundi approved: electoral commission – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Dahir, Abdi Latif (9 June 2020). "President of Burundi, Pierre Nkurunziza, 55, Dies of Heart Attack". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Who is Burundi's new president, Evariste Ndayishimiye?". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Burke, Jason (9 June 2020). "Burundi president dies of illness suspected to be coronavirus". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Burundi prison fire kills at least 38 in Gitega". BBC News. 7 December 2021. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ Santosdiaz, Richie (19 August 2022). "Burundi: Fintech Landscape and Potential In The World's Poorest Country". The Fintech Times. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Lewis, David; Rolley, Sonia (31 January 2025). "M23 rebels face Burundian forces in eastern Congo, heightening war fears". Reuters. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Africa File Special Edition: M23 March Threatens Expanded Conflict in DR Congo and Regional War in the Great Lakes". Institute for the Study of War. 31 January 2025. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ "Burundi". Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) International Center for Transitional Justice. Retrieved 27 July 2008. - ^ "Burundi – Politics". Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) From "The Financial Times World Desk Reference". Dorling Kindersley. 2004. Prentice Hall. Retrieved 30 June 2008. - ^ a b c "Republic of Burundi: Public Administration Country Profile" (PDF). United Nations' Division for Public Administration and Development Management: 5–7. July 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d Puddington, Arch (2007). Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Syracuse University: Lanham, Maryland. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-7425-5897-7.

- ^ Burundi – World Leaders Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. CIA. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Dahir, Abdi Latif (9 June 2020). "President of Burundi, Pierre Nkurunziza, 55, Dies of Heart Attack". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Who is Burundi's new president, Evariste Ndayishimiye?". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Burundi: Free Journalist Detained on Treason Charges". Human Rights Watch. 20 July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ Burundi abolishes the death penalty but bans homosexuality Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Amnesty International. 27 April 2009.

- ^ a b Moore, Jina (27 October 2017). "Burundi Quits International Criminal Court". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick; Simons, Marlise (9 November 2017). "We're Not Done Yet, Hague Court Tells Burundi's Leaders". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "ICC: New Burundi Investigation". Human Rights Watch. 9 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ a b bdiagnews (14 July 2022). "Burundi : Proposition – 5 provinces au lieu de 18 et 42 communes au lieu de 119". Nouvelles du Burundi – Africa Generation News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Eggers, p. xlix.

- ^ Nkurunziza, Pierre (26 March 2015). "LOI No 1/10 DU 26 MARS 2015 PORTANT CREATION DE LA PROVINCE DU RUMONGE ET DELIMITATION DES PROVINCES DE BUJUMBURA, BURURI ET RUMONGE" (PDF). Presidential Cabinet, Republic of Burundi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Law, Gwillim. "Provinces of Burundi". Statoids. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Kavamahanga, D.D, Kavamahanga (11 July 2004). "Empowerment of people living with HIV/AIDS in Gitega Province, Burundi". Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) International Conference on AIDS 2004. 15 July 2004. NLM Gateway. Retrieved 22 June 2008. - ^ "Why Burundi will only have 5 provinces instead of 18?". RegionWeek. 11 January 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "Loi Organique N° 1/05 du 16 Mars 2023 portant détermination et délimitation des Provinces, des Communes, des Zones, des Collines et/ou Quartiers de la République du Burundi". CENI Burundi. 16 March 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ O'Mara, Michael (1999). Facts about the World's Nations. Bronx, New York: H.W. Wilson, p. 150, ISBN 0-8242-0955-9

- ^ Ash, Russell (2006). The Top 10 of Everything. New York City: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0-600-61557-X

- ^ Klohn, Wulf and Mihailo Andjelic. Lake Victoria: A Case in International Cooperation Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 20 July 2008.